During the beginning of trench warfare on the Western Front in the fall and winter of 1914, German snipers took a large toll on British and French soldiers. The Germans had access to scoped rifles and better tactics at the time than the Allies, yet the later gradually caught up as World War I progressed. By the later half of the war, the British had developed proper scoped rifles, schools and tactics specifically for snipers.

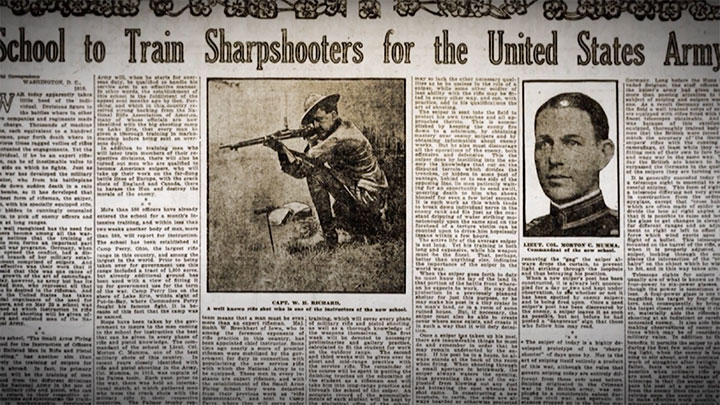

When the United States entered the war in 1917, the lessons and tactics offered by the experienced British blended well with the marksmanship training already drilled into American soldiers, especially those who would become snipers on the front. The National Rifle Association had a large role in this preparation, as Camp Perry became the largest and most formal sniper school in the nation in 1918, known as the small arms training school.

The camp's senior officers for the program were all officials of the National Rifle Association, decorated and accomplished Olympic-level shooters who either had National Guard or no military background. Also at Camp Perry at the time were five sniper instructors, including H. W. McBride, who wrote A Rifleman Went To War.

Prior to World War I, the U.S. adopted the box-shaped Warner & Swazey M1913 Musket Scope to be mounted onto the M1903 Springfield rifle in a sharpshooter role. The M1913 Musket Sight mounted offset on the left side of the M1903 receiver and had a rubberized eye piece to eliminate glare and prevent the back of the optic from hitting the user's eye. While the rifles they were mounted to were capable, the optics themselves could be problematic and difficult to adjust in combat.

The Marine Corps had a more practical optic put into use on the M1903 in the from of the Winchester A5 tubular-telescopic sights mounted directly over the centerline of the bore similar to most optics used today. The Marines used the M1903 and Winchester A5 pair in combat during the war, but it is not fully know what effect they had in comparison to the Warner & Swazey M1913.

Trench Guns

With the need for additional arms in 1917, especially ones geared for the natures of trench warfare, the United States turned to the use of combat shotguns. This was not a new concept, as shotguns had been used in the decades prior during the Philippine-American War. The model most used was the Winchester M1897 tube-fed, pump-action shotgun chambered in 12 ga., though the hammerless Winchester Model 12 and Remington Model 10 were also used.

The shotguns were modified to include a shorter barrel, ventilated barrel shroud and bayonet lug. The rapid-fire capability coupled with the shot pattern of the shotguns made for an ideal weapon to assault and clear out enemy troops within the close-quarters of a trench. The M1897 and other militarized shotguns earned the unofficial nickname of 'trench gun' which stuck. The trench guns were initially used with paper shells, which tended to swell in the moist conditions of the trenches and fail to feed. This problem was remedied by switching to full brass shells.

The trench guns became a source of controversy when in September 1918, the German government sent an ultimatum to the U.S. Secretary of State decrying their use by American soldiers as barbarism. This was an ironic and silly complaint coming from the nation to introduce the use of poison gas and unrestricted submarine warfare during World War I. The Germans stated that any American soldier caught with a trench gun or related ammunition would be executed.

It is not well known or agreed upon on how many of these trench shotguns were used in actual combat. This is furthered by the fact that there is a lack of photos of American frontline soldiers using trench guns, which is interesting since the U.S. Army Signal Corps photographed a lot of the equipment used in France at that time. This could be due to the German complaint against the use of trench guns, and seems that an order was given at some level not to photograph them.

Lest We Forget

The Meuse-Argonne offensive started in September 1918 as the final push against German forces on the Western Front, and would ultimately help force the end of the war. The largest concentration of American soldiers and Marines would take part in the offensive, including the future general George S. Patton, who lead an armored brigade and was injured early in the part of the offensive.

By this point in the war, the United States had two new machine guns at its disposal from the brilliant inventor John Moses Browning, the M1917 and the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle. The M1917 is a water-cooled, belt-fed machine gun that is recoil operated and chambered in .30-'06 Sprg. used on a stationary tripod mount similar to the British Vickers. The M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle is an air-cooled, gas operated select-fire rifle chambered in .30-'06 Sprg. fed by 20-round detachable box magazines.

The M1917 and M1918 were sent to U.S. troops in the final month of the war to replace the earlier American and foreign made machine guns being used up to that point. The BAR did not include a bipod at the time, as it was intended to be used as a suppressive automatic rifle in a method called "walking fire." The 36th Infantry Division of the Texas National Guard and 2nd Infantry Division were issued the M1918 BAR at that time.

U.S. Marines also acquired a few M1918 BARs and request more to replace the French CSRG Chauchat machine guns they were using, though the guns would not be available to them until the last day of the war. On Nov. 8, 1918 two train cars pulled alongside containing delegates from the Allied nations and Imperial Germany. Over the next three days, the delegates worked out the details for an armistice to end the war.

By 5 a.m. on Nov. 11 an agreement was reached and signed. A cease fire was scheduled for the eleventh minute, of the eleventh hour, of the eleventh day of Nov. 1918, what would become known as Armistice Day. Despite the cease fire, men like Pvt. Albert A. Beavers of the 2nd Infantry Division were killed just before the time was reached on Nov. 11 and the guns fell silent. And so ended the fighting of World War I, a conflict which had lasted 228 weeks, caused 38 million casualties and changed the world forever.

After the armistice came the Treaty of Versailles, which harshly punished and put the debt of war reparations on Germany. The terms of this treaty would ultimately cause the conditions for the rise of Nazi Germany and a new world war 20 years later. Today, the site where the armistice was signed in the rail car is marked by a memorial commemorating the end of hostilities on Nov. 11, 1918.

To watch complete segments of past episodes of American Rifleman TV, go to americanrifleman.org/artv. For all-new episodes of ARTV, tune in Wednesday nights to Outdoor Channel 8:30 p.m. and 11:30 p.m. EST.