During World War I, 30,582 M1917 Brownings—including this gun serving with the U.S. Army’s 83rd Division near Mayet—were sent to France, but only 1,168 saw combat before Nov. 11, 1918.

The first practical self-loading machine gun was developed in the mid-1880s by a self-taught American engineer, Hiram Maxim. His recoil-operated, belt-fed gun fired at a rate of approximately 600 rounds per minute. It soon gained a great deal of success, and many nations—chiefly in Europe—adopted the Maxim, or variants thereof, around the turn of the 20th century.

The legendary inventor John Moses Browning began work on an air-cooled, recoil-operated machine gun of his own design, which resulted in the introduction of the Model 1895. The U.S. military procured a limited number of the Model 1895 Browning machine guns—also known as Colt’s Automatic Gun or the “potato digger”—in several calibers for the U.S. Army and Navy. Nonetheless, for various reasons, the American military establishment never fully embraced the machine gun. Even so, limited numbers of several types of machine guns and automatic rifles were procured between 1904 and 1915, including the Model 1904 Hotchkiss, Model 1909 Benét-Mercié, Model 1915 Vickers and the Lewis Gun. Total production of these guns was relatively nominal, and few were in our military’s inventory at the outbreak of the Great War in 1914.

Along with artillery, the belt-fed, water-cooled, tripod-mounted machine gun was responsible for much of the carnage that was inflicted on all sides on the Western Front during the war. The initial engagements produced horrendous casualties when 19th century tactics of massed infantry charges went up against 20th century technology of rapid-fire machine guns ensconced in fixed defensive positions. Eventually, the war devolved into static trench warfare with both sides being protected by machine guns. The wholesale slaughter occurring in France was one of the reasons for the strong isolationist sentiment in the United States. However, by the end of 1916, it was apparent to all but the most myopic that America would eventually be drawn into the conflict.

When the United States formally declared war in April 1917, the nation was totally unprepared to fight a modern war in Europe. The U.S. Ordnance Dept. immediately sought to procure additional machine guns, primarily the U.S. Model 1915 Vickers, to augment the meager number of automatic arms in the government’s inventory. It took more than a year, however, to get the machine guns into any semblance of mass production. In the meantime, our troops in Europe were forced to use the Model 1914 Hotchkiss and other machine guns from the French until American-made machine guns could arrive on the scene.

In 1901, John Browning patented the design for a recoil-operated, belt-fed machine gun that was markedly different from his gas-operated Model 1895. There was little impetus at the time to spur development of a new machine gun, and Browning concentrated most of his efforts on designing guns for the more lucrative commercial market. As America’s entry into the war became increasingly likely, however, he began renewed development of his new machine gun design. In early May 1917, a prototype Browning water-cooled gun was ready to be tested alongside a number of other machine guns—of both foreign and domestic design—in trials held at Springfield Armory. The Browning’s initial test results showed a great deal of promise, and the inventor continued further refinement of the gun.

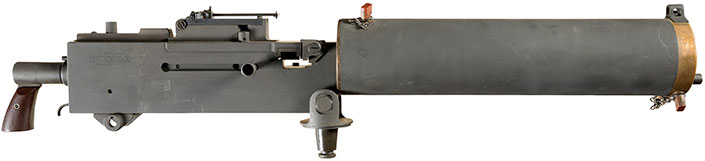

The Browning machine gun was kept under wraps until it was sufficiently developed to permit a demonstration to be held on Feb. 27, 1918, at Congress Heights, just outside of Washington, D.C. High-ranking U.S. Army officers, key Congressional leaders, some members of the press and other dignitaries were present. The assembled observers witnessed a demonstration of the remarkable firepower and reliability of the new Browning machine gun. The recoil-operated, belt-fed Browning weighed just over 34 lbs.—with a filled water jacket—in addition to the sturdy tripod which tipped the scales at 50 lbs. It fired at a rate of about 500 rounds per minute. Each loaded 250-round fabric belt weighed about 15 lbs., which brought the combined weight of a loaded gun mounted on the tripod to approximately 100 lbs. There was a “traverse and elevation” (T&E) mechanism mounted on the gun that permitted accurate adjustments for long-range and indirect fire. While the water-cooling system increased the weight, it gave the gun unparalleled firepower, as it could be operated for extended periods without the danger of extreme overheating. A condensing can was later added to channel the steam that formed in the water jacket through a hose and into the reservoir to be cooled. This helped prevent escaping plumes of steam from revealing the position of the gun crew.

Additional testing was conducted and continued to validate the gun’s impressive performance, and it was subsequently adopted as the “Machine Gun, Browning, .30 Caliber, Model of 1917.” Contracts were given to Colt, Remington and New England Westinghouse. While these firms were gearing up for mass production of the Model 1917 Browning, U.S. Army troops in France continued to use the French Model 1914 Hotchkiss machine guns. The first Model of 1917 machine guns were sent to France and demonstrated to American and Allied officers on June 29, 1918. Camps were established to instruct Ordnance Dept. personnel in maintaining and repairing the Brownings and to train troops in use of the gun.

Although 30,582 Model 1917 Browning machine guns were sent to France during the war, only 1,168 actually made it to the front lines to see combat service prior to the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918. The first recorded combat use occurred on Sept. 26, 1918, in the hands of Doughboys from the U.S. Army’s 78th Division. A report from the commanding officer of the division’s machine gun detachment to Gen. John J. Pershing stated: “During the five days that my four guns (M1917 Brownings) were in action, they fired approximately 13,000 rounds of ammunition. They had very rough handling due to the fact that the infantry made constant halts, causing the guns to be placed in the mud. The condition of the ground on these five days was very muddy, and considerable grit and other foreign material got into the working parts of the gun. The guns became rusty on the outside due to the rain and wet weather, but in every instance when the guns were called upon to fire, they fired perfectly. During all this time I had only one stoppage, and this was due to a broken extractor.”

The assistant secretary of war also relayed a report from another officer of the American Expeditionary Force regarding the superior performance of the Model 1917: “These guns went into the front line for the first time in the night of September 13. The sector was quiet and the guns were practically not used at all until the advance, starting September 26. In the action that followed the guns were used on several occasions for overhead fire, one company firing 10,000 rounds per gun into a wood in which there were enemy machine-gun nests, at a range of 2,000 meters. Although the conditions were extremely unfavorable for machine guns, the guns performed well. Machine-gun officers reported that during the engagement the guns came up to the fullest expectations and, even though covered with rust and using muddy ammunition, they functioned whenever called upon to do so.

“After the division had been relieved, 17 guns from one company were sent in for my inspection. One of these had been struck by shrapnel, which punctured the water jacket. All of the guns were completely coated with mud and rust on the outside, but the mechanism was fairly clean. Without touching them or cleaning them in any way, except to run a rod through the bore, a belt of 250 rounds was fired from each without a single stoppage of any kind.”

A senior American Army officer, Gen. Hunter Liggett, praised the Model 1917 Browning in his post-war memoirs, in which he opined: “The American Army used the Hotchkiss bought from the French, until our Brownings arrived. The Browning was the most dependable and foolproof of all—French, German or British … and the best machine gun that appeared in the war.”

Hand-drawn carts were developed to make transport of the heavy guns and ammunition easier. While no meaningful number of the machine gun were employed in the war, several cart variations remained in service up through World War II.

Even though the Browning machine gun only saw active combat during World War I for a few weeks, it was an impressive gun indeed. By the time of the Armistice, 41,804 Model 1917 Browning machine guns had been produced (counting the 30,582 that made it to France). Production continued for a short time after the war and, by the end of December 1918, a total of 56,608 guns had been manufactured. Had the war lasted into the spring of 1919 as projected, the Model 1917 Browning would have replaced the other machine guns in use by our Doughboys.

Given the Browning’s stellar performance in World War I, it remained the standard infantry machine gun in U.S. military service throughout the post-World War I period. In the late 1930s, a slightly modified variant, the Model 1917A1, was adopted. Most of the existing Model 1917s were updated to the M1917A1 configuration. These guns subsequently saw widespread use during World War II in all theaters. They proved their mettle on many battlefields, and were particularly effective against the Japanese massed infantry charges in the Pacific. The Model 1917A1 Browning machine gun remained in use during the Korean War. Once again, when called upon to do so, it proved to be extremely valuable against the hordes of advancing Chinese Communist troops. There were few infantry arms that could approach the level of sustained fire as the water-cooled Browning machine gun. The design was in service into the late 1950s when it was eventually superseded by other guns, including the M60 machine gun.

The .30-cal. water-cooled Browning was heavy and cumbersome, which made rapid movement problematic. When mounted on its sturdy tripod in a defensive position, though, it was a rock-solid arm with tremendous firepower and amazing reliability. It has been called the best machine gun of all time. That is obviously a highly subjective statement, but even if the Browning was not in a class by itself, like the old saying goes, “it doesn’t take long to call the roll.”