This article appeared originally in the March 1974 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the monthly magazine, visit NRA’s membership page.

Disclosure of details of the M1 carbine development came as a technical "last testament" from Edwin Pugsley, an all-time figure in firearms development. He died Nov. 19, 1975, at 90, after a long career with the Winchester Repeating Arms Co. At his retirement in 1950, he headed the research department of Olin Industries. Winchester at that time bought his personal arms collection, assembled during half a century, to round out the outstanding company collection begun in 1866 by Oliver F. Winchester.

By E. H. Harrison

It has taken more than 30 years for the complete story of the creation of the M1 carbine to come to light, but at last it has.

For the first time, a true account of the able firearms experts who carried out this successful development in haste under wartime pressure can be given.

The historical fact-finding resulted from publication of the article by Technical Editor M. D. Waite, "All The Way With The M1 Carbine," ( The American Rifleman, Sept.—Nov. 1974), giving the remarkable history of the development and huge production of the U.S. cal. .30 carbine.

That article merely mentioned (p. 42, Sept., 1974) the action of Winchester in developing the carbine which won an official competition and was then produced in vast quantities. The late Edwin Pugsley, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company vice president who submitted this design to the government, and David M. Williams, who invented the well-known gas tappet operating mechanism on the barrel, both were mentioned. Subsequently, The American Rifleman received a letter stating that another Winchester employee, of the same surname as the letter writer, "invented the carbine and should be credited with its design."

The American Rifleman thereupon contacted Edwin Pugsley, then retired, who supervised the M1 carbine program throughout. He stated as follows:

"The carbine was invented by no single man, but was a combination of parts of guns already produced by Winchester, and the work of several of our best mechanics of which Mr . . . . . 's father was one." He then recounted the carbine's history from the beginning, describing its inception and then detailing the work of those who took part by name and by the contribution of each.

The account contains allusions which he knew would be familiar to The American Rifleman staff to whom it was addressed. Where these may not be readily understandable to the reader, brief explanations are inserted in brackets.

Following is Pugsley's account in his own words, assembled from three letters in which he gave this history to The American Rifleman.

"I had charge of the Washington contacts for the Company prior to and during World War II, and began spending considerable time in Washington. Prior to World War II it was quite evident that war clouds were forming rapidly, and at a meeting of some of the Winchester executives with Mr. John Olin present, I told the group that I thought we should be actively working on a military rifle and not get caught without one as we had been in World War I. At that time we had two new model guns ready for production. One was a bolt-action sporting rifle easily converted to a military arm. It was in fact later brought out first as the M/54, and later refined into the M/70. Winchester had had no experience with heavy caliber bolt actions other than the .303 Enfield, as all of our guns were lever action—most of them unable to handle as heavy a round as the .30-'06 although we did furnish a few of our Model 95's for this caliber. The other choice was a new type of autoloading shotgun.

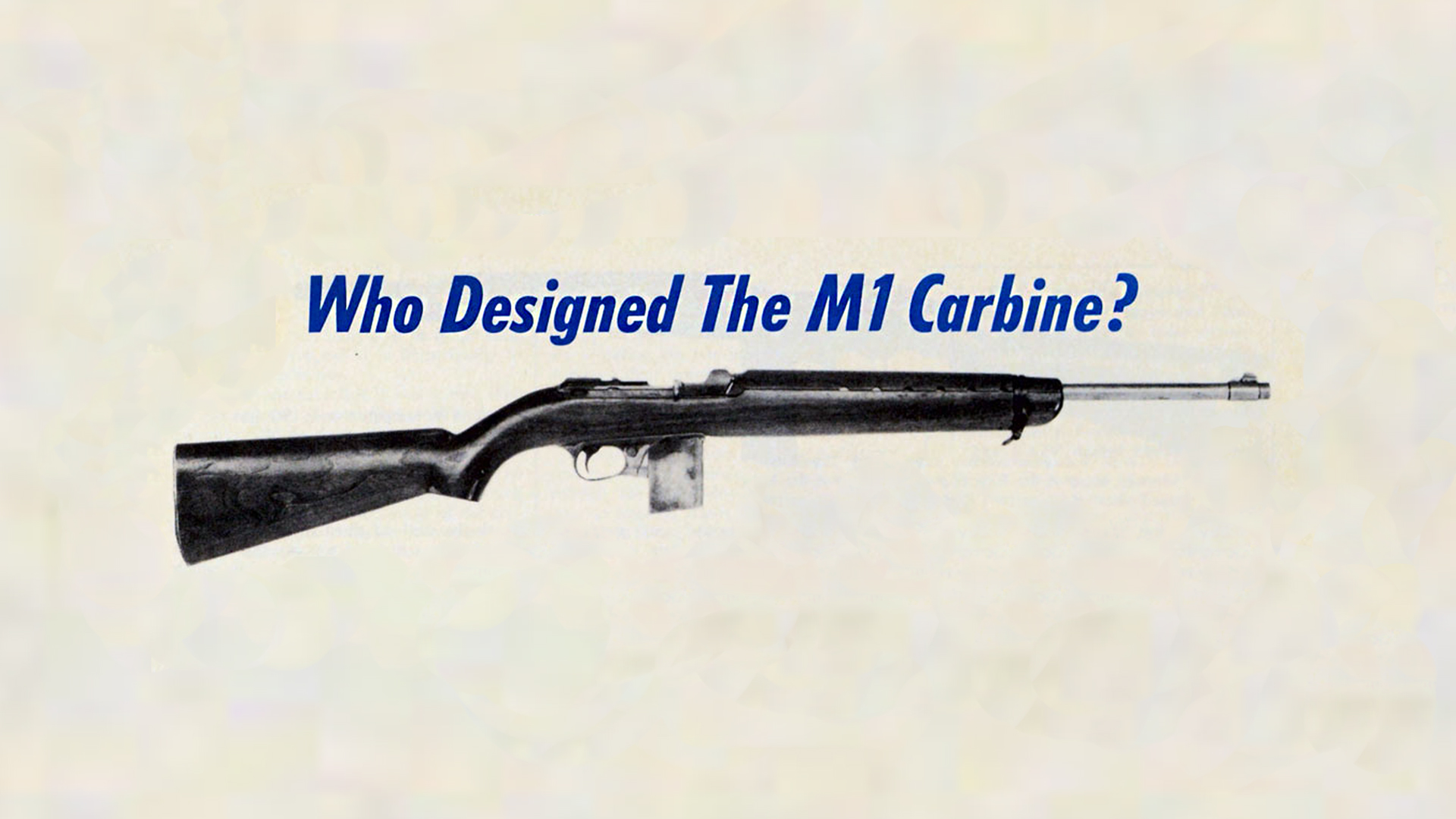

Final trial version of Winchester cal. .30 gas-operated rifle.

Final trial version of Winchester cal. .30 gas-operated rifle.

"The shotgun won out, and we were told to proceed with the development. However, due to my continued insistence on a military bolt action, Mr. Olin softened a bit and said, 'All right, go ahead, but don't spend any money.' I replied that this was like the old lady telling her daughter who wanted to go swimming that she could, but saying, 'Yes my darling daughter, leave your clothes on a hickory limb but don't go near the water.' However. T went ahead to see what we could do.

"Ed Browning [Jonathan Edmund Browning], half brother of John and Mat, had developed an autoloading military rifle and had submitted it to Washington. I went down to see it and to hear what results I could of the government's test. It was obvious that the gun was not right, but it had a few interesting features that I thought might be developed. I bought the model and hired Ed Browning to come to Winchester and continue working on it. [While engaged in this work Browning died following an appendectomy in New Haven on May 16, 1939, at age 80.]

"At about the same time I met Marshall Williams and after a long and arduous negotiation hired him too. When he came to New Haven, the first job I assigned to him was to see what could be done with the Browning Automatic [left unfinished by the death of Browning]. In a short time he brought me the revamped gun, cal. 30-'06. In the rearward travel of the bolt, it disappeared into the pistol grip, and the overall length of the rifle was shorter by the length of one .30-'06 round. Williams had incorporated his short-stroke piston in the new gun, which worked very well. Due to its shortness it was a nice gun to handle. I immediately got in touch with Col. Studler who came up from Washington the next morning, and we spent the morning shooting the new .30-'06 gun."

[Major (later Colonel) Rene R. Studler was Chairman of the Ordnance Subcommittee charged with providing for test of light rifles, the original name for the arm eventually adopted as the carbine. See the article "All The Way With The M1 Carbine" mentioned earlier.]

““Studler got me to one side and told me confidentially that none of the light rifles which had been submitted was satisfactory and that Winchester just had to put in a model for the next test. Due to our development work on the transformed Browning, and the work on the Garand, we had paid no attention to the government bid for a light rifle. At Studler's insistence I agreed that Winchester would have a gun in the next test as I saw from the work on the transformed Browning that we could get the weight down to the required 5 lbs., particularly using the small carbine cartridge. We had already developed the carbine cartridge and had received an order which we were currently making.

"As soon as Studler left, I called together the group I wanted to put on the new light rifle. In the group were Bill Roemer, my chief draftsman, Marsh Williams, Humiston, Clarkson, Warner, head of the Experimental Shop, etc. I showed them the .30- '06 gun on which we had been working, and, since we had used Williams' short-stroke piston, I put him in charge of the group. I told them that the sky was the limit as far as speed was concerned. No single man was responsible for the invention of the carbine, but basically it had several features of the .30-'06 Winchester gun produced by a group of our best mechanics.

"I had to go to Washington and was gone three days, expecting to find a lot of work done on my return. I was disgusted to find that due to Williams being unable to pull the design out of his head fast enough to keep the mechanics busy, nothing had been accomplished. I replaced Williams with Roemer, putting him in charge of the group. That group, as you know, tore the cover off the ball and in five days we had a sample of the new small rifle destined to become the .30 Cal. Carbine.

"I called Studler up from Washington, and he came the next morning. We shot the gun all the morning, and Studler said he would take it back to Washington with him, but I refused to let him have it because of the fact that some of the parts had been soldered and some were not properly hardened due to the rush in which the sample gun had been made. However, I told him that I would bring the gun down to Washington for a demonstration whenever he wanted it.

"He called me that evening and wanted me in Washington the next morning by 10 o'clock. I went before a group consisting of some 20-30 high level brass and demonstrated the gun. Gen. Courtney Hodges [the Chief of Infantry] was chairman of the meeting and, while I had never met him before, I knew him by reputation as an excellent shot and a member of the International Rifle Team. When he hefted the rifle his remark was, 'This feels like a rifle.' Someone remarked that the gun still belonged to Winchester and maybe it wouldn't work. Gen. Hodges quietly replied that if Winchester had sent it down it probably would work—one of the finest compliments I ever heard.

"Immediately after the meeting I assembled the men whom I wanted to put on the job, which included Bill Roemer, Fred Humiston, Cliff Warner, head of the Experimental Shop, and one or two others among our most expert and fastest mechanics. These men were supposed to make a second model to be submitted to the government test. They were to follow the design of the forerunner. Bill Roemer immediately started making sketches of the parts. However, a few of the simpler parts were made without sketches by men like Humiston who were able to visualize the part needed.

"When we made the second model we drilled a very small gas port, as I remember .080", and the gun would not go through a magazine-full without a failure. We had worked all the previous night, and the last train for Aberdeen left at midnight Sunday. Studler called up from Washington to ask how the gun was going, and I told him I didn't know. He wanted to be sure that we were going to have a gun in the test, and I said that we would not unless it worked better than it was working at the moment.

"Three of us went out to a diner for a sandwich on Saturday noon, and we were a pretty discouraged bunch. I finally decided that the gun was not getting gas enough, and discussed it with the other two. I then decided that we would take a chance and enlarge the port. I knew that if I had guessed wrong the gun would be out of the test, but it was not fit to go in as it was. We all agreed that it was a reasonable chance, and we retired to the big Machine Shop on the first floor. The Experimental Shop with a sensitive drill press was on the fifth floor, and there were no elevators running. Williams thought he could hold the barrel in his hands under the big drill press and tried it, only to break the drill off short in the hole. Consternation set in but I was not too worried as I was sure we could shoot it out, which we did. With the larger gas port the gun ran 300 rounds without a stutter, and I told the crew that we would catch the midnight for Aberdeen.

"The next question was who should take it down. There were several possibilities. Normally I would have sent it down with Williams because of his greater experience in government testing. However, by this time he had lost interest in the gun and was busy making a new model. I finally chose Humiston because of his familiarity with the gun and his outstanding capabilities as a mechanic. It was his first assignment of this type.

"He took the gun to the test, and it performed so much better than any of its competitors that it got well ahead of the field. Then one evening about five o'clock he called me at my shore house saying they had broken the operating lug off the bolt. I told him to come back to New Haven that night and be in the factory as early as possible the next morning. I knew that we had two or three days' lead over the field, and there was a possibility that we could get a bolt back into the gun before it would be called on to be tested again. The government refused to let us take either the gun or the broken bolt.

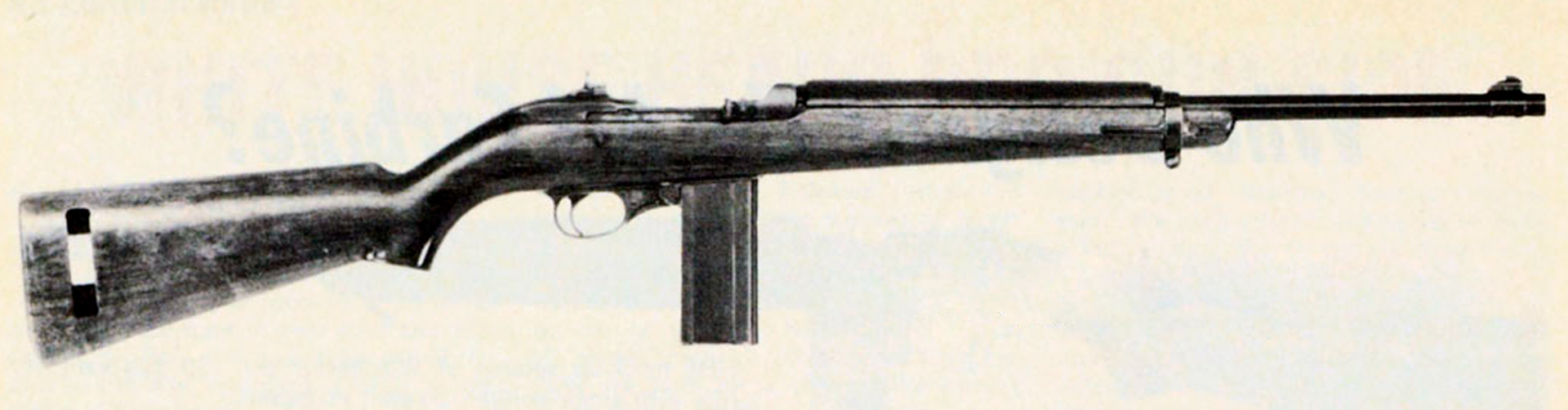

Cal. .30 M1 carbine of early manufacture had a 15-round detachable box magazine and L-type rear sight, but lacked bayonet attachment.

Cal. .30 M1 carbine of early manufacture had a 15-round detachable box magazine and L-type rear sight, but lacked bayonet attachment.

"Immediately after Humiston's call I got in touch with Bill Roemer and Cliff Warner and told Warner to bring into the factory immediately any help that he needed to rough out a new bolt. We all met at the Experimental Shop at about six that night and started roughing out the new bolt. Roemer had a few sketches but not a complete drawing; however, we rough-turned the outside, drilled the firing pin hole and did whatever rough operation we could, leaving the plant well after midnight. The next morning Fred Humiston came back from the test [at Aberdeen Proving Ground] and finished the semi-machined bolt by that night, relying on memory wherever details were missing. He took the bolt back to the test, and miraculously it fitted and finished the test. The gun was the unanimous choice of the entire Committee without a single dissenting vote. Contractors were called in immediately to get it into production.

"Due to the fact that it was a new type of gun, many of our former Winchester patents could be reissued, which was done, and several men took out patents on various parts, myself among them. The .30-'06 revised Browning model, which might be called the grand-uncle of the carbine, is still in the company museum.

"The adoption of the different mechanisms comprising the carbine, whether covered by said patents or patent applications, or mechanisms generally known to the trade, was determined in conference by the team under my supervision. As examples, I might mention using the guard and its components complete from the old Winchester M/1905 including the interrupted trigger, the housing of the return spring copied directly from the Bang gun, the short-stroke piston then belonging to Williams but later acquired by Winchester, the take-down device taken directly from one of my double-barreled percussion shotguns, and the cutting away of both sides of the receiver wall from the Garand, thereby greatly simplifying the ejection.

Trigger Guard Findings

"It was very important that Bill Roemer found that the Winchester Model 1905 trigger guard complete with interrupted trigger mechanism could be fitted with very little alteration to the carbine. This saved making a special trigger guard and inventing a new interrupted trigger device. The interrupted trigger was necessary to get only one shot each time you pulled the trigger. Without it you could not release your finger on the trigger quick enough to prevent a small burst of two or three shots. The Model 1905 mechanism was all completely tested out and had been on the market for some time. This saved us at least a week in producing the first carbine in something like five days.

"It is interesting to note that in the production of the carbine fewer changes were made from the original Winchester design than in any other military rifle we produced. Changes in the Garand were continually being made during its production, but this was not the case with the carbine."

This story in detail of Winchester's acceptance of the carbine challenge and development of the successful carbine in the Winchester plant, fills out M. D. Waite's "All The Way With The M1 Carbine" (The American Rifleman, Sept.-Nov., 1974), giving the history of the whole carbine competition and the successful carbine's large-scale production and use. It is interesting to see how closely these histories fit together.

Pugsley's account is fascinating in itself. made as it is from the standpoint of the Winchester engineers and mechanics who carried out the development, and recounted by the company officer who directed their work and was one of them.