When on the staff of this magazine many years ago, I was invited to Springfield, Mass., for the unveiling of the world’s most powerful handgun—the vaunted Smith & Wesson Model 500 chambered in the then-new .500 S&W Mag. cartridge. It was monstrous and beautiful at the same time. What impressed me most, though—once you got past the power and novelty of the piece—was the fact that it was just a darned fine gun; well designed, finely crafted and highly accurate. Moreover, it was conceptually interesting. Having learned from the success of the wildly popular Model 29 that Clint Eastwood carried in the “Dirty Harry” movies, the company was eager to win back and forever retain the title of “world’s most powerful handgun.” To that end, Smith & Wesson went to ATF and found out the maximum ballistic specs the law would permit, allowing it to make a handgun whose power could not be excelled.

It was a masterpiece of planning, permanently establishing the company at that end of the firearm spectrum. More recently, I was invited to attend the release of the pistol that may permanently stake out territory at the other end of the spectrum—the .22 Long Rifle SW22 Victory.

Small Caliber, Big Importance

That the Massachusetts gunmaker should focus its attention and resources on the diminutive rimfire underscores the importance of the chambering. If you think about it, the .22 Long Rifle has more utility than any other cartridge. From plinking to formal target shooting, from pest control to small-game subsistence hunting, and from inclusion in every field kit to introducing youngsters and newbies to shooting, the .22 Long Rifle is usually the first choice and is, therefore, ubiquitous. That versatility makes the .22 Long Rifle pistol market pretty lucrative. Moreover, that last duty—introducing young people and new shooters to firearms—can have the tremendously important effect of establishing brand loyalty. Virtually all of us can recall the make and model of our very first firearm, and affection almost always accompanies that recollection.

The Target

While it’s difficult to associate the .22 Long Rifle with might, Ruger’s Mark series has long been the rimfire equivalent of the Death Star—imposing, all-powerful and seemingly without vulnerability. Smith & Wesson’s chief domestic rival most recently was the Mark III. The groundbreaking, market-altering Mark I evolved, in the course of nearly seven decades, into the Mark III, a pistol so good and so versatile that its domination long went unquestioned. It could be configured for anything a rimfire was suited for, was affordable, simple to operate and reliable.

However, like the Death Star, it had a single vulnerability that Smith & Wesson recognized and sought to exploit. OK, we all saw it; S&W just decided to do something about it. The fact is, the Ruger pistol has always been very difficult, if not impossible, for the average consumer to reassemble. You either learned the trick through seemingly endless trial and error or, more typically, had a gunsmith reassemble it for you and never took it apart again.

Smith & Wesson’s SW22 Victory is the shot down the vent of Ruger’s Mark III.

The charge that the Victory delivers is modularity—the pistol takes down with a single Allen-head cap screw. The receiver eases off the grip frame and the bolt slides out. Thus, access is afforded to the internals as well as allowing the chamber and bore to be cleaned from the breech. Granted, the creation of the BoreSnake and now the Ripcord makes this less of an issue, but still … . Besides, it gets even better. Turn another screw and, yep, you can remove the barrel. This is huge. Why? Because it means the Victory’s modularity doesn’t just target the difficulty in taking down the Mark III; it also targets the Ruger’s inability to be easily reconfigured. The Ruger Mark III can be purchased or subsequently set-up for any rimfire task, but because the Ruger’s barrel is permanently affixed to its receiver, reconfiguring it for another purpose is all but impossible without the purchase of another barreled receiver, the latter of which, of course, requires an FFL transfer. The modularity of the S&W Victory allows the owner to easily mix and match components, including barrels. What other components, you ask? Oh, we’ll get to that.

Time And Space

The last challenge that Smith & Wesson faced when taking on the Mark III was its long-established presence in the market and the consequent existence of a big aftermarket. Check Brownells or Volquartsen Custom. A whole cottage industry exists for the Mark III. You can have it tricked out in every way possible for any task that’s practical. How do you confront the existence of a long-established aftermarket? Well, if you’re Smith & Wesson, you do it head-on.

Like the Millennium Falcon jumping to hyperspace, Smith & Wesson seemingly challenged the laws of time and space by creating an aftermarket before the fact. It went directly to Volquartsen (volquartsen.com), explained what the company was up to and had Volquartsen create two premium barrels that would be ready and waiting when the Victory hit the market. Both rubber and laminated aftermarket target stocks were soon to follow.

The Volquartsen barrels are things of beauty. One is a long, bullseye-type with a threaded muzzle fitted with a compensator that is so perfectly machined that you cannot see the seam where it meets the barrel. The other is a shorter, carbon-fiber-shrouded unit that is lightweight, yet stiff, and has a thread protector over its threaded muzzle. It just begs for a suppressor.

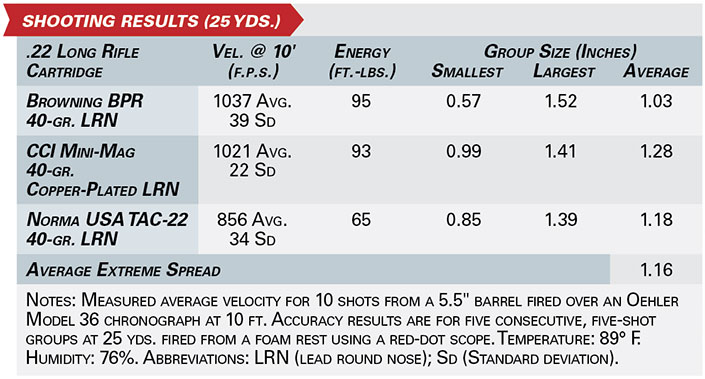

Shots Away!

In both concept and execution, the Victory is every bit as brilliant as the Model 500, and maybe more so. The pistol, which is available in both satin stainless steel and camouflage, is sleek and handsome. There is no readily apparent visual evidence of its modularity, no aesthetic price paid for its hidden abilities. Moreover, the Victory feels solid. There’s no looseness or slop; nothing to indicate that the alignment of the components is anything other than permanent.

The black plastic stocks are not great but rather “universally satisfactory.” The Victory will be handled by shooters of every size, shape and skill level for every task imaginable, so fitting as many people as possible is important. Besides, aftermarket units are easy to install and are already available from both Volquartsen Custom and Altamont.

The cocking ridges on the rear of the bolt flare slightly, making the bolt easy to grasp and rack. The steel-reinforced thumb safety has a polymer surface for comfort and good purchase. The trigger has an adjustable stop, allowing you to fine tune it to your preference. The two included magazines are excellent—rigid and smooth. Scallop cuts in the stock panels make them easy to extract.

The sights, too, are outstanding. The adjustable rear unit has a green, semi-circular fiber-optic pipe, the ends of which form two dots bracketing the square notch on the face of the sight. The front blade incorporates a single straight pipe, giving you a bright, three-dot sight picture. However, yet again with a single screw, the rear sights can be removed and replaced with a lightweight Picatinny rail, allowing for optical sights. The rail even has a fixed rear sight on it that works with the front blade, should your optic fail or you just decide to switch to irons in the field.

The stock barrel may be the star of the show. By general acclaim, a 5.5" bull barrel is about the best all-around unit you can put on a .22 pistol, and that’s what this is. It is available from S&W with a target crown or threaded and capped. It makes the gun handy, is quite steady, and provides decent sight radius and good velocity. Need a lighter platform? Order the carbon-fiber model from Volquartsen. Need additional velocity and recoil attenuation? Yep, Volquartsen again.

Honestly, the stock barrel does everything well. I don’t mean just OK, either. It is remarkably accurate. The Victory was created with an eye toward Smith & Wesson’s legendary Model 41 accuracy standard and design attributes of the company’s discontinued Model 22A. That said, it’s also nice to explore different components just because, well, you can. With only a screwdriver you can create a task-specific configuration—then change it back or create a new one with equal ease.

Stay Tuned

The thing is, the Victory’s modularity, incredibly welcome as it is, could easily have been a mere stunt. Being able to take apart and reassemble a bad gun is a very dubious thrill. And who cares about reconfiguring a gun that performs poorly at everything? The Victory evinces excellence at all things rimfire. It compares more than favorably to any moderately priced, general-purpose rimfire pistol out there before you factor in the modularity. It’s that good.

But is “that good” good enough to supplant the Ruger? Was Smith & Wesson’s aim true? Will the Death Star be destroyed? It sure looks like it—but wait. At this writing, Ruger has just introduced the Mark IV, the successor to the Mark III, and this time it quickly takes down and easily reassembles. We’ll have to keep following the story and see what happens.

You know, sometimes the empire strikes back.