This Veterans Day, Nov. 11, 2020, marks not only the 66th anniversary of the holiday, but the 102nd anniversary of Armistice Day as well. Every Nov. 11, we remember those men and women who have served our nation in the United States Military. While the official holiday held every year is meant to honor those who have served and survived, it had a different intention at first, directly connected to the end of hostilities in World War I.

While World War I came to an official close on June 28, 1919, with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the fighting had ended months earlier with an armistice that began on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918. In November 1919, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed Nov. 11 as Armistice Day in remembrance of those American servicemen who had given their lives during World War I, observed with parades and a cessation of business starting at 11:00 a.m.

Through an act of Congress passed in May 1938, Armistice Day was approved as an official legal holiday to be held every Nov. 11, but changed to honor the surviving veterans of World War I instead of the fallen. It was changed again in June 1954, under pressure from veteran service organizations after World War II and the Korean War, to Veterans Day as a commemoration to the American veterans of all wars. Thus, not only does every Nov. 11 holiday commemorate those who served, but it also marks the anniversary of the armistice that ended the fighting of World War I.

That day was especially memorable for two U.S. Army veterans of the Western Front, as the 11 a.m. cease-fire saved them both from near certain death. Max B. McKee, a former captain of Company D, 340th Infantry Regiment, 85th Infantry Division, received a letter from a former subordinate, Harry A. McCullough, in September 1970 that brought his shared memories of that day back to mind. Both men were on the front lines between Verdun and Metz, France, on Nov. 11, 1918, poised for an assault against German lines scheduled for that morning.

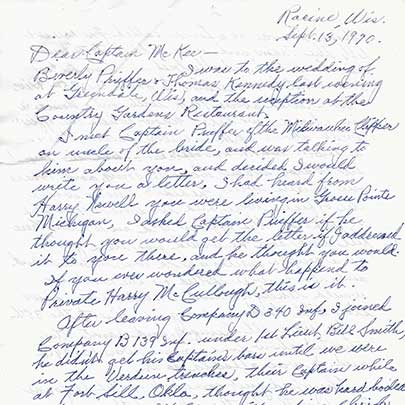

McCullough was at a wedding on Sept. 12, 1970, when he met the uncle of the bride who was the captain of a Great Lakes passenger ship, the SS Milwaukee Clipper. During a discussion with the captain, McCullough learned that the ship was owned by a man named Max McKee. It was the same name as one of McCullough’s former officers during World War I, before he changed units.

McCullough's Letter and Experience

McCullough then found out that the owner was in fact the same man who was his captain when he was assigned to Company D of the 340th Infantry Regiment in France. After finding this out, McCullough decided to write a letter to his former captain to catch up, share memories of the last days of the war and life after. In the letter, former Pvt. McCullough recounted how he was transferred from Company D of the 340th Infantry Regiment to Company B of the 139th Infantry Regiment, 35th Infantry Division in early Nov. 1918.

The 139th Infantry Regiment had just come off the line from the Argonne Forest the previous month, where Company B had lost more than half of its men in the fighting there. Pvt. McCullough’s new unit was ordered to the front to join the rest of the 35th Infantry Division in the trenches near Verdun, France. The men got off the train near the French town of Fleury, and were ordered to leave their rations of hard tack and bully beef in two piles before marching to the front.

The men began their march to the front with only their non-commissioned officers in charge, with no idea where their officers where. As they passed another town, the men of Company B were stopped by an officer who warned them not to proceed to the trenches until dark, as their presence on the road ahead would attract German artillery. When night came, they finally moved out for the trenches at the front lines, led by a guide.

Once Company B made it into the trenches after dark, the men were starving as Pvt. McCullough recounted. They hadn't been issued new rations after leaving their old ones when they unloaded from the train in Fleury. A rations cart was wheeled to them full of bread, only for rats to ruin most of the load before it could be handed out to the men. Pvt. McCullough was helping unload what little was left of the bread rations from the cart when he stepped on something round in the mud. It turned out to be a loaf of French bread.

Pvt. McCullough hid and later washed off the loaf, dividing it up with three of his buddies in the trench. He kept a piece of his share in his pocket to eat in the morning. When he later woke up in the dugout the following morning, Pvt. McCullough found that a rat had eaten through his pocket as he slept and had taken the bread, leaving him hungry and unhappy. McCullough noted that “it was alive with rats up there.”

The following day, the company was ordered by their commander, Maj. McDonald, to wait by a crossroad for marching orders. This was close to the front and within sight of the Germans. When a German creeping artillery barrage began to rain in onto their position, the lieutenant left in charge ordered the company to move out of range of the barrage. When Maj. McDonald finally caught up with the group, he at first scolded the lieutenant for moving the unit without orders; he then slapped the lieutenant on the back and said, “You used your head. If you had stayed where I told you, you would have all been blown up.”

Company B and the rest of the 139th Infantry Regiment were in an old French encampment within a small forest on the morning of Nov. 11, 1918, geared up and poised to attack German lines near Metz. From 8 a.m. to 11 a.m., they waited for word to move out and begin their assault. Before the word to move out came, Maj. McDonald broke the news to the unit that the war was over.

McKee's Recollection of The Armistice

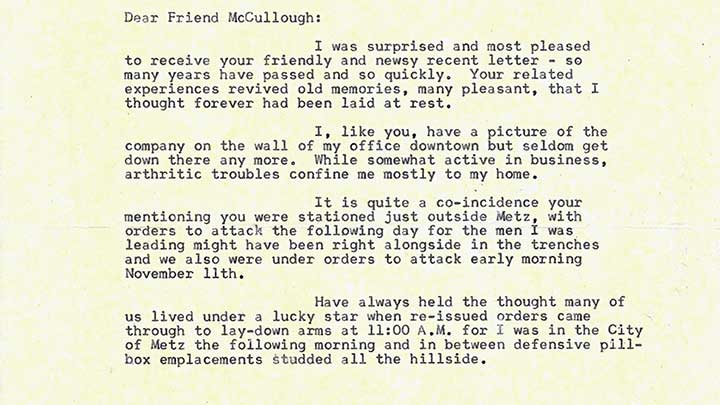

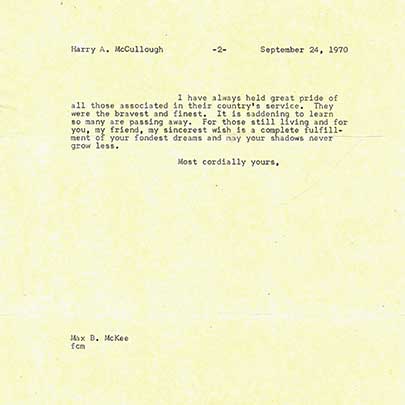

In response to McCullough’s letter, McKee sent his own in return to thank his former associate for reaching out to him and reminding him of those last days of the war. In his responding letter, former Capt. McKee mentioned the coincidence that B Company of the 139th Infantry Regiment was poised to attack the German lines near Metz. His own D Company of the 340th Infantry Regiment was also assigned to attack the same lines on the morning of Nov. 11, 1918, before the armistice was announced.

Capt. McKee recalled that his unit moved into the city of Metz the following day after the end of hostilities, and got an up-close look at the German positions they would have faced. There were pillboxes and machine gun emplacements all across the landscape that they would have advanced across. Capt. McKee stated that he “always held the thought many of us lived under a lucky star,” when he saw the reinforced German defenses. There was no doubt in his mind that the 11:00 a.m. cease-fire saved his life and the lives of his men.

McKee's M1911

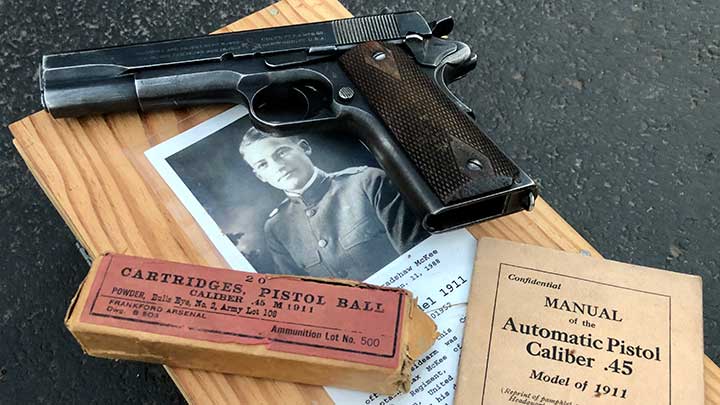

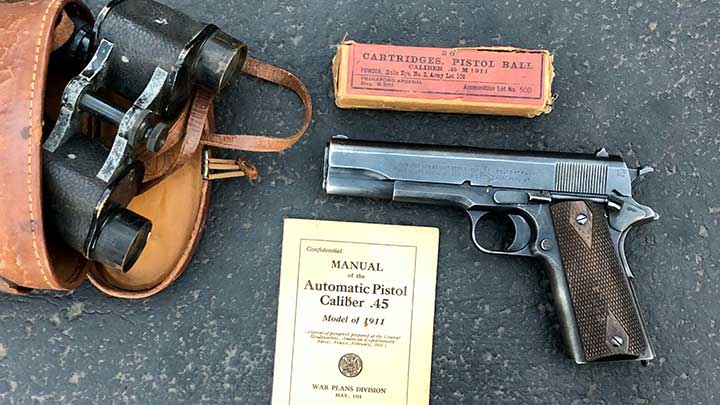

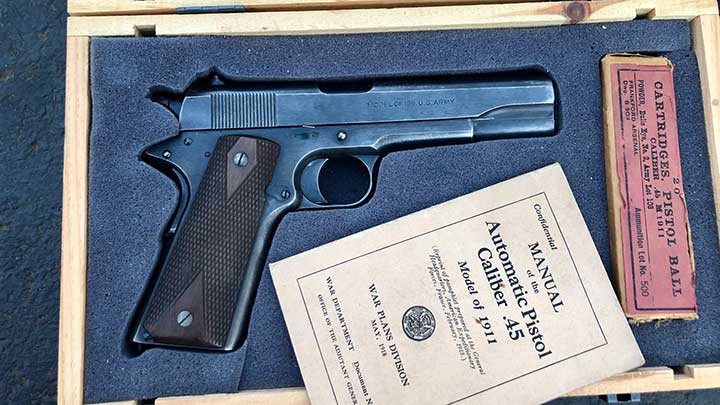

As an officer, Capt. Max B. McKee was issued a Colt produced semi-automatic Model of 1911 U.S. Army service pistol chambered in .45 ACP as his primary weapon during the war. Unlike other infantrymen and some non-commissioned officers, higher ranking officers like Capt. McKee were only issued sidearms instead of a rifle at that time. It is noteworthy that he was issued a M1911, in that there was a shortage of them throughout the war.

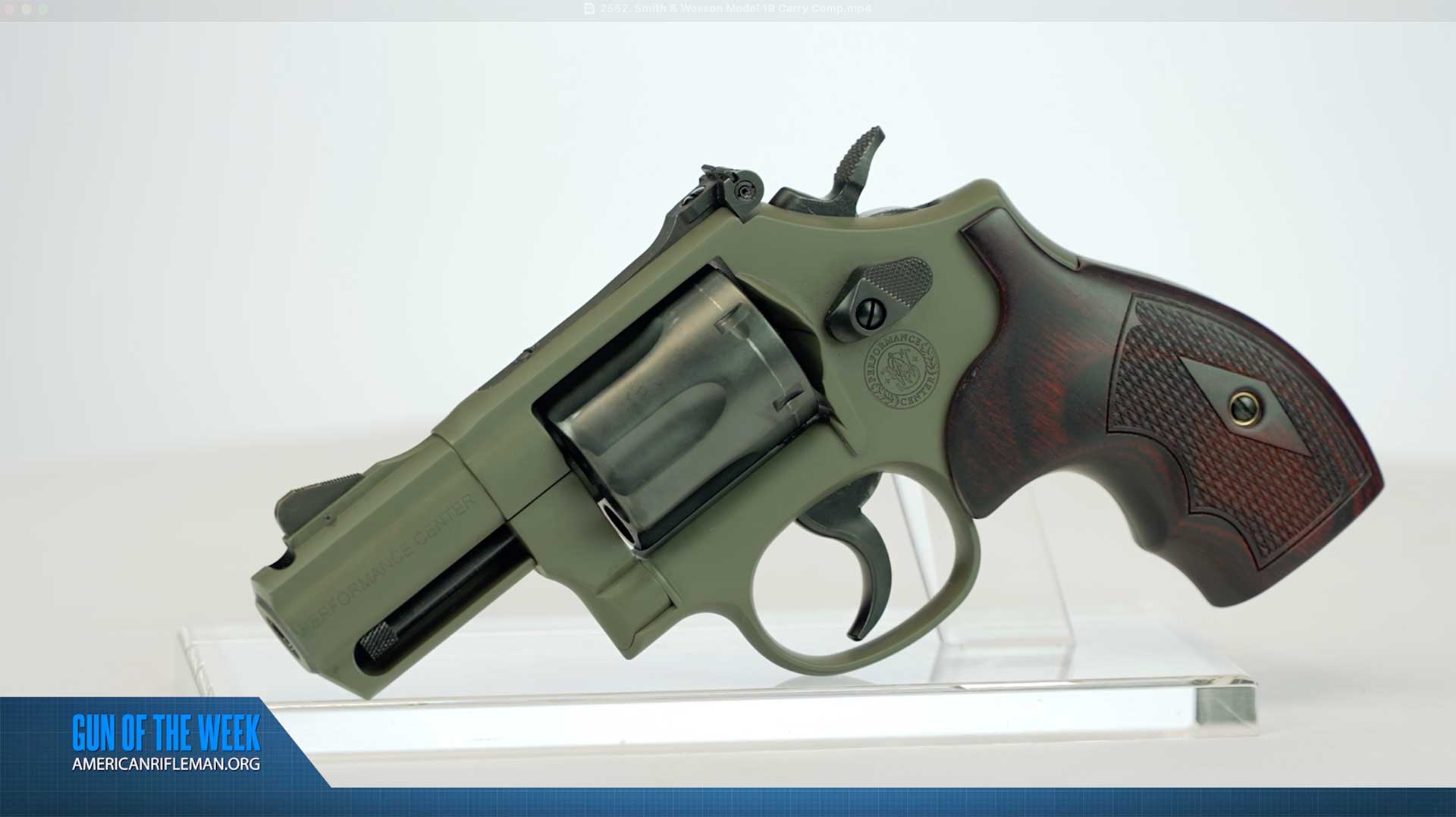

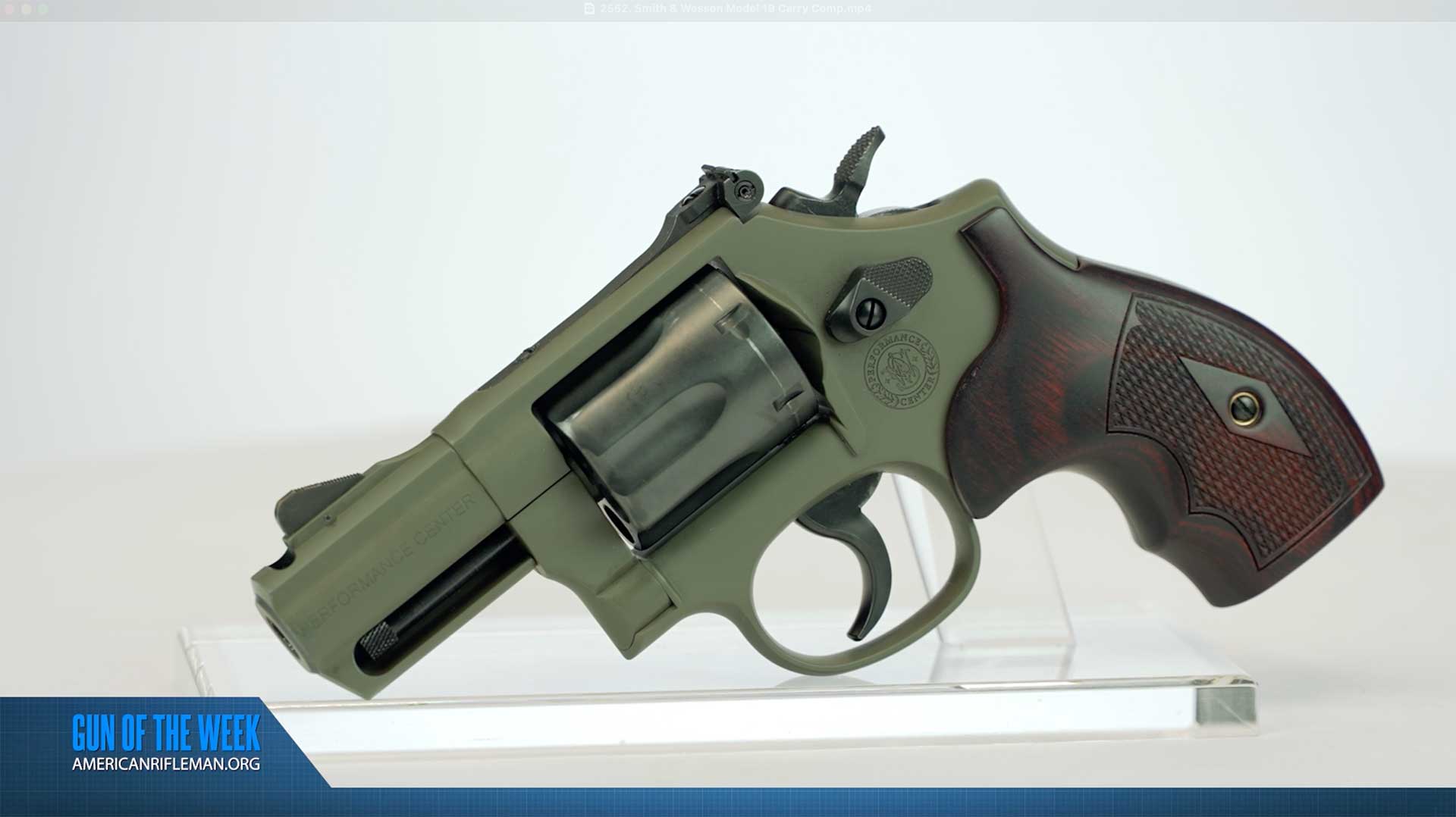

Production of M1911 service pistols at Colt and Springfield Armory fell way behind the demands and needs of the rapidly growing American Expeditionary Force in 1917. The lack of adequate numbers of M1911s to arm soldiers and officers resulted in the Ordnance Department turning its attention to other existing handgun designs to fill the gap. Much like how the lack of adequate numbers of M1903 rifles resulted in the adoption of the M1917 Enfield rifle, the lack of M1911s resulted in the adoption of Colt and Smith & Wesson M1917 revolvers.

Capt. McKee's M1911 was manufactured by Colt sometime earlier in 1918 and shipped sometime after May of that year. It's hard to determine when exactly his M1911 was shipped out, as the last shipment of consecutive serial numbers from Colt was sent out on May 5, 1918, a batch predating his specific pistol’s serial number. After this date, Colt’s records for military issue M1911s only included the number of pistols and a rough serial number range of the shipment’s contents, as it was simply trying to send them out as fast as possible. This makes it harder to determine the specific serial numbers included in the shipments.

Capt. McKee later privately purchased his M1911 service pistol, which some officers were allowed to do at the time if they could afford it. His M1911 is privately owned today and still in good condition 102 years later. All the roll marks are clearly visible and the original walnut stocks are in very good shape, given their age. The original blued finish is also in decent shape, with minor wear marks along the edges of the frame along with more noticeable wear at the front of the slide and frame from holster use. The worn finish on the front strap is from where Capt. McKee's fingers once held it.

Life After the War

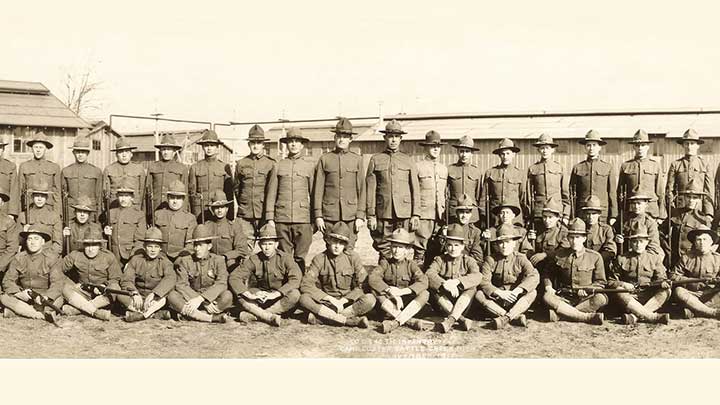

Max B. McKee returned to Michigan after the war, where he later became a successful entrepreneur and the president of the Sand Products Corporation in Detroit. He founded several other businesses including a Great Lake cruise company, Wisconsin & Michigan Steamship Company, which operated the SS Milwaukee Clipper along with other ships. In his office, he had a framed picture of D Company, 340th Infantry Division hanging on the wall to remember the men who served under him and their time in the war.

In his reply letter to McCullough, McKee wrote “I have always held great pride of all those associated in their country’s service. They were the bravest and finest.” This Veterans Day, we remember not only the service men and woman who have served throughout America’s history, but the doughboys like Capt. Max B. McKee and Pvt. Harry A. McCullough who served in the American Expeditionary Force during World War I. The sacrifice and bravery of those men, and men like them, is what ultimately lead to the creation of this holiday, celebrated on the same day as the armistice that saved their lives in 1918.