Triplett & Scott Arms produced a quite-unusual Civil War-era breechloader that was fitted with such an awkwardly placed magazine that most who looked at the gun decided it must have been added as a postscript. But a second addition to their guns was the opposite of awkward, an extractor device that, at the time, was pure genius.

At first look, the Triplett & Scott carbine was like many other carbines of the era, with a blued, five-groove, rifled barrel and basic iron sights. But on closer inspection, the Triplett & Scott carbine was quite unusual when compared with other Civil War-era firearms. Take the Maynard Carbine or Merrill Carbine for instance; both were single-shot firearms. The Triplett & Scott was more advanced as a repeating rifle because it held seven shots in the magazine. It was fabricated in such a way that the entire barrel was attached to the stock by way of a revolving hinge.

To operate the firearm, one would place the hammer on half cock, and depress the button for the catch on the rear of the receiver. With this done, the shooter could rotate the forward half of the receiver-clockwise. With this complete, an automatic ejector would extract the spent cartridge case from the receiver. Rotating the forward half even further would open a spring-loaded door that covered the magazine tube, thus allowing a cartridge to be inserted into the firing chamber. Now, rotating the action counter-clockwise locked the action. With this done, cocking the hammer back made the gun ready to fire. This does seem like the long way around, but with instruction, one could become rather efficient in operating the gun.

The Triplett & Scott tubular magazine was designed to sit within the buttstock. But there were problems with this setup. First of all, the magazine could not be detached; this meant one would have to reload the magazine one cartridge at a time. And barring the magazine loading problem, it also weakened the buttstock. The magazine was mounted in such a way that the wrist of the stock was virtually taken up by the magazine. This could cause the stock to break with just a little strain.

Where other rifles used paper cartridges, the Triplett & Scott carbine was manufactured to allow the hammer to strike a firing pin. This meant that the design employed metallic rimfire cartridges, making the firearm just one of a select few that used these type of cartridges at the time. The Triplett & Scott fired the .56-50 Spencer rimfire cartridge initially developed for the Spencer carbine. This cartridge was created by the U.S. Ordnance Department in an effort to systematize the rimfire metallic cartridge that was used in several patent carbines in military service, and the round was later used on the Western frontier through the late 1800s.

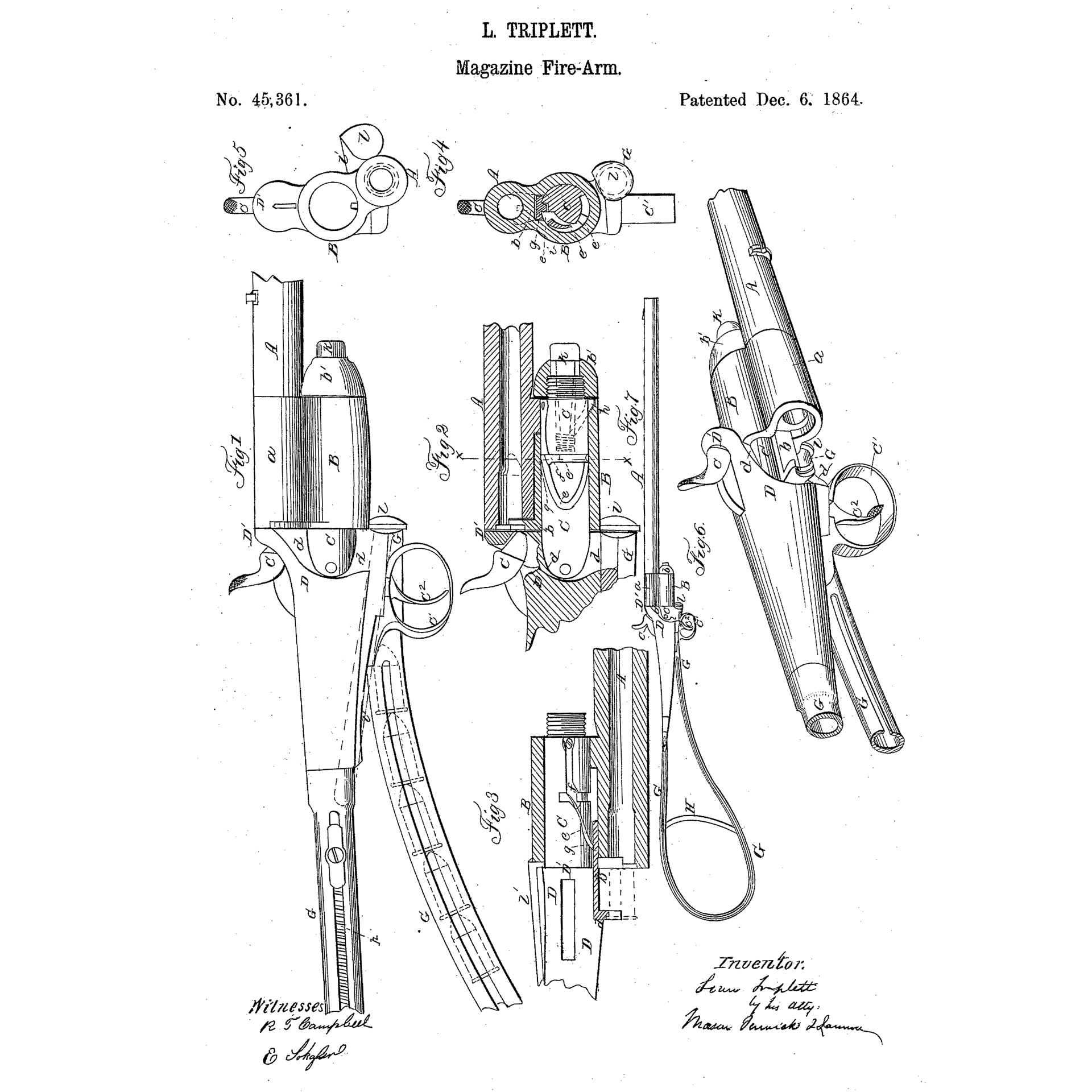

The story behind the Triplett & Scott firearms, both carbines and rifles, is rather unusual. The design presented to the U.S. Patent Office was submitted by Louis Triplett of Adair County, Ky. Triplett was granted a patent for a “magazine rifle” on Dec. 6, 1864, number 45,361. This was the only patent issued to Triplett, but peculiarly, this patent did not address the extractor and breech but surprisingly covered only the magazine. Possibly, the extractor never received a patent or perhaps a patent was issued in another person’s name. J. Richard Salzer’s article, "The Triplett & Scott Carbine," sheds some light on this quandary. Patent No. 37025 was issued earlier, on Nov. 25, 1862, to J. W. Armstrong and John Taylor. This patent claimed an extraction-and-breech principle, almost one and the same to the Triplett & Scott firearm. This leaves one to believe that either there was group effort between both gunmakers or possibly an infringement took place.

In delving into Triplett’s background, there is no sign that he had any fabricating or inventing skills. Somehow, Triplett made the acquaintance of William T. Scott who witnessed Triplett’s patent for an “improvement in magazine of self-loading arms.” This patent was then consigned to Charles Parker. Parkers’ Snow & Co. made Triplett & Scott repeaters, according to Triplett’s patent parameters for the government trials held in November 1864. The trials were not successful, as guns jammed when sand got into the action. Due to this, the repeaters remained unsold.

But it appears Scott possessed some political influence, as Kentucky’s Governor Bramlette directed Kentucky’s state adjutant general to commission W. T. Scott to produce 5,000 .56-50 Spencer-chambered longarms to be distributed to the Kentucky State Home Guard. The delivery of these firearms to the guard was important, as they were to protect Gen. William Sherman’s supply lines that trailed through Kentucky to Nashville, Tenn. This was not an idle peril, as these supply lines were facing attacks from rebel supporters and partisans.

At a loss as where to find firearms, as the usual arms manufacturers were not able to fill the order, Scott turned to the Meriden Manufacturing Company of Meriden, Conn. to produce Louis Triplett’s design. Wasting little time, on Jan. 2, 1865, he contracted for 5,000 .56-50 Spencer-chambered long guns with Meriden Manufacturing to make 3,000 of the rifles at $30 each, and 2,000 carbines at $22 each, equaling a total of $146,000. Each is marked with serial numbers and “TRIPLETT & SCOTT PATENT DEC. 6, 1864” on the breech tangs. The receivers are marked “KENTUCKY” on one side, and “MERIDEN MANUFG CO. MERIDEN, CONN.” on the other side.

The Meriden Manufacturing Company was formed by the aforementioned Parkers, Charles and Edmund, and William and George Miller. The order for the Triplett & Scott rifles and carbines was completed and delivered on the May 1, 1865, just under a month after the war ended, leaving firearms too late to be used during the American Civil War. With this, the majority of the arms remained with the state of Kentucky until 1870. Pursuant to the Indemnification Act of 1861, the Commonwealth of Kentucky applied to the federal government for reimbursement of the monies the state paid for the Triplett & Scott firearms.

Once the funds were returned to Kentucky coffers, the guns were sent to the federal arsenal located in New York. The $146,000 refunded to Kentucky was put to good use in helping to build the state capital building. Contained within this cache of arms sent to New York was 1,900 22” carbines and 2,810 30” rifles, all in new condition. Also included were 50 rifles “cleaned & repaired.” To complete this cache were 93 carbines and 133 rifles graded as “unserviceable.” In total, these numbers equal 4,986 long arms out of the original 5,000.

It wasn’t until three decades later that the New York Arsenal was able to sell 4,705 Triplett & Scott firearms to Kirkland Brothers. This transaction was completed in three installments at fire-sale prices; 2,349 were sold at $0.25 each, 545 at $0.10 each, and 1,811 at $0.20 each. Marcellus Hartley of Schuyler, Hartley & Graham fame bought 72 of the guns between $0.21 and $0.30 each. As for the remaining 209 Triplett & Scott guns that were stored at the New York arsenal, information on their fate has been lost to time, and the same is true of the 14 guns that never left Kentucky. Nothing more was heard of the arms until a number were sold in Bannerman’s catalog for $15 each.

Triplett & Scott’s firearms belong in any U.S. military firearms collection, particularly one that concentrates on patent breechloaders. Today, the 30” rifle is more commonly found than the 22” carbine. Antique firearm expert Norm Flayderman once noted, in his section on the Triplett & Scott Company, that the carbines are “quite scarce and will bring approximately 20% premium over the values listed.”

Overall, the Triplett and Scott firearms, both the rifle as well as the carbine, were well-made with blued barrel, case-hardened steel, complete with a oil-finished walnut stock. The "round-the-shoulder" illustration of the magazine on the patent drawing was discarded on the production model, but the initial patent illustration spawned the curious sling-swivel assembly. It seems a short strap was used that reached from one swivel to the other, enabling the bearer to carry the piece suspended under the arm in a ready-to-fire posture.

Aside from the Dec. 22, 1864 testing, the Triplett & Scott breechloaders appeared in trials in 1865 and again in May 1866. Of the 65 guns undergoing testing, five were chosen, but Triplett and Scott’s repeater was not one of them. In 1872, Triplett & Scott’s repeater submitted their firearm to the Ordnance Board testing. There were 108 entrants, 10 of them repeaters, but resulted in nothing but goose eggs for Triplett & Scott.