This article was originally published in American Rifleman, September 1998

Jeff Cooper’s dream of a modern, “general purpose” rifle suitable for the rifleman, big-game hunter, soldier on a long-distance mission or law-enforcement officer is now a Steyr factory-made reality. Now, almost two decades later, the Scout's price is lower than when introduced, at about $1,500.

By Mark A. Keefe IV, Managing Editor

Scout (skaut) “2. Mil. One sent out ahead of the main force in order to reconnoiter position and movements…One sent out to obtain information. 3. One who keeps watch…v.1 To act as a scout…to travel about…” – The Oxford English Dictionary

There is but one reason for Steyr’s new Scout rifle as it is today, and that reason goes by the name of Jeff Cooper. Never bashful about his ideas, the forthright and sometimes-controversial Lt. Col. Jeff O. Cooper some 15 years ago began to call for a new rifle concept based on “ruggedness, versatility, speed of operation” and practical accuracy while stressing the need for the rifleman to hit on the first shot. Whether you agree with Jeff Cooper, or his Scout rifle ideas or not—and quite a few do not—is immaterial, as his theory is now a factory-made reality.

Cooper himself defined the concept of the “general purpose” or “Scout” rifle in these pages back in September 1985: “A general-purpose rifle is a conveniently portable, individually operated firearm capable of striking a single, decisive blow on a live target of up to 200 kilos in weight at any distance at which the operator can shoot with the precision necessary to place a shot in the vital area of the target.” In essence, the Scout rifle would be the one rifle to handle most applications from varmints up through larger North American big game.

There were several conferences held at Paulden, Arizona’s Gunsite Training Center beginning in 1983 to “examine the subject of modernization of rifle design.” The guidelines stated that the new rifle be 1 meter in length and have “a weight limit of three kilos” (6.6 lbs.) unloaded with the scope and other accessories in place—these criteria mandated a short-action and short barrel. The Scout should also have an integral, retractable bipod, a long-eye-relief scope mounted forward of the receiver ring, reserve iron sights, a practical and useful sling, and a cartridge trap in the buttstock.

During the intervening years, there have been Scout prototypes, based on Remington, Ruger and Sako actions, that are beyond the scope of this article. Suffice to say Cooper and his fellow Scout rifle enthusiasts refined the concept over the intervening years, and, just last year Steyr-Mannlicher, Ges. m.b.H., unveiled a factory-made production Scout Rifle made in cooperation with Cooper.

I caught up with the living legend among gunwriters one night at the 1998 NRA Annual Meetings in Philadelphia. When I asked for a few minutes of his time to talk about the Scout, his enthusiasm for the rifle shined through, and despite the late hour, we sat down to discuss his concept as manifested in the factory-produced Steyr Scout.

Why Steyr? Well, one of the progenitors of the whole concept was the handy little 6.5 mm Mannlicher carbine dating from the pre-World War II era. And, more importantly, because the Austrian gunmaker would listen when other manufacturers would not, Cooper said. “The Scout is a radical concept, and [the larger American makers] didn't want to take the chance.” He stressed, “The concept is misunderstood ... and most objections are from traditionalists who think a rifle should look a certain way. And the Scout is not traditional. It is a radical departure,” He was quick to point out, “the concept is mine— the execution is theirs.”

Gun South Inc., Steyr's importer, last year held a writer's conference at the NRA Whittington Center in Raton, New Mexico, to introduce prototypes of the Steyr Scout Rifle—the gunwriters' response was overwhelmingly positive. We at American Rifleman prefer to evaluate production rifles and eagerly awaited the first production Scout, which is little different from the prototypes except in a few stock cosmetics and the top rail dimensions.

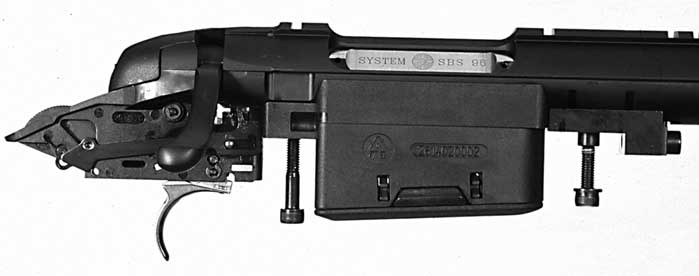

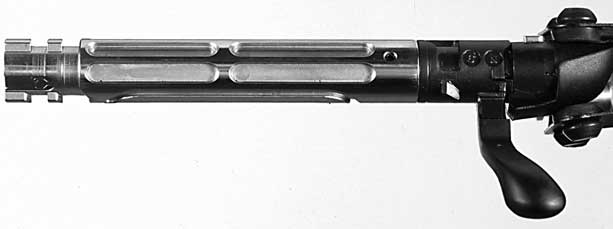

The heart of the Scout is Steyr's bolt-action SBS (Safe Bolt System) short action. The SBS has a full-diameter bolt whose body and lugs are the same .825" diameter. The bolt head measures .636" in diameter, has a recessed face and employs four lugs arranged in two 180 degree opposed rows in the bolt head, giving the SBS a 90

degree bolt lift.

The two rear lugs are shorter than the front set. The bolt also employs an internal, plunger-type ejector on the left side and a spring-loaded claw extractor on the right that is about .19" wide. The bolt handle is the familiar, flat Steyr butter-knife shape, and an indicator pin protrudes from the bolt shroud when the firing pin is cocked. Many of the rifle's other components—including the bolt shroud—are of lightweight polymer to save weight. The Scout's bolt differs from the standard SBS in that it has lightening cuts throughout its body designed to make the requisite 6.6 lb. cutoff—which, at 7 lbs, 5 ozs., it misses.

The Scout employs an aluminum receiver mated with an aluminum extension forward of the typical receiver ring location that together extend atop three-quarters of the fore-end'slength. A Zytel cap or “barrel extension housing” is just forward of the extension, and the adjustable front sight unit is housed there. The bolt locks into a barrel extension or “barrel locking bushing” as it is called by Steyr, rather than into the receiver. This allows the use of the lighter metal for the receiver—which no longer is subjected to as much as stress on firing—as the barrel locking bushing and its safety bushing are of steel. The latter bushing completely surrounds the extractor, giving the shooter an extra safety margin in the event of a case failure or pierced primer.

The rifle’s minimum dimension ejection port, another Steyr hallmark, also impedes entry of dirt, twigs, etc., while enhancing receiver rigidity—but makes single-loading of cartridges more problematic. The action is held to the stock at the rear by two stock bolts that are pillar-bedded. At the front, a polymer pin secures me barrel-extension housing to the fore-end. It is only visible when the bipod is in the down position.

The 19" barrel is a traditional Steyr cold-hammer-forged steel tube that is fluted for 6 ½” forward of the fore-end starting 1/2" back from the muzzle. The four-groove rifling is 1:12" with a right-hand twist. The muzzle crown is recessed to protect the rifling origin.

A Weaver-style rail system is integral with the top of the receiver and its extension for mounting die supplied Leupold M8 2.5X Intermediate Eye Relief Scope to Demounted in the Scout position. The supplied rings are numbered to each rifle and the Leupold scope is installed at the factory. Those who don't favor the Scout scope may mount a glass of their own choosing in the more familiar position above the action port, as the rails extend behind the action port.

The lightweight, synthetic stock's design is very unconventional, but extremely practical and makes handling quite quick—another important trait of the Scout concept. It is constructed of durable gray Zytel with black inserts in the buttstock and fore-end. The rearmost insert carries Cooper's "JC" logo. Length of pull is adjustable from 12.68” to 16” through the use of removable .45”spacers. Two are supplied and others are available at extra cost. There is a storage compartment for extra ammunition or cleaning supplies in the hollow stock just forward of the magazine well in the butt. Access to it is gained by depressing its latch inside the magazine well.

What appear to be panels on either side of the fore-end are actually the legs of the Scout's cleverly designed bipod. They fold compactly into either side of the fore-end and are freed by depressing a release at the rear of the accessory rail. Each leg is pulled down until it locks into position. Folding is accomplished by simply pulling the legs back to the rear, though it may be necessary to depress the release for the unit to engage its retaining tabs and fold flush back into the fore-end. Some have commented on the perceived “flimsiness” of the bipod, fearing it is sure to break. In my experience it held up well, did its job and showed no signs of strain, though the “snap” of it unlocking is a bit disconcerting. Remember, this is not Harris’ excellent bipod, meant to be used all the time, but is an unobtrusive, light, field bipod that is always there when you need it.

The Scout employs the SBS's excellent three-position safety located in the tang. When pressed all the way forward, it is disengaged and a red dot is shown. When in intermediate or "loading" position, a white dot is visible at the top of the ribbed safety button, the sear is blocked and the bolt may be manipulated. In its rearmost position, too, a white dot is visible, the sear is disengaged and the bolt is locked in position. A spring-loaded, gray plastic button pops up and prevents the safety from being pushed forward to the "off' or "loading" position unless it is first depressed. This position also acts as a bolt release. Opening the bolt and moving the button to this position allows the bolt assembly to be withdrawn to the rear.

The standard magazine is a five-round, double-column, detachable box made almost: entirely of black polymer. Depressing tabs on either side of the box simultaneously, allows the magazine to be removed or moved to the “cut off” position. There are two positions for the magazine catch. The first is flush with the bottom of the stock, allowing the Scout to be fed from the magazine, and the second fixes the magazine ¼” lower, which prevents the bolt from stripping the top cartridge from the magazine. This frees the shooter to be able to fire single shots while keeping the magazine “topped-off,” as with the Model 1903 Springfield and No. 1 Mk. III Lee-Enfield, and kept in reserve for emergencies. A spare magazine may be carried in the bottom of the buttstock, and a 10-round conversion unit is also available.

The Scout is supplied with an eminently practical, three-point sling designed by Eric S. Ching. The black leather sling is attached by Millet T-swivels at the butt and at the fore-end on the sides forward of the magazine well. There are attachment points for it on the latter two swivels on both sides of the stock, making the sling convenient for southpaws. I found the Ching sling to work well in the field, being easy to get into quickly and supporting the rifle steadily.

Frankly, the Scout is a radical concept for most American riflemen. Speaking as one who finds a pre-'64 Model 70 with a modern 3-9X the penultimate, the Scout lakes some getting used to. But just because it's different doesn't make it bad. It's not hard to appreciate a well-made, lightweight, handy and accurate rifle with storage in the stock. The bipod is novel, but you can ignore it if you so choose. Where many get hung up is on the Scout scope. What it conveys is the ability to get on target very quickly and keep both eyes open and on the target and what is going on around it. With practice, it is easily mastered, and some even prefer it to the standard mount position after trying it. What it forfeits, however, is magnification. But, as Cooper told me with a slight grin, “A Scout scope does not a Scout rifle make.” Perhaps the colonel has some converts he doesn't know about yet.

As a matter of fact, if Cooper had everything his own way, he would eliminate internal windage and elevation adjustments entirely and make those adjustments with the mount system. Scopes are complex instruments and, with even the best of them, there is potential for something to go wrong. “Experience in Africa has taught me you only need one rifle, but should bring two scopes,” he said. Sound advice. That's why the Scout has flip-up front and; rear “emergency” sights. The rear is an elevation-adjustable aperture and the front isa windage- and elevation-adjustable flip-up ramp with a white vertical line.

The Scout Rifle was fired for accuracy with the results shown in the accompanying table, and function-fired with mixed Federal , Hornady, PMC, Remington, Samson and Winchester ammunition. We mounted a 10X Redfield in the conventional position above the action port to wring out the accuracy potential of the Scout, then fired the same Winchester 168-gr. load with the supplied lower-magnification Leupold Scout 2.5X Scope to demonstrate the difference in accuracy when shooting with the more practical forward-mounted glass. There were no failures of any kind, and loading and firing during our tests were flawless. Accuracy was impressive considering the lightweight barrel. I could not discern any falloff in accuracy after rapid firing, even though the barrel heated up considerably. As befits a rifle weighing only 7 lbs. 5 ozs., recoil was stiff with heavy loads, though the ergonomic stock design and rubber buttpad did help tame it. There was also considerable muzzle flash with some loads due to the Scout's abbreviated barrel.

, Hornady, PMC, Remington, Samson and Winchester ammunition. We mounted a 10X Redfield in the conventional position above the action port to wring out the accuracy potential of the Scout, then fired the same Winchester 168-gr. load with the supplied lower-magnification Leupold Scout 2.5X Scope to demonstrate the difference in accuracy when shooting with the more practical forward-mounted glass. There were no failures of any kind, and loading and firing during our tests were flawless. Accuracy was impressive considering the lightweight barrel. I could not discern any falloff in accuracy after rapid firing, even though the barrel heated up considerably. As befits a rifle weighing only 7 lbs. 5 ozs., recoil was stiff with heavy loads, though the ergonomic stock design and rubber buttpad did help tame it. There was also considerable muzzle flash with some loads due to the Scout's abbreviated barrel.

As of this writing, the only caliber offered in the United States is .308 Win. and the only stock color is gray—though 7mm-08s are offered in European nations that prohibit civilians from owning “military” caliber firearms. GSI advises that two patterns of Realtree camouflage are in the works for 1999 as well as some other options.

Virtually everyone I have spoken with about the rifle enjoyed handling it. And those few minutes' handling even won a few converts. The rifle was extremely handy, coming quickly and naturally to the shoulder, and it balanced on the magazine floorplate. The overall workmanship of the rifle, too, was excellent—as should be expected with a rifle in this price class.

And price—a hefty $2,595 suggested retail—may be the rifle's only serious drawback. That includes the Leupold scope and mounts, but it is still rather high. The engineering and concept behind the gun, however, may make the price tag a little more digestible. Steyr calls the Scout “The One Rifle,” as it is designed to fulfill roles that many shooters have two or more rifles to fulfill. It can be a mountain rifle, a tactical rifle, a hunting rifle and a ranch rifle. Whether the Scout's appeal will be limited to well-heeled Cooper devotees, only time will tell. I can't help but think that the gun will find more general acceptance among typical riflemen who can appreciate its impressive array of traits. For those who aren't scared by the Scout's “sticker shock,” it represents solid value.

“At such time as all the proper instruments have been completely assembled,” Cooper penned in these pages in 1985, “there will be an opportunity for a forward-looking manufacturer to take advantage of modern technology and make a great leap forward for the rifleman.” When I asked what he thought of Steyr's Scout, Cooper replied with obvious pride in his voice, “It's just fine.”