This article was first published in American Rifleman, June 1989

Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Conan Doyle both witnessed the lethal fire that Boer farmer-riflemen rained on British troops in 1899. They returned home to promote civilian marksmanship through the expansion of rifle clubs in England.

By Philip Bourjaily

The civilian rifle club movement in England grew out of the disasters of the first months of the Anglo-Boer War late in 1899. The British Army suffered a series of reverses at the hands of outnumbered civilians unlike anything the nation had witnessed in the prior years. One of the shocking revelations of the war was the poor standard of marksmanship in the army compared to that of the Boers. The Boers grew up hunting and riding; each burgher provided his own horse and rifle when he joined his commando. These expert game shots, partial to the bolt-action Mauser repeater, took a heavy toll on British troops often ordered to advance in long lines as if fighting lightly armed tribesmen.

Two men who would later found rifle clubs early in the movement were among the many who followed the course of the war with great anxiety: Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Conan Doyle.

Kipling, the poet laureate of the British Army, was appalled to read in the papers how the regulars he had glorified in his stones and poems were mauled repeatedly by a handful of farmers. He tried to help on the home front, first by a failed attempt to start a volunteer company in the resort town of Rottingdean where he lived, then by writing “The Absent Minded Beggar.”

The poem was critically reviled but extremely successful in its purpose of raising money for the wives and families of soldiers serving in South Africa. Finally on Jan. 20, 1900 Rudyard Kipling left for Cape Town to see the situation firsthand.

Sherlock Holmes creator Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle had been turned down by the Middlesex Yeomanry when he applied for a commission early in the war, but he was subsequently offered a position on the staff of a private field hospital due to leave for the front in the spring of 1900. In the intervening months, Conan Doyle experimented with an idea: since the Boers often fought from trenches, why not drop bullets on their heads via “high angle” rifle fire? Conan Doyle made and tested a prototype high angle sight and wrote several letters to the War Office promoting his idea, which was rejected as impractical.

The tide of the war had already turned in favor of the British when Conan Doyle arrived at Lord Roberts' headquarters in the city of Bloemfontein on April 2, 1900. Kipling, who had just spent six weeks working on the staff of the military newspaper The Bloemfontein Friend, returned to Cape Town on April 3. Although the two authors were mutual admirers and casual friends— Conan Doyle had been a house guest of the Kiplings in Vermont in 1894—apparently they just missed one another in South Africa.

Dr. Conan Doyle and the staff of the Langman Hospital were soon swamped by a massive outbreak of typhoid fever among the troops after the Boers cut off the city's fresh water supply. Nevertheless, Conan Doyle found time to go briefly into combat with the army during its advance on the town of Brandfort. He was as impressed with the scale of the modern battlefield and the range of the weapons as Kipling had been when he witnessed the battle of Karee Siding in March. At one point during the fighting, Kipling wrote: “… [we] move[d] forward to the lip of a large hollow where sheep were grazing. Some of them began to drop and kick. ‘That's both sides trying sighting shots’ said my companion. ‘What range do you make it?’ I asked. ‘Eight hundred at the nearest. That's close quarters nowadays. You'll never see anything closer. Modern rifles make it impossible.’”

Although the Boer War offered firsthand proof to the British that accurate rifles had changed the nature of warfare, a tremendous enthusiasm had surrounded the rifle since the authorization of the volunteer rifle companies in 1859. The volunteers, a Victorian fad for amateur soldiering, were popularized by periodic rumors of a French ironclad battle fleet. The National Rifle Association of Great Britain was founded in 1859 as well, to promote a national taste for rifle shooting and thereby sustain interest among the volunteers between invasion scares. The association's stated aim was to make the rifle “what the bow was in the days of the Plantagenets”--a national weapon. For the history-conscious Victorians, the parallels between the rifle, a weapon requiring far more skill and practice than the smoothbore musket it replaced, and the longbow, were irresistible.

“’What the 'clothyard shaft and grey goose-wing' effected, when guided by an English eye and an English hand at Crecy and Agincourt, the rifle bullet will do in any future contest …” wrote Hans Busk in The Rifle and How to Use It. The London Times went so far as to editorialize: “The change from the old musket to the modern rifle has acted on the very life of the nation, like the changes from acorn to wheat and stone to iron are said to have revolutionized the primitive races of men.”

Despite the NRA's best efforts during the previous 40 years, the war in South Africa demonstrated clearly that England was not yet a nation of marksmen. In May 1900 Prime Minister Lord Salisbury called for the formation of civilian rifle clubs to redress the shortcoming. In a speech to the Primrose League, he stated his goal was no less than that “a rifle should be kept in every cottage in the land.” In response the NRA formulated its guidelines for the affiliation of civilian clubs. Ninety-two were formed that first year, among them Rudyard Kipling's club at Rottingdean and Arthur Conan Doyle's Undershaw Rifle Club.

Kipling had returned home to Rottingdean convinced that the English people had grown too soft and complacent to defend their empire. Not only had the regular army had a difficult time with the Boers, it had compared poorly to its colonial allies; the Australians and New Zealanders had adapted easily to the irregular warfare of their opponents. Kipling was then at the height of his fame and popularity, and he was determined to use his status as a platform for moral leadership, both through his writing, and in the summer of 1900, by example.

The first task facing Kipling as he started the rifle club was in many ways the most difficult: securing space for a 1000-yd. range. On a small island nation such space was at a premium; even the royally supported NRA had been forced to move its annual meeting from Wimbledon to Bisley when stray bullets began striking the Duke of Cambridge's property. Nothing less than a full-size range would do for Kipling, however, and in July he was able to write to his American friend Dr. James Conland: “…the bulk of my efforts have been in trying to get a rifle range over these open downs. At last I think I have succeeded and after untold bothers the landowners have given their consent to our putting up targets and butts. It was a weary business corresponding with lawyers and. land-agents and generally making oneself agreeable to everyone—but now (that] we have started a village rifle club I begin to see a reward for my labors.”

It was not the Boer War that motivated Kipling but the continental war with Germany that he already foresaw. He threw himself into club activities, serving as president, personally paying for new targets to replace the old windmill type, presenting the club with a Nordenfeldt gun that had been used in South Africa and taking his turn as musketry instructor, familiarizing club members with the .303 Enfield service rifle. “[M]y real work this summer has been connected with our new rifle range,” he wrote to Dr. Conland in December. “The men are just as keen as can be and turn up every week to put in their firing. Can you imagine me in corduroy clothes and a squash hat with the Club ribbon around it in charge of a firing party of four on the ground; an hour of standing over the rifles with one eye on the targets arid the other on the men (Some of 'em have queer notions about shooting).”

President Kipling oversaw the construction of a drill shed for winter training. Although Kipling spent the winter of 1900-01 in Cape Town, the instructions he left behind testify to his seriousness about the club's activities:

Instructions for the use of shed during my absence:

“Men to have two evenings a week for MT (Morris Tube) practice and such other evenings as the Sergeant shall see fit for

“Gardner Gun Drill

“Signalling

“Guard Drill, etc.

“Boys to have two evenings a week. One for MT practice and one for gymnastics.

“Boys evenings are not to be Monday and Wednesday.

“Men and Boys evenings to be kept Separate.

“Men to be instructed in gym work if Sergeant thinks fit.

“Fatigue parties must be told off to clear up the shed, every night as there will be no allowance for caretakers.

“All damage must be paid for by offender.

“The Rifle Club may hold meetings and concerts in the shed under Sergeant's supervision. No intoxicating drinks under any circumstances.

“Smoking is permitted.

“Cst. Gd. Wells is to be in charge of the Gardner Gun with right of way and free entry into shed for that purpose.

“--Rudyard Kipling”

Arthur Conan Doyle drew a different lesson from the Boer War than did Rudyard Kipling. Recognizing the English peoples' aversion to conscription, and opposed to compulsory service himself, Conan Doyle saw the war as proof that civilian marksmen could effectively resist invasion. He founded the Undershaw Rifle Club and explained his purpose in a letter to the Glasgow Evening News entitled “Burghers of the Queen” in December of 1900. Conan Doyle wrote: “… the idea I am working with is simply riflemen drawn from the resident civilians. The men are quite eager to pay for their own cartridges which, with the Morris Tube system, can be sold at three for a penny. I made ranges for them at 50, 75 and 100 yds., the latter representing 600 yds. without the Morris Tube system… on Holidays I will give them a prize to shoot for ... the whole expense of targets (5), mantlets, rifles (3), with tubes is not more than £30.”

For the pragmatically minded Conan Doyle, the “miniature” or .22 rimfire smallbore range seemed a more practical solution to the problem of space than a full-size 1000-yd. range like the one at Rottingdean. (The Morris Tube was a barrel insert for the service rifle that allowed it to chamber the .297/.230 short or long, a center-fire equivalent of the .22 rimfire.)

Conan Doyle further proposed that all men between the ages of 16 and 60 (not coincidental the age limits for Boer soldiers) should train in rifle clubs. Those reaching a certain level of proficiency would be awarded a distinctive broad-brimmed hat and a rifle and bandolier to keep at home, a “uniform” remarkably like that worn by the Boers.

When the military correspondent for the Westminster Gazetteer criticized his ideas, Conan Doyle responded: “I have stood all day today marking for our own corps of civilian riflemen. Gentlemen, shopboys, cabmen, carters and peasants were all shooting side by side. The prize, at a range which was equivalent to 600 yds., was taken by a top score of 83 out of 90; 82, 81 and 80 were next. Fifty men spent their bank holiday at my butts, and the scene was like a village competition in Switzerland. Conceive the stupidity that would refuse military material such as that when all it will ever ask of its country is a rifle and a bandolier!”

By January 1901, Conan Doyle was ready to pronounce the club a success, and he wrote to the local paper, the Farnham, Haslemere and Hindhead Gazette: “I hope to see similar clubs started at Headley, Churt, Tilford, Witley, Chiddingfold and especially at Haslemere. If any gentleman desires to organize one, and so help in what is a very urgent public duty, I will be happy to furnish him with full information as to the methods by which we have brought our own success.”

At the end of that summer, Kipling also had reason to be pleased with the results of his work. He wrote again to Dr. Conland; “…the end of the season shows we have forty very fair shots and about thirty men who at least know something of shooting. We've won every match so far (six in all) that we've shot against outside teams; and some of the teams were fairly strong ones.”

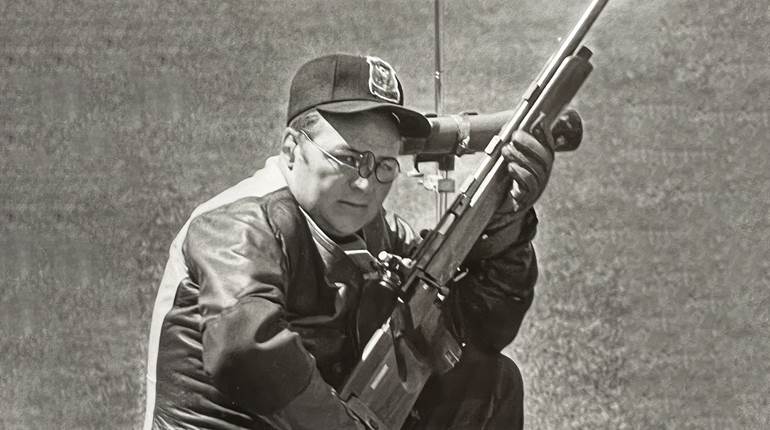

Unfortunately, we have no better account of Kipling's marksmanship other than that he shot "adequately" despite his poor eyesight and that he scored a bullseye at the opening ceremonies of the Winchester Drill Hall. He was, however, a fierce competitor, shooting in all of the club's matches, serious to the point of surliness. When a member of the visiting Newhaven Volunteers expressed his interest in meeting the great man at a match in Rottingdean, Kipling snapped “Well, now you can see the animal on his own ground.”

Kipling eschewed special treatment, insisting that everyone must “muck in together” in the important business of preparing for war. Unfortunately his celebrity drove him away from the resort town of Rottingdean and the rifle club. Curious sightseers continuously invaded his privacy, and a local tour bus line made his house one of its most popular stops. Late in the summer of 1902, the Kiplings moved to a house in the country. The Islanders was published shortly thereafter. In the scathingly sarcastic poem, Kipling made plain his scorn for the English people he felt would rather play games than prepare for war, and ridiculed the Duke of Wellington's notion that wars were won on the playing fields of Eton:

“Will ye pitch some white pavillion and lustily even the odds

“With nets and hoops and mallets, with rackets and bats and rods?

“Will the rabbit war with your foeman— the red deer horn him for hire?

“Your kept cock pheasant keep you— he is master of many a shire

“Arid, aloof, incurious, unthinking, un-thinking, gelt

“Will ye loose your schools to flout them, till their brow beat columns melt?”

Kipling's proposed solution was simple and true to form:

“Each man born to the Island, broke to the matter of war

“Soberly and by custom taken and trained for the same

“Each man born to the Island entered at youth to the game

“As it were almost cricket, not to be mastered in haste.”

Although by then Kipling's hands-on work with the rifle club movement had ended, he continued to support any cause that he believed would promote strength and readiness. He wrote the “Patrol Song” for Boer War hero Baden-Powell's newly formed Boy Scouts and spoke out on behalf of the National Service League's efforts to implement conscription. “The Parable of Boy Jones,” written by Kipling in 1910 for The Rifleman, official organ of the Society of Miniature Rifle Clubs, gave a detailed fictional account of rifle club shooting indoors and out.

Arthur Conan Doyle, knighted in 1902 for his wartime service as a doctor and two books, The Great Anglo-Boer War and The War in South Africa: Its Cause and Conduct, left the healthy Undershaw Rifle Club in other hands and turned his attentions elsewhere. In 1905, however; he was prompted to write again on the subject of miniature rifle clubs in support of Lord Roberts, who had become the president of the Society of Miniature Rifle Clubs.

Writing to the London Times in June 1905, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle presented his case, making the inevitable comparison to the Middle Ages: “The first point which is worth insisting upon is that a man trained at a miniature range (whether Morris Tube or otherwise) does become an efficient shot almost at once when he is allowed to use a full range. What with the low trajectory and absence of recoil in a modern rifle the handling of the weapon is much the same in either case. I am speaking now of an outdoor range where a man must allow for windage and raise his sights to fire. It was skill at the parish butts which made England first among military powers during the fourteenth century. My suggestion is that the parish butts be restored in the form of the parish miniature range.”

The renewed appeal helped to bring about a large increase in the number of rifle clubs. By 1906 there were 302 miniature and 307 full-range clubs affiliated with the NRA. The government forgave the excise tax on firearms purchased for all but sporting use, and the Conan Doyle Cup was presented by Dr. Langman of the Langman Hospital to be shot for with: the miniature rifle at Bisley. The rifle club movement peaked during the years 1914-18 with more than 1,900 affiliated clubs, most of them miniature clubs.

At the beginning of the Great War, Lord Roberts wrote in his president's message to the Society of Miniature Rifle Clubs: “Proud as I am of rifle clubs I shall be prouder still if, when the war is over, it can be said they helped to win the victory we know is certain.” It is difficult to judge what effect the membership of 1,900 clubs may have had in a war that ultimately saw 5.7 million men serve in the army.

Before the end of the First World War, Kipling already warned of a second war with Germany. Although subsequent events proved Kipling right, the aftermath of the “War to End All Wars” saw instead an understandable spirit of pacifism and a corresponding drop in rifle club activity. The government, alarmed by acts of postwar violence and the large number of surplus weapons brought into the country, reversed its previous course of encouraging the private ownership of rifles and passed the Firearms Control Act of 1920. In 1938, on the eve of the Second World War, only 471 rifle clubs remained.

The author wishes to thank members of the Kipling Society who were kind enough to help him with his research.