Back when most of the hunters I knew used “primitive” arms, such as M1903 Springfields and 4X scopes, the variable riflescope was just starting to be accepted. This was in the mid-1960s. Most shooters still think of variables as a “modern” development, even though Zeiss (who else?) first began marketing practical riflescopes that would change magnification back in the 1930s.

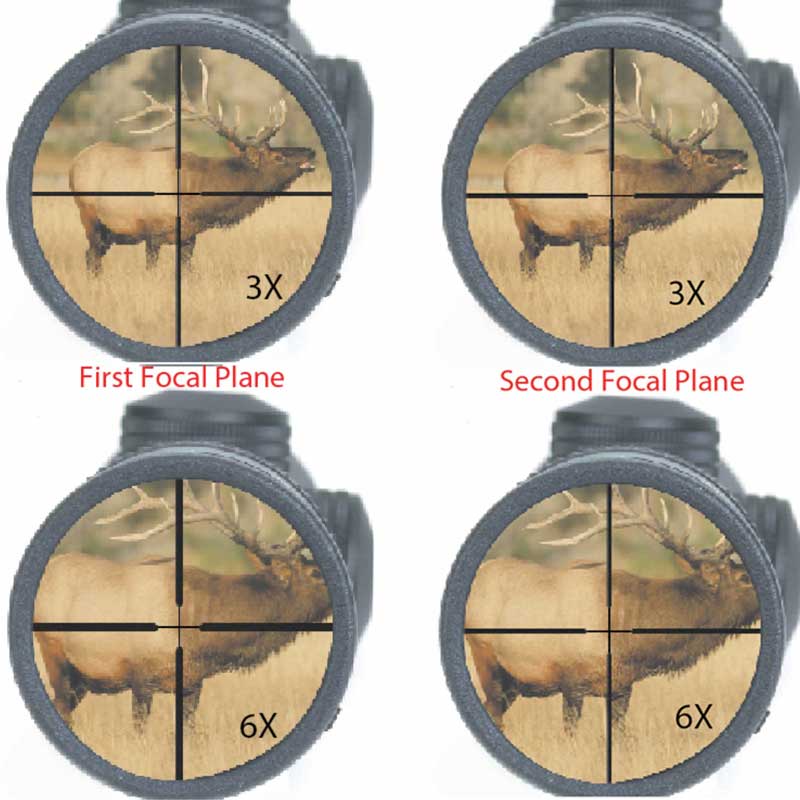

These first variables were delicate and complex, and they featured what is called a first-focal-plane reticle. The first-plane reticle supposedly has one virtue and one vice. When the magnification in first-plane scopes changes, the point of impact never shifts—but the size of the reticle appears to grow and shrink even though it remains proportional to the target. This may not sound like too big of a deal, but in big-game hunting a crosshair that looks just right a 5X looks like a rope at 10X or shrinks to a fine blond hair at 2X.

Even in the early days of variables, optical engineers knew a solution to this problem, but first-plane reticles were used for decades because the solution didn’t work with the manufacturing methods of the time. To understand the solution, we need to understand how a variable scope works.

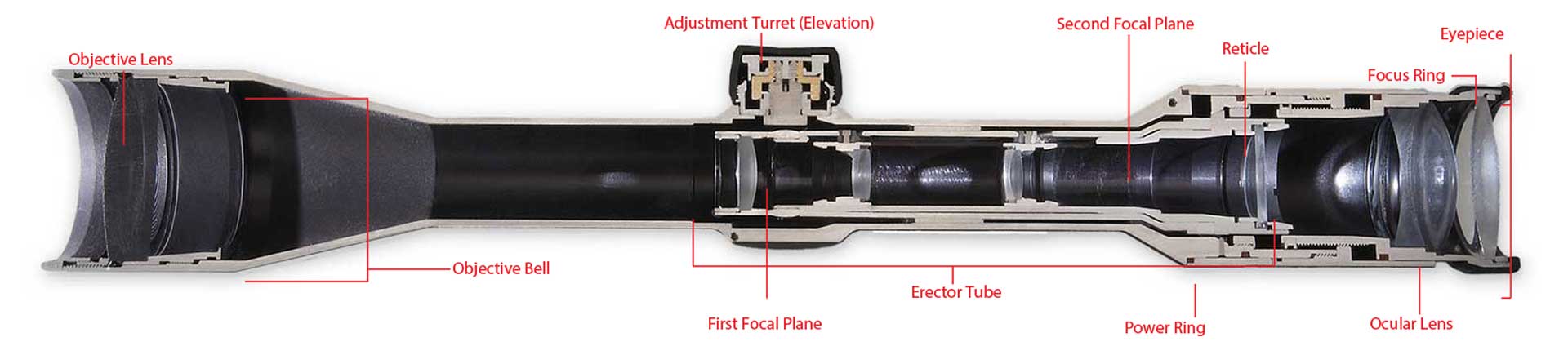

In a fixed-magnification scope, the erector lenses are held inside a stationary tube. In variable scopes, this tube slides back and forth, cammed by the turning of a ring on the outside of the scope. The reticle can be placed in two locations: between the objective (front) lens of the scope and the power-change tube, or between the power-change tube and the ocular (rear) lens.

When in the first-focal-plane (in front of the power-changing mechanism), the reticle is magnified along with the image, and its size and position relative to the target don’t change. When the reticle is placed in the second-focal-plane, behind the power-changing mechanism, its apparent size stays the same—but point of impact can shift if the power-change tube doesn’t slide precisely back and forth along the same axis in the center of the scope.

Early on, making a second-plane scope work precisely would have involved careful hand-fitting of each scope, and so was simply too expensive for mass manufacture. To cope with the growing and shrinking first-plane reticle, most European scopes featured a set of three or four heavy posts converging on a fine, center crosshair, while America’s Bausch & Lomb scopes used a finely tapered reticle actually etched on glass.

European hunters preferred first-plane reticles. They hunt a lot at night, when the better twilight factor of higher magnification is an advantage. When they turn their scopes up, the reticles look heavier, a real advantage when aiming at a wild boar in a moonlit meadow. But Americans saw variables not as aids to night aiming, but as all-around scopes. With a twist of the wrist, a 3-9X scope would be perfect for everything from elk in the timber to long-range varmints. Consequently, hunters wanted a reticle that could quadrisect a woodchuck’s head at 9X but stand out plainly in dim woods at 3X.

So American manufacturers started working with second-plane scopes until they got it right. Redfield, I believe, was the first to solve the problem back in the late 1950s—the reason variable scopes suddenly became popular in the 1960s. But in the last 20 years, computer-driven machinery has made second-plane variables essentially foolproof, even in relatively inexpensive scopes.

So why do some American hunters buy first-focal-plane scopes? It turns out first-plane scopes have one other virtue: The reticle’s constant size in relationship to the target makes using the reticle as a rangefinder much easier. More hunters are hunting whitetail deer than ever before and under conditions that make first focal-plane scopes advantageous. Under the intense pressure of longer seasons and more hunters (just take a look at any magazine rack and count the deer-hunting titles), the whitetail has become by far the most nocturnal big-game animal on this continent.

Modern deer hunters realize that more magnification helps them see better during those twilight hours when deer move, but at high magnification many second-plane reticles disappear shortly after sunset while first-plane reticles grow more visible. Essentially, we’re finding that our European cousins knew something useful about variable scopes all along.

Despite all that, the second-plane scope remains the top choice among American hunters, something recognized by the more intelligent European manufacturers, which usually market a line of special “American-style” scopes with 1” tubes and second focal plane reticles. The reason they do this is that most American hunters still see variable scopes as multipurpose instruments or, these days, as extremely precise long-range aiming devices in which a finer reticle works better.

Testing Riflescopes

A several decades ago, many writers thought variables were inferior to fixed-power scopes. Variables were heavier, fell apart easier, changed point of impact and, because of the compromises inherent in moving lenses, were optically inferior. You still see these charges made sometimes.

These days, it’s rare to find even the cheapest bubble pack 3-9X showing any significant change of impact. Though in the very cheapest scopes a fixed-power might be more rugged, many manufacturers produce inexpensive variables specifically for shotgun use. After all, a light slug gun’s recoil is tougher than any rifle short of a .375 H&H. The first variables needed to be extra long and heavy, which helps in keeping the view sharp through big changes in magnification. But back then we didn’t have the marvelous optical glass we have today, or computerized design programs.

These days, you can buy a 3-10X scope that’s only a couple of ounces heavier than the typical 4X scope of the 1950s, and the smaller variables can be even lighter than those old 4Xs. They’re also brighter. Though the very finest fixed-power scopes are still slightly brighter than the best variables (a by-product of the fewer lenses in fixed-power systems), the difference is very slight and is offset by the higher twilight factor of big variables. Sure, a fixed 6X will be slightly brighter than a 3-10X variable of the same make set at 6X. But crank the 3-10X up and you’ll be able to see more under all but the darkest conditions. In North America, real darkness occurs after legal shooting hours.

In practical terms, because most scope manufacturers sell far more variable scopes than fixed-powers, variable optics tend to be better. In my experience fixed scopes that feature single-coated lenses simply aren’t as bright as its multi-coated ones I've sampled. For comparison, I tested a plain old 4X Leupold against the company's older 1.5-5X Vari-X III. In theory, the 4X should be brighter. It’s got a bigger 28 mm objective versus the 20 mm of the 1.5-5X, providing an 8 mm exit pupil—far larger than the 1.5-5X’s 4 mm exit pupil. It also has fewer lenses than the variable, cutting down on light loss on each lens surface. However, because of multi-coating, the little variable is just as bright, if not brighter, and provided a much clearer view when looking toward the sun. Both scopes weigh about the same, a little more than 9 ozs., though the variable is slightly trimmer.

Despite all that, you can run into occasional problems with variable scopes. Most can be prevented by three simple tests. First, turn the magnification ring. It should not turn easily, and the rings on better scopes turn harder. There’s a simple reason for this: a closer fit of all moving parts. This is desirable in variable scopes since any slop in the erector tube can mean a shift in point of impact.

You may have to buy the scope for the next two tests, but if the scope fails either, the manufacturer should replace it. First, mount the scope and place the rifle in a vise so that the reticle rests on some object 100 or 200 yards away, or slip a collimator into the muzzle. Then look through the scope and turn the magnification ring. The reticle should remain on the same aiming point, either across the street or on the collimator grid, through the scope’s entire range of magnification. If there’s any shift, the scope’s defective and the manufacturer should replace it. (It also might behoove you to perform the same test while turning a big scope’s adjustable objective. Once in a while, you’ll find a reticle shift there, too. This is caused by the lens being cockeyed.)

Last comes a dunk test. Variables do have an extra hole through their body, the slot cut for the camming stud on the magnification ring. In theory, this leaves more chance for water to get inside the scope. (I’ve never had it happen on a quality scope, but why not make sure?)

What should impress you after you’ve performed these tests on several scopes is how rarely modern variables show any significant reticle shift or leak around the power ring. In all the testing I’ve done in the past half-dozen years, I have found only one scope with any significant reticle shift, and have never found one that leaked around the power ring. During that time I’ve tested at least 100 variable scopes.

The only real problem I’ve seen with modern variables might be termed “inappropriate use.” This comes from mounting too big a scope on too powerful a rifle. Big variables (from 4-12X up) tend to unravel, particularly in the erector tubes, if you insist on mounting them on hard-kicking big-game rifles from .300 magnum on up. This is becoming more and more the style, however, as some hunters seem determined to shoot at any animal they can possibly see.

Personally, I have no real use for a .30-378 Wby. Mag. or a big-game scope topping out at more than 10X, but if you do, then buy the very best scope that you can. Even then, try to find the lightest scope available. Extra weight means extra inertia when the big gun recoils. If you buy good scopes and make them smaller as the guns get bigger, you’ll rarely have a problem. Most of the problems I see and hear of occur with .300 magnums of all sizes and scopes larger than the popular 3-10X.

Above .30 caliber, most hunters seem content with small variables, perhaps because .338s, .375s and .416s are usually used on larger animals, while many .300 magnum shooters are after the ultimate long-range pronghorn, sheep and deer rifle. But those breakdowns are rare occurrences, caused by pushing the rifle/scope package to the limit. For most hunters, modern variables are even more reliable, in every way, than the 4X scopes our fathers and grandfathers used.

All that said, why would anyone choose a fixed-power scope? I do myself, and often. About a third of my rifles have fixed scopes of 2.5X to 6X. Often it’s a matter of style. A fixed 4X just looks right on certain classic rifles, such as the Ruger No. 1 in 7x57 mm Mauser. Fixed scopes also cost less, and for most big-game hunting, we really don’t give up any practical advantage when using a 4X or 6X.

There’s also something aesthetically pleasing about simplicity, especially in a world that seems to grow more complex with each sunrise. Fifty years ago, a 4X scope on your .30-’06 would have put you on the cutting edge of long-range accuracy. Today, the same scope and rifle mark you as a reactionary—either hopelessly behind the times or a hunter who insists on getting close enough to make sure. I guess this is all part of what was termed situational ethics back in the 1960s. Whatever side you prefer, don’t worry about the scope. These days, there’s one out there for you.

This feature article, "Understanding Variables," appeared originally in the November 2004 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.