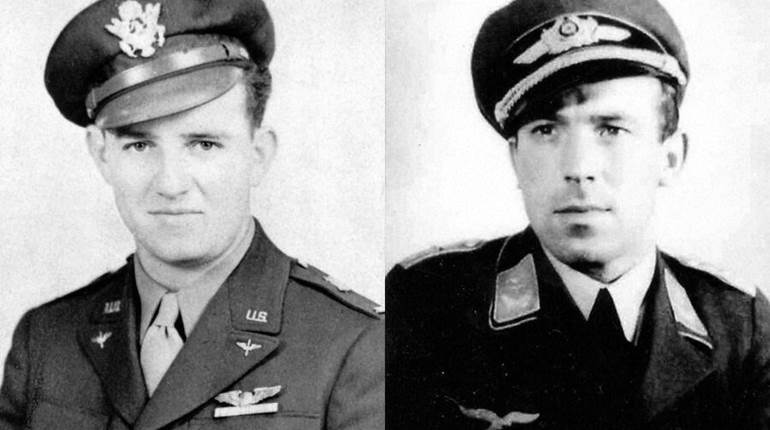

During World War II, this SOE team, led by Patrick Leigh Fermor (seated, center) abducted the German commander of Crete and exfiltrated him to Egypt. At least three UD submachine guns are visible in this photo.

The least-known American submachine gun to see combat in World War II was the United Defense M.’42. Some also regard it as the best. Today, the UD remains cloaked in obscurity because it was never formally adopted by the U.S. military. It was the only submachine gun procured by the U.S. government not for its regular armed forces but exclusively for its then-secret Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

By an extraordinarily convoluted route, the UD M.’42 became the unrecognized “standard” OSS submachine gun of World War II, widely issued to American and Allied personnel serving in special operations and “Jedburgh” units. At least 4,000 were sent to U.S. Navy installations in the Far East, thence to the Chinese. Some went to OSS Detachment 101 in Burma, and many more were distributed to resistance groups in Nazi-occupied countries. In 1944, the OSS airdropped a total of 2,405 UDs with 12,000 magazines into northern France. Still others were transferred through the Lend-Lease program to the UK and employed by its Special Operations Executive (SOE), particularly in Greece, Italy and Yugoslavia.

Despite its limited production—only 15,000 were ever produced—the UD was one of the finest representatives of first-generation submachine guns (SMGs), milled from solid steel and stocked in walnut. A blowback-operated arm firing from the open-bolt position, it had been designed just before World War II by Carl G. Swebilius, one of America’s outstanding gun designers.

“Gus” Swebilius was born in Sweden in 1879 and emigrated to the United States at the age of 17. During World War I, while employed by Marlin-Rockwell Corp. in New Haven, Conn., he had re-designed the Colt/Browning “Potato Digger” to create the Marlin Model of 1917, the first American machine gun purpose-built for aircraft. Not only a gifted inventor—he held more than 60 patents in his lifetime—he became an eminently successful industrialist. In 1926, he founded the High Standard Mfg. Co., making deep-hole drilling equipment, and earned millions from it.

In 1940, Swebilius applied for four patents on a new submachine gun, assigned to High Standard. The patents asserted—with considerable justification—a superiority to existing designs in simplicity, ruggedness and reliability under adverse conditions and ease of disassembly for transportation. A few .45 ACP toolroom prototypes were formally submitted to the U.S. Army for testing at Aberdeen Proving Ground in November 1941, a month before Pearl Harbor. The gun passed all tests, but no U.S. order was forthcoming.

In Ordnance Corps jargon, there was “no present requirement” for such a firearm. In fact, up until 1940, the hidebound U.S. Army had purchased fewer than 1,000 Thompson SMGs, mostly for the cavalry. The British army, even more abhorrent of what it viewed as “gangster weapons,” had no SMGs at all.

High Standard also tried to interest the Netherlands Purchasing Commission with a model chambered in 9 mm Luger, a cartridge more to European tastes. An early manual called it “Model UD of 1941.” The Dutch, their homeland having been occupied by the Germans, had an office in New York to buy arms to defend the East Indies against Japanese invasion. High Standard hired Frank Jonas, a well-recognized dealer in arms and aircraft, as its agent to close a deal, but the Dutch demurred because the gun had not yet been approved by any military power.

Meanwhile, fortune smiled on High Standard. In November 1941, it received a $15 million contract—with cash up front—to produce .50-cal. Browning machine guns in a program for the British government. In a Herculean achievement, Swebilius built and equipped a new factory with 1,800 workers and commenced production in only eight months. He had no excess capacity to manufacture his SMG design.

Enter the United Defense Supply Corp., a purely private firm unconnected to the U.S. government. It was organized by Arthur J. Pope and Col. Arnold Strode-Jackson, the latter a former member of the British Purchasing Commission.

United Defense had no manufacturing or engineering facilities of its own; like Jonas, it was principally a promoter and broker conversant with negotiating government contracts. For what later were termed “obvious reasons,” Pope and Strode-Jackson enlisted a New Haven socialite named Stewart Inglehart, internationally famous as a polo player. He provided the enterprise with both recognition and money.

If an order from the Dutch could somehow be landed, factory capacity was available at the Marlin Firearms Co. in New Haven. It could not have been coincidental that United Defense listed its offices at 85 Willow St.; the Marlin factory occupied nearly the entire unit block of Willow Street.

It is unknown today exactly who approached whom, but, on Dec. 12, 1941, High Standard licensed sole and exclusive rights to manufacture and sell the gun for five years to United Defense. It was estimated the gun would cost about $45 to manufacture in quantity, then roughly one-quarter the cost of an M1928 Thompson.

The license terms required an annual minimum royalty paid to High Standard, plus a 10 percent royalty on each further gun sold, but not less than $7.50. If a year passed without sales of at least 1,000 guns, High Standard could cancel the license.

Using Strode-Jackson’s contacts to obtain a semi-official British “endorsement” of the gun (an ambiguous declaration of “adaptable for military use”—not the same as “adoption” or even “approval”), UD finagled two orders from the Dutch totaling 15,000 guns in 9 mm. UD then contracted with Marlin to manufacture the gun and with Seymour Products for the magazines.

In February 1942, the U.S. Army reversed itself and abruptly discovered a dire need for submachine guns. It urgently sought an alternative to the Thompson, the production of which was too slow and hideously expensive. UD was invited to submit cost proposals for 94,000 guns at a rate of 400 per day or 150,000 guns at 1,000 per day. Delivery had to be completed by the end of 1942. UD responded by quoting $54 per gun, royalty included.

However, this proposal was stalled by legal complications. The Ordnance Dept., in the autocratic persona of Col. René Studler, considered High Standard’s royalty to be “exorbitant” and UD a mere “middle man.” Studler, who earlier had stimulated development of the M1 carbine by Winchester, wanted to deal only with the manufacturer. But neither High Standard (the owner) nor UD (the licensee) were actually the manufacturer. And Marlin—which was—had no independent right to be.

Studler held out the plum of an immediate order if UD eliminated High Standard’s royalty—quite unrealistic, considering that Swebilius had a high stake in its design and development. Moreover, Studler also demanded that UD assign to the U.S. Army all of its rights to the gun, thereafter to make it where and by whomever it pleased. This was even less realistic, and UD understandably refused.

The resulting impasse was soon overtaken by events: The Hyde-Inland M2 submachine gun was adopted as “substitute standard,” and, by July 1942, a simplified M1 Thompson entered mass production. Deliveries soon satisfied Army requirements, and the need for a Thompson replacement lost urgency. Ultimately, the emergence of the vastly cheaper stamped-metal M3 “grease gun” (also midwifed by the impatient Col. Studler) doomed any U.S. Army procurement of either the UD or the M2.

Meanwhile, production of the 9 mm version for the Dutch was beset with seemingly endless delays. UD and Marlin could not obtain a satisfactory technical package and toleranced drawings from High Standard. They intimated that High Standard was deliberately dragging its heels, perhaps looking ahead to the end of its British contract and hoping to stall long enough to retrieve the UD license. Exasperated, Marlin engineers produced their own blueprints and commenced production in early 1942. Its designation was “United Defense Model of 1942” or just “UD M.’42.”

However, before any could be delivered, Japan overran the Dutch East Indies. The hapless Dutch government—now marooned in exile—turned over its contract to the United States government, reserving only 800 guns for use in its West Indies colonies and elsewhere. Beginning in August 1942, the U.S. Munitions Assignments Board allotted all of the remaining 14,200 guns to the OSS. Marlin’s last deliveries were completed in January 1943.

Distributed from OSS depots, the UD soon gained fame and respect. Among Greek partisan groups, the UD was popular, along with the British gold sovereign, as a unit of currency. Case in point: 40 UDs were demanded in return for cooperation with an SOE mission to blow the Gorgopotamos railway bridge in 1943. On Crete, UDs were carried by an SOE team led by a young Englishman, Patrick Leigh Fermor, who kidnapped the island’s German commander, Maj. Gen. Heinrich Kreipe, and exfiltrated him to Egypt. The exploit was later dramatized in the 1957 movie “Ill Met By Moonlight” starring actor Dirk Bogarde as Leigh Fermor.

Overseas, the UD was commonly called the “Marlin,” though the origin of such usage is a minor mystery: Marlin’s name does not appear anywhere on the gun. It is marked only “United Defense Supply Corporation, New Haven, Connecticut” and “UD M.’42.” This is not a military designation; none of the Ordnance inspection stamps or property marks typically found on official U.S. arms are present.

A further anomaly is that many, if not most, UDs have two different serial numbers. One number is stamped twice, on both the underside of the receiver and on the underside of the trigger housing. These ordinarily match. However, in a more prominent location vertically on the right side of the trigger housing, a different number—varying from 1-200 higher or lower than the other serial numbers—is factory-stamped in the same distinctive font. No explanation for this oddity has been discovered.

From the soldier’s perspective, the UD proved to be an excellent firearm. Robust and reliable, it weighed only 9 lbs. empty, a pound lighter than a Thompson and much simpler to maintain. Lively in the hands and well-balanced, it pointed naturally—more like a rifle than an SMG—in this regard it put the Thompson, British Sten and German MP40 to shame. Accurate in single shots, the UD was also very controllable in full-automatic fire, despite a cyclic rate approaching 1,000 rounds per minute. U.S. infantry doctrine considered such a high rate to be excessive, but it was prized by some expert users disciplined to fire in short bursts.

Apart from its chambering, the U.S. Army still preferred .45 ACP, the UD’s shortcomings were relatively few—an inconvenient safety/selector lever and awkward magazine change—though the Thompson was equally deficient on these points. Moreover, like practically all first-generation SMGs, the UD had no positive lock to prevent accidental firing from inertial bolt bounce if dropped on its butt or carried muzzle-up while jumping into a trench or down from a truck.

Swebilius had skillfully combined in a single design some of the best features of earlier guns. It was an exhibition of the kind of genius that would later explain the success of Mikhail Kalashnikov’s AK-47.

The non-reciprocating cocking handle, for example, is borrowed from the Beretta 38A; it completely covers its operating slot in the receiver. After cocking, it is pushed back to its forward position to keep out debris. The bolt has two features lifted from the Thompson. Its reduced frontal diameter fits closely into the narrow feedway of the receiver to enhance positive feeding. Once a cartridge is stripped from the magazine, it has nowhere to go except into the chamber. Also, a hammer is mounted on the bolt; it strikes an abutment in the receiver when the bolt closes and pivots to hit the firing pin, avoiding much of the risk of premature ignition inherent in a fixed firing pin.

The magazine is almost an exact copy of the 20-round Thompson magazine but scaled down to 9 mm Luger, which may explain the common but erroneous listing of its capacity as 20 rounds. In fact, it holds 25. It is of a double-column, staggered-feed design, extremely reliable and easy to load. However, while its T-shaped spine ensures rigid mounting, it also makes rapid magazine changes easy to fumble—a fault also inherited from the Thompson. A bolt hold-open engages when the magazine is empty, but, unlike the Thompson’s, it must be manually tripped to continue firing after a fresh magazine is inserted.

A “double” magazine was also manufactured. Two magazines were spot-welded front-to-front, one upside-down, offering a total of 50 rounds carried on the gun—though its usefulness under combat conditions is doubtful, since the second magazine’s lips and ammunition were fully exposed to dirt and vegetation if the shooter is in the prone position. No protective cap, such as those issued for M1 carbine magazines, is known to exist for the UD, though a wide belt pouch designed to hold UD double magazines was produced and issued.

The selector/safety lever is located on the right side of the trigger housing—unfortunately, shooters must release their grip to reach it. The safety works only when the bolt is cocked. Peculiarly, if the safety is “on” when the bolt is retracted, it automatically flips the selector to semi-automatic—putting a premium on thorough familiarization!

The takedown is unique. Pulling down a lever on the right side instantly detaches the barreled upper receiver containing the bolt from the lower receiver, comprised of the buttstock, trigger housing and magazine holder. In its day, the UD’s recoil spring and guide-rod assembly was also a clever innovation: a simple captive unit only 6" long—no struggle to remove or replace. This was soon copied by the Russians for their PPSh-41 and in many SMGs thereafter.

A rear aperture sight, click-adjustable for both windage and elevation, is integrally contained inside the trigger housing and can be rapidly cranked up by a thumbwheel above the trigger—perhaps the neatest, most elegant rear sight ever employed on an SMG. Perversely, its elevating post is ungraduated; users apparently had to memorize the number of “clicks” to zero at a given range.

Presumably for concealment in resistance use, at least one UD was experimentally modified with a rear pistol grip in lieu of the buttstock; its barrel appears to be easily removable by unscrewing a knurled barrel nut. Of this version, only a photograph survives. In early 1943, hoping to attract further sales, UD presented another submachine gun to the OSS for testing; it offered the option of readily changing cartridges from 9 mm Luger to .45 ACP by switching the barrel, bolt and magazine. Though called the UD M.’43, in fact, this was a totally different gun designed and patented by Arthur J. Pope. The test proved unfavorable, and no order materialized.

In 1948, Marlin acquired from High Standard exclusive rights to manufacture and market the UD to foreign governments, but the war had left the world awash in cheap surplus arms, and there were no takers.

The last known combat use of the UD was in Korea, unfortunately against American soldiers. Many UDs turned up in the hands of Chinese communist troops sent across the Yalu River in 1950. Gus Swebilius would not live to see the irony of Lend-Lease to China; he died in 1948, at age 69.

Practically all UDs encountered in the United States today are from a lot of several hundred purchased from the Dutch government in 1953 by Western Arms Corp. in Los Angeles, Calif. They were brought into the Port of New York Free Trade Zone (FTZ) and were sold from the FTZ over a period of four years. Known serial numbers are in the mid-11,000 range and in the mid-14,000 range. More than 200 were purchased by Interarmco (later Interarms), then based in Washington, D.C. Most, except for a handful sold to police departments, were welded to be unserviceable, facilitating easy sale by Navy Arms, Golden State Arms, Hy Hunter and other resellers without payment of the $200 transfer tax imposed on NFA firearms. In those days, the tax was confiscatory, considering that the gun was widely advertised for $39.95. About the same number of UDs were made as original Colt Thompsons (15,000 each), but the UD’s survival rate was far lower. As a consequence, the UD is a rarer gun today than the Colt.

The highest serial number observed is 15,103, which resides in the Springfield NHS collection with two of the original .45-cal. U.S. test guns, Serial Nos. 6 and 7. The Smithsonian Institution holds Serial No. 2, reportedly donated in 1981 by the Pope family.

World War II demonstrated that quality materials and fine workmanship were an unsustainable burden in wartime. Though simpler than the Thompson, the UD—milled almost entirely from forgings and bar stock—was still too slow and expensive to produce. Only a few minor parts, such as the sling swivel plates, were stampings, and its elaborate rear sight was a gross extravagance. The beautifully crafted UD was consequently among the very last traditional steel-and-walnut submachine guns to appear in service.