They tell me that a picture is worth 1,000 words. When it comes to the Winchester Model 1897 “Trench Gun” in World War I, a combat photo of the gun is worth all the words I could ever write about it.

What all the fuss is about: The 12-ga. Model 1897 Winchester, adopted as the U.S. “Model of 1917 Trench Shotgun.” One of the most intimidating looking firearms ever made!

During 2010, I was working on a photo-study book of the firearms used by the American Expeditionary Force during World War I. Pre-production work was coming along well, and when I had a few questions about some of the finer points of the small arms of the American Expeditionary Force, I turned to my friend Bruce Canfield. Bruce, an American Rifleman Field Editor, easily answered my questions, and then he had one of his own.

“How many photos do you have of ‘trench guns’ in the hands of Doughboys?”

I didn’t have any at that point, but I wasn’t worried. I had been lauded for my ability to find images of even the most obscure guns. How hard could it be to find photos of World War I trench guns in combat? Bruce noted that he had looked for them unsuccessfully for more than 30 years. I confess to having a bit of an arrogant attitude about it, and so I dove into the research.

Fast forward to the final production of my book. I had but one photo of a trench gun, and it wasn’t in the hands of anyone, let alone a Doughboy in a combat zone. In the years since, I’ve found a couple more images of trench guns in World War I, but not one in the hands of a Doughboy.

So, why are there no photos of a Model 1897 or the “Model of 1917 Trench Shotgun” (its military designation) in action during World War I?

I can tell you that the U.S. Army Signal Corps images from World War I represent a fantastic collection. I’ve been through all of it, but there are no photos of trench guns in combat. None. It seems rather strange, given that the combat shotguns were important arms in the American arsenal. The paper documents about development, production, allocation and the combat use of the shotguns all exist. But if you went by the available official images, you would have to conclude that only a handful of them ever made it to the front.

Trench Gun recreational shooting: Men of the fledgling U.S. Army Air Service break some clay pigeons with the Model 1897 trench gun at Issoudon, France, during June 1918.

This little bit of military photo and firearms trivia is wrapped up inside a much larger issue, with implications that reach all the way up the chain of command in the AEF.

American troops began to arrive in France in late 1917. They brought with them an interesting mix of small arms. Some of them, like the M1911 pistol and the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle were greatly advanced for their time. Others, in particular the Model 1897 Shotgun, adapted to accept a bayonet, were uniquely American. While Europeans considered a shotgun to be nothing more than a bird-hunting arm, the American military was familiar with the man-stopping power of 00 buckshot from the recent campaigns in the Philippines and Mexico. American leaders reckoned that the firepower of the pump-action shotgun could provide a war-winning advantage in the stalemate of trench warfare.

The Trench Gun in a combat zone: This image is a one of a series of comparative photos taken by a U.S. Ordnance team during the last week of World War I. This is the only one that made it past the censors.

German military planners heard the ominous sound of the doomsday clock ticking as soon as America entered the war in April 1917. Germany feared the arrival of U.S. troops, and the Kaiser’s hopes for victory rested on a massive breakthrough before American manpower and industrial might could be brought to bear. The Ludendorff Spring Offensive of 1918 put German troops into mortal combat with significant numbers of American Doughboys for the first time. American firepower and fighting spirit helped stop the Germans cold.

Beginning in July 1918, the Germans captured a few Americans armed with trench shotguns, and, after a time, this became the subject of a bizarre controversy.

On Sept. 19, 1918, the U.S. Secretary of State received the following protest by cablegram from the government of Germany:

“The German Government protests against the use of shotguns by the American Army and calls attention to the fact that according to the law of war, every U.S. prisoner of war found to have in his possession such guns or ammunition belonging thereto forfeits his life. This protest is based upon article 23(e) of the Hague convention respecting the laws and customs of war on land. Reply by cable is required before October 1, 1918.”

Clearly, the trench guns had gotten the Germans attention. The Acting Judge Advocate General of the U.S. Army, Brig. Gen. Samuel T. Ansell, addressed the ridiculous German protest with a memorandum on Sept. 26, 1918. Within his statement, he completely debunked the German protest in both legal and ballistic terms, and concluded that the German gripes were “without legal merit.” The U.S. government also responded, in no uncertain terms, to the German threat to execute Americans captured with a shotgun or buckshot ammunition:

“The Government of the United States notes the threat of the German Government to execute every prisoner of war found to have in his possession shotguns or shotgun ammunition. Inasmuch as the weapon is lawful and may be rightfully used, its use will not be abandoned by the American Army.

“If the German Government should carry out its threat in a single instance, it will be the right and duty of the United States to make such reprisals as will best protect the American forces, and notice is hereby given of the intention of the United States to make such reprisals.”

Uncle Sam doesn’t take kindly to threats, and the Germans were well advised not to harm those few Americans they managed to take as prisoners. However, the German protest presented some major issues for Gen. Pershing and the troops of the AEF, as the Kaiser’s propaganda machine cranked up the volume. American troops were described as “undisciplined and barbaric,” and “incapable of using proper rifles.” It might have been chalked up to sour grapes and name-calling, but there were some other potentially serious consequences for American troops stemming from the German shotgun protest.

At that time, America was still considered a junior partner among the Allies. British and French commanders were hoping to use American troops as cannon-fodder for the autumn offensive against the Hindenburg Line. General Pershing was adamant in his desire that American troops would remain under American command. A public relations problem like the trouble over trench guns might have given French and British leaders enough leverage to usurp control of American troops. It seems apparent that Gen. Pershing wasn’t taking any chances.

I put two and two together and came up with a researcher’s opinion on why no official photographs can be found of Doughboys carrying trench guns in the World War I. I believe that AEF command ordered that photos of trench guns in combat be censored, and ultimately eliminated. This effort would make certain that the press could not accidentally print any “embarrassing” images of the Doughboys equipped with shotguns. The trench guns would remain in France and continue to do their deadly, effective work, but there would simply be no photographs allowed to document it.

Certainly, the Signal Corps files have been carefully cleansed of trench gun images. Stampings on official images from World War I show the photos were marked and approved in France first, and then again in Washington, D.C. Apparently, careful attention was paid to the photographic content.

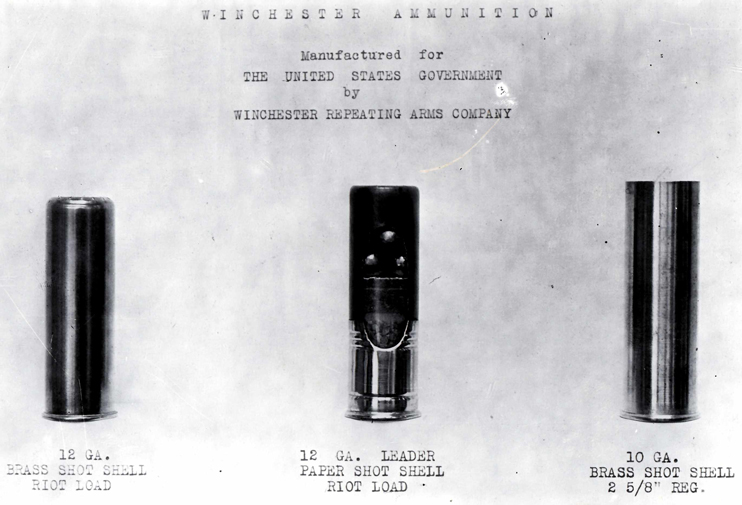

The biggest complaint about the Trench Gun was its paper ammunition. Rain, mud, and exposure to damp conditions could cause the paper shells to swell and render them useless. Brass-cased shotgun shells were made, but few were issued. Federal bean-counters cried bloody murder over the cost. This same issue dogged U.S. Marine Corps use of the combat shotguns during World War II.

There is also some anecdotal evidence of shotgun censorship: after my book “The Yanks Are Coming” was published, I had a conversation with Bob Landies (the founder of Ohio Ordnance Works) about the topic. He remembered his boyhood conversations with an old Army Ordnance sergeant, a man who had served in France during World War I. Bob met him as a youngster in the 1960s and recalled that the former Doughboy stated: “We were ordered that there were to be no pictures taken of trench guns.” It certainly makes sense to me.

I would love to know if those orders were ever issued in print form. Until I have that specific proof, my theory will be nothing more than an opinion, unsubstantiated by certain critical facts. Regardless, there are no known photos of Doughboys in the trenches, or in the fields, or in the Argonne forest with a Model 1897 trench gun. There is a possibility that there are photos taken by the Doughboys themselves show a trench gun in combat, but I have never seen one. I’ve heard many rumors, but investigation of those private images have always come up empty.

Maybe one of our intrepid readers will come forward and present us with a genuine World War I “trench-gun-in-a-combat-zone” photo. It would be an incredibly rare sight to see. And a uniquely American one at that.