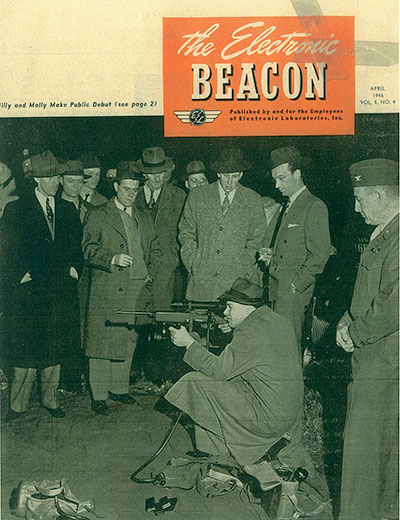

Sergeant Stanley G. Tiemann of the U.S. Army’s 546th Engineer Detachment at Ft. Lewis, Wash., is shown here sighting a T3 carbine with an M2 infrared vision scope.

For countless centuries, fighting men have used the cloak of darkness for concealment from their adversaries. Various methods were devised to counter this advantage, including torches, flares, rockets and, later, searchlights, but these proved to be ineffective for a variety of reasons. World War I resulted in renewed interest in the development of night-vision technology, but no notable advances were forthcoming by the time of the Armistice.

Early in World War II, the Germans developed some rather rudimentary night-vision devices, but, due to the size and weight of the equipment, their use was initially restricted primarily to tanks and other vehicles. The Soviet Union also experimented with night vision circa 1942, but little progress was made by the time the war ended.

When the United States entered World War II and our troops were deployed to the Pacific Theater, it became painfully apparent that the Japanese were masters in nighttime infiltration tactics. It was equally apparent that effective night-vision devices would be extremely helpful in combating this very real threat.

To that end, in 1943, the U.S. Army Engineer Board at Fort Belvoir, Va., began development of an infrared sight to provide night-vision capability to our troops. The Army engineers devised a rather rudimentary instrument consisting of an electronic telescope and sealed-beam light, somewhat similar to an automobile headlight, fitted with an infrared filter. A lead-acid battery to power the device was carried in a canvas knapsack. An improved version of the infrared sight was designated as the T120.

The Army eventually decided that an M1 carbine with a suitable mount to accommodate the sight would be a satisfactory platform for such use. Since night shooting would typically be at relatively close range, the .30 Carbine cartridge was believed to be adequate. Also, the infrared scope added rather significant weight and bulk, and a carbine fitted with the relatively cumbersome infrared sight would be easier to handle than a heavier rifle, such as the M1 Garand.

In June 1943, the Army Ground Forces Headquarters had developed a carbine fitted with a telescopic sight to determine the feasibility of a lightweight sniper rifle. The Inland Mfg. Division of General Motors fabricated a carbine with integral scope mount brazed onto the receiver and fitted with a Weaver M73B1 telescope as used with the Remington M1903A4 sniper rifle.

The prototype “sniper carbine” was designated the M1E7. Extensive testing was conducted at Aberdeen Proving Ground from early November 1943 to January 1944. The results were not impressive, and the M1E7 telescopic-sighted carbine was not recommended for further service testing or adoption. However, it was recognized that the basic design of the modified “sniper carbine” would be ideal for use with the infrared sight.

Inland was selected to develop a carbine based on the experimental M1E7, with an integral receiver mount to accommodate the infrared sight. The modified carbine fitted with the T120 scope and infrared lamp was tested by the Ordnance Dept. Engineering Board and recommended for limited procurement on Feb. 17, 1944, as the “Carbine, Caliber .30, T3, Sniperscope.” The recommendation was approved on March 16, 1944.

The first production contract for 1,700 T3 carbines was granted to Inland, but the company manufactured only 811 before the contract was terminated due to the war ending. Likewise, Winchester Repeating Arms Co. subsequently received production contracts for 5,160 T3 carbines but turned out only 1,108 by the time the contracts were cancelled soon after V-J Day.

The Inland and Winchester T3 carbines were very similar except for some configurational differences in the integral sight bases and, of course, the manufacturer markings. The right side of the rear sight base was marked “US CARBINE/CAL .30 T3.” The Inland and Winchester T3 carbines were serially numbered in special blocks separate from the standard M1 and M2 carbines made by the two contractors.

The original T120 infrared scope, later designated as the “Sniperscope M1,” was followed by an improved version, the “Sniperscope M2.” However, the latter version saw little, if any, combat use in World War II. In addition to the infrared sights mounted on the T3 carbines, there was a hand-held version, dubbed the “Snooperscope,” that was intended for observational purposes. The Sniperscope and Snooperscope instruments were dubbed “Milly” and “Molly.”

The only significant difference between the T3 carbines and the standard M1 carbine was the integral scope mounts on the receiver and the configuration of the stock. All T3 carbines were semi-automatic and did not have selective-fire capability. A cone-shaped flash hider, first designated as the “T23,” was approved for standardization as the “Hider Flash, M3” on March 9, 1945, but none were put into production before the end of the war. After the war, the M3 flash hiders were manufactured by Springfield Armory and the Underwood Co., and these saw a substantial amount of use with the later post-war infrared-capable carbines.

William W. Garstang, one of the individuals involved in the development of T120 infrared scope, related in an article he penned for the April 1946 issue of The Electronic Beacon that the Electronics Laboratory produced 1,700 infrared scopes in World War II and built a total of 4,500 before the company was sold to another firm in 1947. It is reported that all 1,700 of the wartime infrared scopes were slated to be sent to either Okinawa or the Philippines.

Garstang reported “[U]ntil mid-1946, the performance of the Sniperscope and Snooperscope, known to the GIs as Milly and Molly, was little known. However, they were used in the invasion of Okinawa, on Luzon and in the final cleanup of the Philippines. They effectively stopped all (night) infiltration and eliminated one of the worst features of the Pacific warfare … .”

Nighttime infiltration by the Japanese had been a cause of much concern for American troops throughout the war, and the infrared-sight-equipped T3 carbine was tailor-made to counter such tactics. Sniper historian and author Peter Senich elaborated on the successful combat use of the infrared sights in World War II: “A night-vision capacity was to prove particularly effective in combating Japanese infiltration tactics conducted during periods of darkness in the Pacific. It was reported during the first seven days of action of the Okinawa Campaign that the Sniperscope (infrared) accounted for approximately 30 percent of the total Japanese casualties inflicted by small arms fire.

Combat reports cite approaching groups of Japanese being thoroughly decimated while attempting to pick their way through American lines. From that point forward, night activity of the Imperial Japanese solider was to be infinitely more hazardous. Although several thousand infrared units were manufactured during World War II, only about 200 were actually employed in the South Pacific. The Japanese military, cognizant of the infrared principles and techniques, was, in fact, developing units for small-arms use late in the war. However, operational devices were not known to be employed in actual combat.”

Combat use of the infrared-sighted T3 carbine and its effectiveness during the Okinawa campaign was also discussed in Robert Rush’s book GI: The U.S. Infantryman In World War II, “There was a lot of talk about a new weapon some of the members of the Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon were carrying. It looked to many like one of Buck Rogers’ ray guns, with a large dish mounted beneath a … carbine and a large flashlight on top with a power cable leading to a metal box carried in a backpack. They called it a ‘sniperscope’ for good reason, and the Army had developed it for the sole purpose of thwarting Japanese infiltration.

Using this weapon, a soldier could see in the dark to a range of about 70 yds. (64 m), with objects appearing in the scope in various shades of green. About 30 percent of the total Japanese casualties inflicted through rifle fire during the first weeks of the Okinawa operation were from the sniperscope … . Although they were heavy and bulky, it was nice to sit in a concealed position and watch the green images of Japanese soldiers creep forward. A quick blast … and another enemy soldier lay dead. After a few nights, they discovered rain and night illumination tended to cut down the scope’s efficiency.”

Apparently, none of the T3 carbines and their infrared scopes were deployed to the European Theater prior to the end of the war. Even though more than 1,900 T3 carbines and some 1,700 infrared sights were made during the war, only about 200 made it overseas and saw active combat use for a few months in the later Pacific campaigns. Nevertheless, they inflicted many more enemy casualties than would be expected given the numbers employed.

The infrared-capable T3 carbines were undoubtedly a revelation to the American troops who had, rightly, feared Japanese night infiltration tactics since the early Guadalcanal campaign. It is unfortunate the infrared sights weren’t available in 1942, but advances in technology cannot always be rushed.

The Germans, too, developed a number of infrared night-vision instruments for vehicle, aircraft and fire-control applications. Well before the end of the war, the Germans started development of an infrared night-vision sight for their Maschinenpistole 43 (MP43) assault rifle, which was given the marvelous nickname Vampir (vampire). The Wehrmacht had anticipated the use of infrared night-vision small arms sights by the Allies and produced about 10,000 hand-held devices that could detect infrared light sources. However, combat use of infrared night-vision sights for firearms by the Germans was virtually nil and did not create any significant problems for the Allied forces.

Following the conclusion of World War II, the U.S. military continued development of improved infrared night-vision sights. Very few genuine T3 carbines have survived, as virtually all were destroyed (“demillled”) by torch-cutting after being withdrawn from service after the war. In lieu of the specially made T3 carbine, a separate mounting bar for the infrared sights that could be attached to standard M1 or M2 carbines was developed. The mounting bar was installed by attaching the rear portion into the carbine’s dovetail sight base (after removing the rear sight) and clamping the front to the barrel.

The only modification required to the standard carbine was an oval hole milled into the handguard to accommodate the front barrel clamp. The light source was mounted on top of the scope as field reports from World War II indicated that the infrared lamp mounted on the bottom of the stock could sometimes be obscured by foliage. After the war, the M1 and M2 infrared sights still in inventory were modified to relocate the light source above the scope.

The M2 carbine retrofitted with the modified M1 or M2 infrared night-vision sights with the attached separate mounting bar was standardized as the “Carbine, Caliber .30, M3.” This change in nomenclature has resulted in some misunderstanding as the World War II T3 carbine is sometimes confused with the post-war M3 carbine. The two are differentiated by the fact the T3 had a special receiver with integral mounts and was semi-automatic only, while the M3 was a M2 carbine (either a purpose-made M2 or a M1 converted by means of a T18-type kit) with the mounting bar added and equipped with an infrared night-vision sight.

In the very early 1950s, an improved infrared night-vision sight, the “M3,” was adopted and officially designated “U.S. Sniperscope, Infrared, Set. No. 1, 20,000 volts.” The M3 infrared scope was used with the M3 carbine and saw service during the Korean War. It remained in limited use into the early Vietnam period. The M3 infrared sights are still around today in fair numbers, although many are inoperable due to the understandable deterioration of their almost 70-year-old electrical components.

Technological improvements eventually resulted in greatly improved infrared night vision devices that could be used on the M1 and M14 rifles. Later “passive” night-vision devices using highly amplified ambient light, such as moonlight and even star light, for night vision capability were developed and saw use primarily with the M14 and M16 rifles. Today, the U.S. military makes extensive use of a host of modern night vision devices and their utilization is generally taken for granted.

Night-vision technology has come a long way since 1945. However, the lineage of U.S. military night-vision-equipped arms can be traced directly back to the T3 carbine and its infrared sight fielded in the closing months of the Pacific War. While today’s high-tech night-vision devices are vastly superior to the now-antique infrared sights used in the latter stages of World War II, Milly and Molly were welcomed with open arms by the American fighting men who heretofore had been at the mercy of the darkness when battling their stealthy Japanese adversaries.