In July, a group of writers, firearm manufacturers and private students met at Gunsite Academy (gunsite.com) near Paulden, Ariz., to explore the current state of the Scout rifle. It had been 33 years since Col. Jeff Cooper, who founded the facility, convened the first such conference with the goal of proving out the concept of a “general purpose” rifle platform. As a Marine officer and a keen student of military history, Cooper was familiar with the term “scout” as it applied to the lone combatant striving to gather intelligence while avoiding contact. His appropriation of it was intended to connote an all-around rifle, typically a bolt-action in .30 caliber, intended primarily for hunting game and pressed into defensive service only in a pinch. Nowadays, such a concept seems to evoke either enthusiasm, skepticism or downright derision.

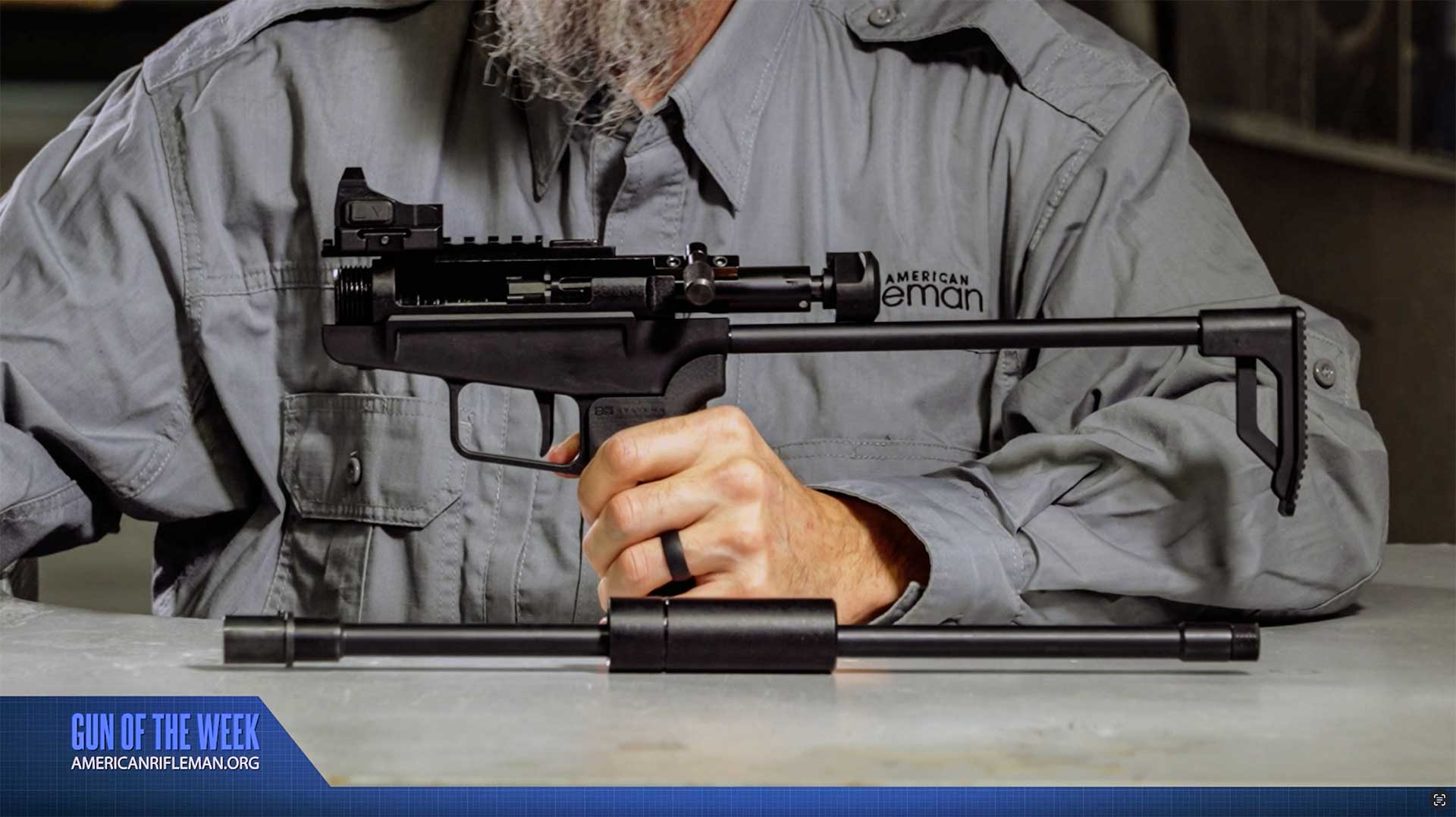

Regardless, contemporary riflemen are at least familiar with it since several mainstream manufacturers have answered market demand with their own unique iterations of the Scout. Among those represented at the event were the Cooper-sanctioned Steyr, with its integral bipod and magazine storage; the Gunsite-endorsed Ruger, with its length-of-pull adjustment and flash hider; the Savage, with its adjustable cheekpiece and AccuTrigger; and the Mossberg MVP, (pictured above) with its multi-magazine compatibility and lengthy Picatinny rail. I wrung out the latter, the source of my invitation to the event, and the accuracy and reliability of its proven MVP bolt-action made easy work of connecting quickly and repeatedly with my targets.

Under the watchful eye and with expert guidance from Gunsite instructors Il Ling New, Mario Marchman and Gary Smith, our group happily endured three days of training with the rifles under the high desert’s oppressive 108° F heat. We shot at paper targets from 25 to 200 yds. and from standing, kneeling, sitting and prone and then, on the fourth day, casually competed against each other and the clock by shooting steel targets at unknown ranges. While each of the platforms represented there, including a couple of custom guns, exhibited both positive and negative idiosyncrasies, all were entirely serviceable and practical—with capabilities far ahead of the one-off prototypes from Cooper’s era that were on display at the conference.

On day five, as we gathered to review the results, critique the platforms, and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the Scout concept, there was more consensus than dissent, even among competing manufacturers. It seems Cooper’s idea had not only stood the test of time, it had successfully navigated the sea of modern sporting rifles, adopting from them characteristics that only enhance its relevance. It was further proof that Cooper’s work with firearms was as fundamentally sound as were his advancements in training—the latter evidenced by Gunsite’s celebration of 40 years in operation this year.

If the Scout rifle concept has a fundamental flaw, it likely belongs less to its founder and more to followers who often interpret it as rigid dogma rather than flexible doctrine. I saw evidence to support Cooper’s own willingness to consider other rifle platforms while visiting his nearby home where his widow, Janelle, and daughter, Lindy, graciously entertained our group with refreshments. There, in his gun room, were examples of rifles—an early Ruger Mini-14, a Marlin lever-action and a Garand-based Beretta BM59—that, while not turnbolts, were nonetheless compact, fast-handling and versatile. Their prime disqualifier at that time may simply have been that there were no corresponding forward optic mounts.

With today’s raft of suitable self-loaders, straight-pulls and lever-guns, and design-specific optic mounts, Scout purists owe it to themselves to experiment even more as a way to propel the concept forward into the modern era. While the simplicity, light weight and ease of field maintenance of the bolt-action rifle for which “Scout” has become synonymous are difficult to match, the best choice for a new “general-purpose” rifle may ultimately prove to be a self-loader like those that in recent years have become so universally accepted.

My sense is that Cooper didn’t espouse the Scout rifle concept merely to elicit responses, create dogma and raise up a following—not that all those things didn’t result anyway. He simply wanted to advance “the art of the rifle,” the title of one of his several books, sharing his experiences in such a way that all could eventually reap the benefits.