The following is excerpted from "The Ruger 10/22 Complete Owner's and Assembly Guide," by Walt Kuleck. Part of Scott A. Duff Publications' Guide Series, this soft-cover book features 177 pages and 395 photographs that go far beyond the factory Ruger 10/22 manual in both scope and depth. To get your own guide, visit scott-duff.com.

Everything that Ruger learned about cost-effective manufacturing of quality products came together in the 10/22. For example, the complexity of the .44 Magnum Carbine combined with its machined-from-billet receiver must have influenced a resolution to do the next rifle more simply and less expensively, using investment casting instead of from billet. Not to mention, of course, that the .44’s aesthetics were to strongly influence the 10/22’s appearance.

The 10/22 was initially positioned as a “same-sized companion,” an understudy to the .44 Magnum Carbine. Long before the demise of the .44 in 1985, the 10/22 emerged as a phenomenon all its own.

The Genesis of the Ruger 10/22

The magic of the 10/22 stems from three creative innovations: the barrel block, the rotary magazine and the anti-bounce bolt. Let’s explore these three in the order of their patent numbers; it’s as good a way as any. First up, the barrel block.

Patent 3183167: The Barrel Block

Today’s 10/22 owner can be forgiven if she or he assumes that the barrel block mounting of the 10/22’s barrel was arranged so as to make barrel swapping easy. Well, that it does, but the reason is not ease of barrel removal; the reason is ease of barrel installation.

Consider that Bill Ruger and Sturm, Ruger have always been about innovative production technology. One has to believe that their experience with the .44 Magnum Carbine reinforced the desirability of an investment-cast receiver. The relatively lower energies of the .22 LR cartridge compared to the .44 Magnum meant that the .22’s receiver could be cast from aluminum. Lower production cost, lower weight, what could possibly go wrong?

What went wrong was the point where the barrel met the receiver. In a conventional production flow, the barrel and receiver are mated; then, the final metal finish is applied or processed. Alas, when you have a steel barrel and an aluminum receiver, you (at least in the ‘60s) had to apply two different finishes to the barreled receiver: bluing for the steel barrel, and hard-coat anodizing for the receiver. Thus, you have to finish the barrel and receiver separately before joining them.

So, “What’s the problem,” you say? Just this: to screw a barrel into a receiver using the conventional method, you must hold both the barrel and receiver quite firmly during the screwing-in. The possibilities for marring one or the other or both are legion. Thus, a method of attaching the two together that minimized the danger to the parts’ cosmetics was needed.

Bill Ruger came up with just what was required to assemble the finished barrel into the finished receiver: a dovetail arrangement with a barrel clamping block. As the method was explored and perfected, the original thought of providing an interference fit between the barrel tenon and the receiver proved to be impractical (there’s that holding-on firmly thing again) and unnecessary.

The final result was a barrel attachment that speeded production, lowering cost and thus allowing a profit at the price Bill wanted to charge. Today, for us, Bill’s innovation made it both possible and practical for the end user to quickly and easily to swap barrels in-and-out. This feature alone, in today’s “I want it the way I want it!” culture makes the 10/22 the only game in town.

Patent 3239959: The Rotary Magazine

The story really begins in 1939. While Bill Ruger was a student at The University of North Carolina, he developed an semi-auto version of the Savage Model 99. Why is this part of the story? Because the central operating feature of the 10/22 is its unique detachable rotary box magazine. If Bill Ruger weren’t already sold on the virtues of the rotary magazine, particularly for rimmed cartridges, his experience with his semiauto Savage must certainly have made a lasting impression.

While Arthur William Savage certainly created an elegant rotary magazine design, he wasn’t the first to design what was called in the 19th Century a “drum” magazine. For example, Otto Schoenauer’s 1886 US Patent number 336,443, patented in Europe two years earlier, shows a rotary magazine surprisingly similar to that of Savage’s.

Why is the rotary magazine so important to the function and ultimately the success of the 10/22 rifle? There are several reasons. The magazine of any semiautomatic (or full-automatic, for that matter) firearm is a critical part of the mechanism. Box magazines don’t require the cartridge to make a one-hundred-and-eighty-degree change in direction en route as do under-barrel tube magazines.

The cartridge in a tube magazine has to travel backwards down the tube until it’s “on-deck.” Then it has to be moved upward to be engaged by the bolt and chambered in the breech of the barrel. This typically requires some kind of lifter, which adds to the complexity of the rifle mechanism. When one keeps in mind that complexity is the sworn enemy of reliability, the simplicity of the box magazine is appealing, Further, the box magazine is typically detachable, which makes reloading with preloaded magazines quick and easy.

However, the typical detachable box magazine has two potential shortcomings. First, each cartridge, particularly in a single-stack magazine, is presented at a different angle to the breech face. That is, in a fully loaded magazine, the first and last cartridges are presented at different angles, with the intermediate cartridges presented at intermediate angles between the extreme of the first and the last. The consequence is that the feed portion of the bolt and barrel must be tolerant of these different angles of presentation, or jams are a very real possibility.

Second, the use of rimmed cartridges, such as the .22 Long Rifle, exposes the stored cartridges to the dangers of interlocking rims. If the rim of a cartridge finds itself, for whatever reason, behind the rim of the cartridge under it, the result will be a jam as both cartridges try to be fed simultaneously. Those familiar with the Mosin-Nagant “Three Line” rifle of 1891 will cite Sergei Ivanovich Mosin’s contribution to the design: a “cartridge interrupter” that inhibits rims of the rifle’s 7.62x54R rounds from interlocking and prevents double-feeding.

The rotary magazine avoids these difficulties. Each cartridge is independent of the others, and is fed at an invariant angle such that the presentation of each cartridge in turn is the same. Note Figure 7 in the accompanying patent excerpt. This figure is a “rectilinear development of the peripheral portion of the magazine rotor and cartridges,” showing how each cartridge is at the same angle as its companions. The cartridges are isolated one from the other, preventing rim interlocking and double feeding.

Patent 3240121: The Breechblock Decelerator

The third innovation that has contributed to the 10/22’s success is its “breechblock decelerator,” again from Ruger’s Harry Sefried. One of the challenges faced by the designers of semiauto (and full-auto) firearms is that of balancing bolt cycle speed and magazine cycle speed, thus ensuring that there is sufficient time for the magazine to present each cartridge in front of the bolt in time for the bolt to “pick up” the cartridge.

Harry Sefried pulled another rabbit out of his hat with this idea. He devised a means for “arresting the rearward motion of the breechblock” without adding any additional parts. By simply giving the bolt a bit of cam action, he created a semiautomatic .22 LR rifle which, as tested by Guns & Ammo in 1964, exhibited the second slowest cyclic rate of the thirteen rifles tested, at 945 rounds per minute (rpm). The slowest was the Stevens 87J, at 860 rpm, followed by the Ruger at 945 rpm.

The two fastest were the Remington Nylon 66 at 1560 rpm and the Mossberg 351C at an astounding 1600 rpm. Harry was certainly successful keeping the 10/22’s cyclic rate reined in, contributing to the reliability and durability of the little rifle. Thanks to Bill Ruger’s vision and the contributions of the engineers that he recruited, including Harry Sefried and Doug McClenahan (who later founded Charter Arms), the 10/22’s performance started off strong at its introduction in 1964, and has remained strong for more that a half-century without any design changes.

The 10/22 Takes Shape

As Bill Ruger began the design of what was to be the .44 Magnum Carbine, and later the .44's follow-on, the 10/22, it appears that he may have taken more than aesthetic inspiration from the Carbine, Caliber .30, M1 of WWII.

For example, just like the M1 Carbine, the .44 Magnum Carbine’s barreled receiver is held at the front of the stock by a barrel band, and at the rear of the receiver by hooking into a recoil block. Dismounting is accomplished by loosening and removing the band, then lifting the barreled receiver by the barrel and unhooking the rear of the receiver from the recoil block.

When the Winchester team under Edwin Pugsley originally designed the M1 Carbine, they took its trigger group from the Winchester Model 1905 autoloading rifle. The M1’s trigger group is held to the receiver by a transverse pin; the Ruger .44’s trigger assembly uses the same concept lockworks and a similar transverse pinning to the receiver.

Because of the minimal recoil of the .22 rimfire cartridge Bill Ruger and his team could dispense with the recoil block of the .44 (and the M1 Carbine). The attachment of the receiver to the stock could be done with a simple vertical screw, as described in the patent that included the innovative barrel mounting concept. However, the 10/22’s trigger assembly, which evolved from the .44’s, continued the internal lockworks design of the Winchester ‘05, albeit with two transverse pins retaining the trigger assembly to the receiver rather than the single pin of the M1 and .44.

The 10/22 retained the sleek outline of the .44 Magnum Carbine. As described earlier, the stock of the .22 was externally identical to that of the .44. The curved butt plate added to the M1 Carbine profile gave both Ruger Carbines a Western flair, creating an aura that appealed both to the M1 Carbine enthusiast and the Wild West nostalgia seeker. The 10/22 looked good, felt good, and worked well.

The 10/22 did not suddenly appear fully formed, of course. For example, the magazine design was developed using metal prototypes to determine the optimum dimensions and angles. Only then was the final form of the magazine established and molds made for the magazine’s components. Prototype 10/22 Serial Number X1 is retained in the Ruger Archives. X1 exhibits some characteristics that differ from the production version.

For one, the front sight is that of the .44 Magnum, complete with ivory insert; the production 10/22 has a brass bead. The clearance for the bolt handle in the ejection port extends further rearward along the bottom of the port in X1 versus the production gun. Underneath, the take-down screw is found in a recess that is an extension of the magazine well in the stock. What’s perhaps more interesting is that prototype X1 does not have a bolt lock. Up top, X1’s receiver does not have any provision for scope mounting. Yet, unless you look closely, X1 could very well pass as an everyday 10/22.

The 10/22 is Born

When the 10/22 rifle was released to the public in 1964, Bill Ruger made every effort to ensure that the shooting public became aware of his new product. Along with full-page magazine ads, a review in The American Rifleman had much the same effect as General Julian Hatcher’s 1949 review of the Standard Model pistol in that same influential publication.

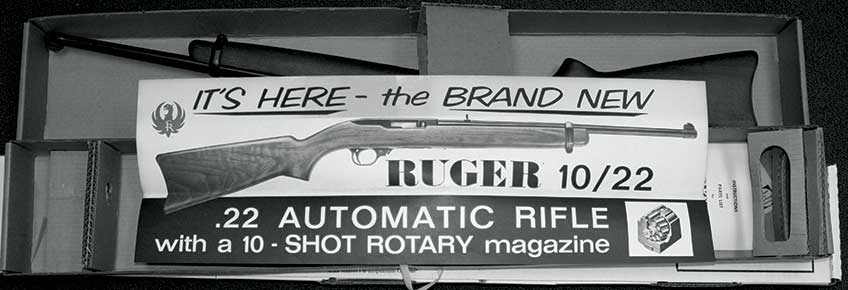

Ruger’s archives include 10/22 Serial Numbers 1, 2 and 3; S/N 2’s box still has the store banner that was included with the first rifles shipped. A particularly fine piece of walnut was used to stock S/N 1, as can be seen in the color picture on the back cover of this book. Why the name “10/22”? Presumably for “10-round .22 LR Caliber.”

The 10/22 was positioned by Ruger as “a worthy companion to the .44 Magnum Carbine,” and the two Carbines characterized as “ideal hunting companions...identical in size, balance and style, and nearly the same in weight.” Soon, the popularity of the 10/22 led Ruger to create two variations to complement similar variations of the .44 Magnum Carbine: the Sporter and the International. The Sporter had a finger-groove stock in walnut; a hand-checkered version for ten dollars extra followed. The International had a full-length stock in the fashion of the full-stock Mannlicher-Schoenauer carbines; it too had a checkered variation for ten dollars more than a standard model.

Over time the so-called fingergroove stock was replaced by the Sporter stock that we see today. The International has come and gone and come back again. Circa 1986 the first laminated stocks were offered, then composite stocks in both carbine and sporter form, and hyper-modern target stocks...actually, the story of 10/22 stocks would take up a book the size of this one were the story to be fully told.

The 10/22 Today

Today the 10/22 is available in many different forms to meet the differing needs (and wants) of a wide range of shooters. There is the original carbine, with many variations on the carbine theme: threaded barrels, hardwood, laminate, and composite stocks.

There are “tactical” versions, with fancy “tacticool” stocks. The 10/22T has been made for all these years, and has a tactical heavy barrel variation. But, the 10/22’s offerings are not limited to those in the Ruger factory catalog. Oh, no.

The Distributors Step in and Step up

The popularity of the 10/22 has inspired Ruger’s customers to offer limited, exclusive editions. Ruger’s customers? Aren’t we Ruger’s customers? Well, eventually. Ruger’s customers are the firearms distributors that actually order and pay for the products that the distributors then sell to dealers, who in turn sell to you and me. If you are a distributor and are willing to purchase a certain quantity, Ruger will cheerfully produce a special just for you.

Originally, distributor specials were simple variations on existing products. Probably the very first was the Canadian Centennial, a version of the Sporter with a commemorative medallion inlaid in the stock and a special rollmark on the receiver. Typical distributor specials were generally created by rearranging or recombining otherwise standard components, while perhaps changing the color of a laminate stock or the like.

Today, do you want a composite stock colored in pink and purple polka dots? Order a couple of thousand and Ruger will cheerfully arrange to have them dipped. Oh yes, the new hydrographic technology makes creating complex patterns, e.g., camouflage, practical. Now the sky’s the limit for specials. There is literally no hope of amassing a collection of 10/22s that would include one of every variation produced since 1964; there must be hundreds.

Things Fall Apart (with apologies to Chinua Achebe): The Ruger 10/22 Takedown

While the variations and varieties of 10/22s are manifold, the basic rifle remained the same. Until, that is, Ruger devised a way to make the 10/22 “fall apart.” Of course, as quickly as the 10/22 Takedown comes apart, it goes back together. The takedown concept did not originate with Ruger; Ram-Line, originally a small company offering replacement plastic stocks and magazines, created a very simple “takedown” kit using thumbscrews for the barrel band screw, takedown screw and barrel retainer (v-block) screws.

In addition, Volquartsen Custom offers a version of their Fusion rifle, a 10/22 lookalike, with a barrel attachment system that borrows from the AR-15. The barrel is retained by a barrel nut that screws to a receiver extension into which the barrel is slipped. The barrel nut is integral to a floating tubular hand guard. Screw the hand guard off, slip the barrel out, and you have a three-piece ensemble. The Fusion is offered in two flavors: .22 LR only, or .22 WMR/.17 HMR—the latter individually or as a package with both barrels. Of course, while it looks like a Ruger, it’s not a Ruger.

Ruger Makes a Ruger

Ruger being Ruger, of course, has taken its own innovative tack on the subject of 10/22s that break down for convenient packing, with the 10/22TD. Back in the days of railroad travel, takedown rifles were very popular for hunters who rode the rails to get to the staging areas for their hunting trips. The Savage 99, for example, was available in a very popular takedown version.

While we don’t ride the rails much anymore—well, really, hardly at all—we do have other kinds of motorized transport, whether our automobile or an ATV. Thus, it makes sense to have a more compact package to take with us on our forays. It doesn’t hurt that the Ruger 10/22 Takedown comes with a discreet carrying case that can be strapped on one’s body, backpack style, if your mode of locomotion is shank’s mare.

The 10/22TD is promising to be something of a product line of its own, with a myriad of stock variations in both composite and wood, blue and stainless barrels, threaded and unthreaded muzzles and different carrying case colors. The solidity and rigidity of the barrel assembly attachment, (which includes a wear-compensating adjustment), means that the Takedown will be as long-lived and rugged as the original 10/22 rifle.

A Milestone is Reached, and Celebrated

In 2014, Ruger celebrated the 50th Anniversary of the 10/22 in a myriad of ways. Each box is marked “50 Years of the 10/22.” The bolts in 10/22s made in 2014 are marked similarly.

There are two special models of 10/22 that are specific to the 50th Anniversary. The first is a model configured via a design competition held on the internet, wherein the finalists were judged by the web-surfing public. The 50th Anniversary Winner combined the 10/22 with the interchangeable butt-and-comb composite stock of the Ruger American bolt action rifle, adding a Picatinny rail to the receiver and a flash suppressor on a threaded barrel.

The winner’s rationale was to support youth training because he was an Appleseed Project leader. The two available lengths of pull could accommodate youth and adults of varied stature, while the two available comb heights can adapt the rifle for the included irons, or optics, as desired. The Picatinny rail makes optics installation easy. The threaded barrel’s flash suppressor protects the muzzle from the occasional neophyte’s spearing turf with the barrel.

The second special model was a Collector’s Series, wherein can be found a metal wall sign, a bumper sticker, a pin and a facsimile of the first 10/22 advertisement. While the Collector’s Series is otherwise an ordinary 10/22 Carbine with composite stock, it is fitted with fiber-optic front and rear sights.

What’s in store for tomorrow for the 10/22? There’s no way to know; Ruger listens to its customers, both distributors and you and us, the end users. There’s no telling when some great idea will come from the field; Ruger is by no means loath to give us what we want, if a business case can be made for it.

Second, Ruger is staffed with imaginative engineers and product managers, who come up with stuff we didn’t know we desperately needed, e.g., the American Rimfire interchangeable modular buttstocks or the 10/22 Takedown. Combine that ingenuity with customer input, and you get the 50th Anniversary winner, a 10/22 with an American Rimfire-type interchangeable-buttstock-module stock.

Will there be another 10/22 breakthrough such as the Takedown? We can’t say; what we can say with confidence is that Ruger will continue to mix and match components such as stocks and barrels; there are many variations of each, plus subvariants such as threaded or unthreaded muzzles, laminate stock colors, and the like.

We can expect new components, options and variations to emerge from the fertile minds of Ruger’s ever-expanding team. We know one thing for sure; the 10/22 will still be going strong for at least another 50 years.

For complete technical information, detailed photos and more background on the Ruger 10/22, get your copy of "The Ruger 10/22 Complete Owner's and Assembly Guide" at scott-duff.com.