This article, "The Pedersen Device: Its Design, Production & Post-War Issuance," is part one of a two-part series exploring the history and service of this unique technology. You can read part two, "The Post-War Pedersen Device: Infantry Testing & Ultimate Fate," at this link.

The First World War spurred colossal changes in the mechanics of warfare by, among other things, increasing the firepower wielded by low-level infantry formations. No longer were American infantry sections limited to magazine-fed bolt-action rifles (themselves a comparatively recent introduction), instead receiving Chauchat, Lewis, and Browning Automatic Rifles in unprecedented numbers. With sufficient training, these firearms, coupled with modern hand grenades and rifle grenade launchers, allowed small units to effectively fix, maneuver upon, and destroy enemy forces, even in the absence of heavy machine gun support or artillery fire, if necessary.

While the standard rifle and bayonet remained a critical component of maneuver formations, the realities of the fighting on the Western Front showed the crucial importance of continued small arms innovation. It also highlighted the need for a rapid-fire infantry firearm that a single soldier could employ without relying on supporting team members. Using World War I-era memorandums, proposals, requests and evaluations from the National Archives, digitized and made available by Archival Research Group, this article documents the development, production and ultimate fate of one device intended to ensure American soldiers were the best armed on the battlefield.

The Man & The Plan

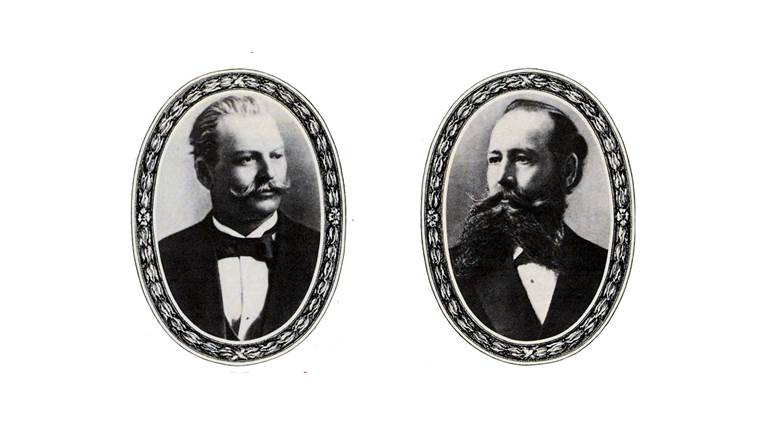

One man who stepped forth to fill the innovation gap was John D. Pedersen. While overshadowed today by luminaries such as Samuel Colt or John Moses Browning, Pedersen was a successful firearm designer working for Remington. He was responsible for successful sporting firearms produced by the company and had at least 18 patents to his name by the time America entered the First World War.

John Pedersen, while also developing a full-power semi-automatic rifle, determined that the M1903 bolt-action rifle could be adapted, using an "automatic bolt," for rapid short-range firing.

John Pedersen, while also developing a full-power semi-automatic rifle, determined that the M1903 bolt-action rifle could be adapted, using an "automatic bolt," for rapid short-range firing.

Understanding the inherent limitations of a bolt-action rifle and seeing the importance of rapid-fire firearms, he had begun work on “a light, semi-automatic infantry shoulder rifle.” Still, he had determined, at least for the present time, that it was not ready for combat use since, even if it could be made sufficiently light, “the cooling problem and ammunition supply remain unsolved.” The need for a different rapid-fire arm was borne from his study of the use of infantry rifles, where he found that at long or mid-range, a semi-automatic rifle firing full power service ammunition was not as efficient as a purpose-built and properly mounted machine gun, and “would quickly waste their ammunition without accomplishing the desired result.” However, “In fighting at short range… either offensively or defensively, infantry armed with suitable automatic rifles would have a tremendous advantage… They could quickly obtain fire superiority, rendering them secure from assault, or irresistible in attack.” Writing to his superiors at Remington in October 1917, Pedersen stated:

“Some years ago it occurred to me that all these problems could be solved by combining with the present service rifle an automatic bolt which would be inserted into the rifle on the removal of the manual bolt. This automatic bolt would be light in weight, simple, and fire semi-automatically a short-range cartridge condensed into its smallest and lightest form while possessing the necessary velocity and striking power against personnel for short-range combat.”

Finding merit in Pedersen’s proposal, Remington arranged for a secret test before officials of the War Dept. in Washington, D.C. The “Pedersen Device,” as it became colloquially known, slid into the receiver of a slightly modified Model 1903 rifle after the standard rifle bolt was removed and properly stowed by the shooter. While the loaded weight of more than 3 lbs. significantly added to the heft of the firearm, it also dramatically increased the rate of fire as it fed from a 40-round magazine and, in testing, could fire approximately 100 aimed shots a minute. Besides the increased weight, a significant tradeoff was the diminished power of the cartridge, which featured a .30-cal., 80-grain projectile moving at between 1,300-1,500 f.p.s. (this in comparison to the .30-’06 Springfield rifle cartridge with a 150-grain projectile moving at 2,700 f.p.s.). In theory, this was perfectly acceptable since the rifle could still be used with standard rifle ammunition with the reintroduction of the standard bolt, giving the infantryman great versatility in engaging targets with whatever ammunition was appropriate for the situation.

The main components of Pedersen's device, eventually assigned the nomenclature "Automatic Pistol, Caliber .30, Model 1918" consisted of the device itself, a sheet metal scabbard designed to hang from the cartridge belt, and 40-round magazines carried in a web pouch. Photo courtesy of NRAMuseum.org.

Early Demonstrations & Tests

The tests in D.C. convinced the War Dept. of its apparent utility in the ongoing conflict, and the prototype, along with an Ordnance Dept. representative, was shipped over to France the next month for examination by Gen. Pershing and testing by a board of officers. This board convened on Dec. 9, 1917, and consisted of senior officers from infantry and cavalry backgrounds and two representatives from the Ordnance Dept.

Over two days of testing, the board found that the device would provide great surprise effect against enemy troops and be useful during offensive and defensive operations. They recommended ordering 100,000 devices immediately but cautioned that they should only be put into combat service when 50,000 were ready for field use to maintain the shock effect on German military operations. Given the small number of devices (possibly only one), the composition of the board, and time considerations, the Pedersen Device underwent only limited testing in classroom and rifle range conditions, never being placed in the hands of troops in simulated field conditions.

Nevertheless, the Headquarters of the AEF quickly adopted the recommendation on Dec. 11, 1917, and the Pedersen Device soon received the formal designation of “Automatic Pistol, Caliber .30, Model 1918” from the Ordnance Dept., with rifles modified for its use being designated as “Model 1903 Mark I.”

Pedersen Production, Practical Pivots & Poor Document Handling

In January 1918, Remington was ordered to produce 100,000 Pedersen Devices, but soon after ran into a problem—the M1903 rifle around which the device was designed was no longer the most numerous service rifle being produced for overseas service. While the first regular and National Guard divisions pushed overseas were indeed armed with M1903s, most infantrymen were to be armed with the newly adopted Model 1917 rifle, based on the British Pattern 14.

The reasons for this were purely practical: the comparatively efficient and financially incentivized commercial firms producing the M1917 were turning out thousands of those rifles a day, while production of M1903s at the national arsenals amounted to a mere trickle by comparison. Between Aug. 1 and Dec. 31, 1917, the Eddystone, Winchester and Ilion rifle plants produced a total of 302,887 M1917 rifles, while Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal produced a paltry 111,808 M1903s during that same period.

When the automatic bolt and magazine were loaded in the M1903 rifle it significantly added to the weight and threw off the balance, but dramatically increased rate of fire. Photo courtesy of NRAMuseum.org.

When the automatic bolt and magazine were loaded in the M1903 rifle it significantly added to the weight and threw off the balance, but dramatically increased rate of fire. Photo courtesy of NRAMuseum.org.

As this disparity in production was only going to grow more pronounced over time, it was therefore decided that the 100,000 Pedersen Devices, plus perhaps a supplemental order of 30,000, would be sufficient to arm those formations that would retain the M1903 in the field while, in June 1918, the Ordnance Dept. ordered the creation of a Pedersen Device capable of being fitted to the M1917 rifle, with the prototype for this new model being demonstrated approximately two months later.

In August 1918, the War Dept., in a memo with the subject line “Proposed increased orders for caliber .30 automatic pistols,” approved the Ordnance Dept.’s request for permission to produce “500,000 Pedersen attachments for the 1917 rifle” to be classified as the Mark II, and that “the entire 500,000 should be ready by next March [1919] for use in the spring campaign as that is the time they will be most urgently needed at the front.” As the war ended before any significant production was completed, the contract was canceled in December 1918, since Ordnance officials had already decided to retain the M1903 as the standard service arm while functionally mothballing most M1917s and making new M1917-specific equipment unnecessary.

Despite the secrecy surrounding the development of the Pedersen Device, it is possible that Germany was aware of both the device and the desire for the Mark II production late in the war. As relayed by the provost marshal of Paris, on Sept. 29, 1918, military police officers on duty at the Casino de Paris theater found a copy of the above-quoted secret memorandum, lost by a Maj. Wright, lying on the establishment's floor. Given the amount of information contained within, should a clever German agent have come across the document, they would likely have been able to deduce the general nature of the underlying device and its timetable for employment.

The Pedersen’s Uncertain Fate In The Immediate Post-War Era

While the Pedersen Device for the M1917 never got off the ground, Remington had successfully produced 65,000 for the M1903 before that contract was cut short in March 1919. Destined for the great spring offensive of 1919 that never came, the devices and their modified rifles found themselves without a war to fight. The government found itself not only with the devices but also with 1.6 million magazines, 65 million cartridges unique to the system and more than 100,000 modified M1903 Mark I rifles.

To try and find a future use for the secret firearms, the Army convened another board in France, this time headed by Brig. Gen. Harold Fiske. The April 1919 “Fiske Board,” as it came to be known, appeared to be the most comprehensive test to that point and consisted of “a platoon armed with the device firing against silhouette targets placed to represent the enemy and then repeated the test with the same platoon armed with the Springfield rifle without the device.”

The snug fitting sheet metal scabbard would protect the device from the mud of the trenches, but added another piece of kit to hang from the already oft-overburdened infantryman. Photo courtesy of NRAMuseum.org.

The snug fitting sheet metal scabbard would protect the device from the mud of the trenches, but added another piece of kit to hang from the already oft-overburdened infantryman. Photo courtesy of NRAMuseum.org.

The Ordnance Dept. briefly considered procuring more Pedersen Devices post-war, corresponding with Remington on that point throughout the fall of 1919, with Remington quoting the government a whopping price of $40 per device. It was also in this period that official doubts about the device began to appear in earnest, with reports from the infantry and cavalry boards reporting that the weight of the device and ammunition, along with the decreased effective range, decreased striking power and the complication of operating the system severely limited the practical usefulness of the firearm. It was also noted during this time that “the devices cannot be considered as strictly interchangeable in all rifles.” This was despite attempts to eliminate up to 30 percent of devices that required additional adjustment, and advice given was that “an effort be made to keep that particular device and rifle together, rather than to attempt to use the device indiscriminately with any rifle.”

The program’s secret classification was rescinded in December 1919 “In view of the necessity for more extended information being made available in connection with the distribution of the […] Pedersen Device … .” After being offered “to various commands for riot duty and subcaliber application” in late 1919, the majority of devices and rifles were placed into storage, with their ultimate fate still undecided. The significant exception to this rule was the Panama Arsenal, which received the following equipment in 1920:

4,000 Rifles, U.S. Cal. 30, M1903, Mark I.

4,000 Pistols, Automatic, Cal. 30, M1918.

4,000 Scabbards, Automatic Pistol, Cal. 30, M1918.

800 Wrenches, Automatic Pistol, Cal. 30, M1918.

60,000 Magazines, Automatic Pistol, Cal. 30, M1918.

4,000 Carriers, Spare Bolt.

12,000 Cases, magazine.

This issue, along with more than 5 million rounds of pistol ammunition, “was meant to provide this equipment for one squadron of Cavalry and one regiment of Infantry” stationed in the Panama Canal Zone. The next largest issue was to Fort Banks, a coastal artillery installation in Massachusetts, which received a substantial 400 devices in December 1919. The remaining issue was spread across 21 other coast artillery, infantry, cavalry and artillery organizations, which received between one and 75 of the devices each.