One of the most venerable United States military arms of the 20th Century was the Browning Automatic Rifle, known to several generations of American soldiers as simply the BAR. Invented by the legendary John Moses Browning, the Model of 1918 BAR was fielded in limited numbers during the closing days of World War I, where it soon gained an enviable reputation as a rock-solid and reliable automatic rifle. By the time of the Second World War, the BAR was well-established as the U.S. military’s basic squad automatic weapon. Even with the advent of the semi-automatic M1 Garand rifle, the BAR was an integral part an American infantry squad. The later production version of the BAR, the M1918A2, saw service in all theaters of World War II and remains one of the better known U.S. infantry arms of the war.

The only other U.S. military arm similar to the BAR fielded during World War II was the Model of 1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun. It was invented and developed by Melvin Maynard Johnson, Jr., a Boston attorney and Marine Corps Reserve officer who dabbled in small-arms design in the mid-1930s. When the M1 Garand was adopted in 1936, Johnson was not overly impressed with the new rifle and felt he could develop a superior semi-automatic service rifle. Rather than base his design on gas operation, Johnson chose to utilize a recoil-operated mechanism. Johnson refined his design and was able to persuade the U.S. Army Ordnance Department to conduct a test of the rifle. In addition to its recoil-operated mechanism, Johnson’s rifle had some other novel design features including a 10-round rotary magazine that could be readily topped off (unlike the M1) and an easily detachable barrel.

Although Johnson’s rifle functioned fairly well in the preliminary tests, some weaknesses were revealed, most of which were common to any prototype. Johnson was informed by the Ordnance Department that his rifle was inferior to the standardized M1 and would not be considered for adoption or purchase by the U.S. military. Johnson felt, perhaps with some justification, that his rifle had not been given a fair trial because of institutional bias in favor of the M1, which had been developed by the Ordnance Department. The inventor was successful in having Congressional hearings held to explore the issue, but Congress declined to force the U.S. Army to accept the Johnson. Johnson tried to interest the Marine Corps in his rifle as well but, after some preliminary tests, they decided against its adoption.

While developing his semi-automatic rifle, Johnson was simultaneously working on a light machine gun, actually an automatic rifle, based on the same general operating mechanism. Both Johnson’s rifle and machine gun shared a number of components and could be easily manufactured on the same equipment. Johnson’s light machine gun design utilized the same basic recoil-operated mechanism and featured an easily removable barrel and buttstock assembly.

It had several advanced design features, including the ability to fire fully automatically from an open bolt (to help cooling while firing) and the capability to fire from a closed bolt in the semi-automatic mode (to increase accuracy). It had a straight-line stock to reduce perceived recoil and improve control during fully automatic fire. The gun had a 20-round, single-column, detachable box magazine that fed from the left side of the receiver.

Another novel design feature was that the magazine feed lips were machined into the receiver, so they were not subject to damage or deformation as were conventional magazines. This increased the reliability of the Johnson LMG because many malfunctions of automatic arms are due to faulty or damaged magazine feed lips. The magazine could be loaded by means of the M1903 Springfield rifle’s five-round charger (stripper clip). The gun could also be topped off from the right side of the receiver with single rounds or a charger, without having to remove the 20-round magazine. It was fitted with an easily detachable folding bipod.

One of the gun’s most attractive attributes was its light weight (for a machine gun or automatic rifle) of just over 12 lbs., as compared to the BAR, which weighed in at some 20 lbs. In addition to the much lighter weight, the Johnson light machine gun’s removable barrel was a distinct advantage over the BAR’s permanently attached barrel as it permitted overheated or shot-out barrels to be quickly and easily replaced. Although designated a light machine gun, it is properly classified as an “automatic rifle.” As correctly stated in the publication International Armament, Vol. II, “since the [M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun] did not use a belt feed, the Army and Marines classed it with the BAR and officially considered it an automatic rifle.”

Melvin Johnson also tried to interest the U.S. military in his light machine gun, but it was not formally tested by the U.S. Army, and its reception more or less mirrored that of the Johnson rifle. Not one to be easily deterred, Johnson went to Europe shortly before the outbreak of World War II in an attempt to market his designs to some of our Allies. Little interest was shown in the Johnson rifle, but several countries were impressed with the light machine gun. No orders were initially forthcoming, however, and Johnson returned home and continued the quest for acceptance of his guns.

Ever the optimist, Johnson formed a corporate entity, Johnson Automatics, Inc., to market his arms, and he continued to refine his semi-automatic and light machine gun designs. These efforts culminated in the development of production versions of the Johnson rifle and light machine gun, which were both given the designation “Model of 1941.”

As Johnson was finalizing development of the M1941 rifle and light machine gun, the government of the Netherlands, under the auspices of the Netherlands Purchasing Commission, contacted Johnson and requested a demonstration. The Dutch were interested in acquiring modern arms for their colonial troops in the Dutch East Indies. Johnson’s demonstration favorably impressed the them, and orders were placed for quantities of both the M1941 rifle and M1941 Light Machine Gun. Although made under contract for the government of the Netherlands, both Johnsons were chambered for the standard U.S. caliber .30 (.30-’06 Sprg.) cartridge at the request of the Dutch.

The Johnson organization acquired a former textile machinery factory in Cranston, R.I., for production of the gun.

The manufacturing entity for Johnson Automatics, Inc., Cranston Arms Co. produced both the M1941 semi-automatic rifle and M1941 Light Machine Gun under contract for the Dutch government. Limited quantities of Johnson rifles, along with a few light machine guns, were shipped to the Dutch East Indies prior to their occupation by the Japanese. Upon the fall of the East Indies, the remaining Johnson rifle and LMG production was embargoed and remained in the United States.

Although the U.S. Army Ordnance Department expressed no real interest in either the Johnson rifle or light machine gun, the U.S. Marine Corps viewed the latter as an arm that could play a role in the USMC parachute units that were being formed in late 1941. In addition to its impressive firepower and light weight, the LMG’s easily detachable barrel and removable buttstock made for a compact package, which the Marines viewed as an attractive attribute for airborne use.

The M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun weighed just over 12 lbs., had a 22" barrel and an overall length (assembled) of 42". The straight-line design necessitated a high front sight and the gun had a folding, finely-adjustable Lyman rear sight. It fired fully automatically at a rate of approximately 450 r.p.m. from an open bolt and fired semi-automatically from a closed bolt. Early M1941 Johnson Light Machine Guns were equipped with a barrel lug designed to mount the same rudimentary all-metal spike bayonet as issued with the M1941 Johnson rifle. This feature was eventually dropped and subsequent Johnson machine gun barrels did not have bayonet lugs.

Arrangements were made with the Netherlands Purchasing Commission and Johnson Automatics, Inc., for sufficient numbers of the M1941 Johnson Light Machine Guns to be acquired by the U.S. Marine Corps for issue to the parachute units. In addition, limited numbers were also acquired by the Marines for issue to a few Raider units.

The M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun’s baptism of fire in American hands occurred during the Solomons campaign in August 1942 when it was used with notable effectiveness on Tulagi, Gavutu and Guadalcanal, primarily by the USMC’s First Parachute Battalion. During the subsequent key battle of the Guadalcanal campaign, known as Bloody Ridge, the Marine paratroopers’ Johnson light machine guns were credited with laying down a defensive cross fire at a crucial point in the battle to save Henderson Field. The paratroopers would reportedly fire several magazines from their Johnson light machine guns and quickly change positions in order to confuse the Japanese and avoid enemy counter fire. The Johnson gunners typically carried four or five magazines, which were reloaded with standard M1903 Springfield five-round stripper clips. Although not officially procured by the USMC during this period, 23 M1941 Johnson semi-automatic rifles lent by Melvin Johnson to the Marine First Parachute Battalion also saw combat during the Solomons campaign.

The Johnson Light Machine Guns were used in several subsequent Pacific battles by the Marine paratroopers and a few Raider units. The campaign that saw the most extensive use of Johnson machine guns was Bougainville, the northern most island in the Solomons chain. By this time, a number of M1941 Johnson rifles had been procured for issue to the Marine parachute units and some also saw combat action on Choiseul.

While the gun’s firepower, dependability, light weight (as compared to the BAR), inherent accuracy and easily removable barrel were distinct advantages. There were some minor complaints. The Johnson’s high front sight and side-mounted magazine snagged on vegetation while moving through the jungle. The lack of suitable pouches to carry the 20-round magazines was also cited as a minor problem. A canvas backpack magazine carrier holding 12 magazines was manufactured in very limited numbers but, apparently, few were issued, and examples are very rare today. Like the M1918A2 BAR’s bipod, the Johnson LMG’s bipod was often removed, and frequently discarded, during combat to reduce weight and make the gun handier.

While the number of Johnson M1941 Light Machine Guns procured and issued by the Marines was much smaller than the number of BARs, the Johnson LMG was highly regarded by most of the Marine paratroopers and Raiders who had occasion to use it in combat. There are numerous contemporary references to the effectiveness of the M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun in Marine Corps service during World War II. A typical example is contained in an after-action report of a Marine Raider unit on New Georgia Island ,which stated:

“Johnson Light Machine Gun, M1941. Operated smoothly under adverse conditions. Very little maintenance needed. Men now armed with them wouldn’t trade them for any other. Suitable magazine carriers should be furnished.”

Another illustrative passage regarding the excellence of the M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun was contained in a report authored by Marine Lt. Col. Victor Krulak who gave a brief synopsis of the various arms used by Krulak’s Second Parachute Battalion during the Choiseul operation prior to the Bougainville invasion: “Johnson Light Machine Gun (Automatic Rifle). The most praiseworthy single weapon. It showed no weaknesses. Functioned perfectly under most arduous conditions. It is extremely light (12.5 lbs.) for an automatic rifle, which makes it ideal for jungle combat. It is short and comfortable to carry. The magazines are most rugged. It is accurate, with an easily adjustable sight and, for the jungle task, considered quite superior to the B.A.R. which is itself a splendid weapon.”

Some individuals have maintained that the Johnson light machine gun was not as reliable or durable as the BAR, but this assessment is not supported by actual field reports and documentation. In combat use, the M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun was at least as reliable as the highly regarded BAR.

Marine & FSSF Johnson LMGs

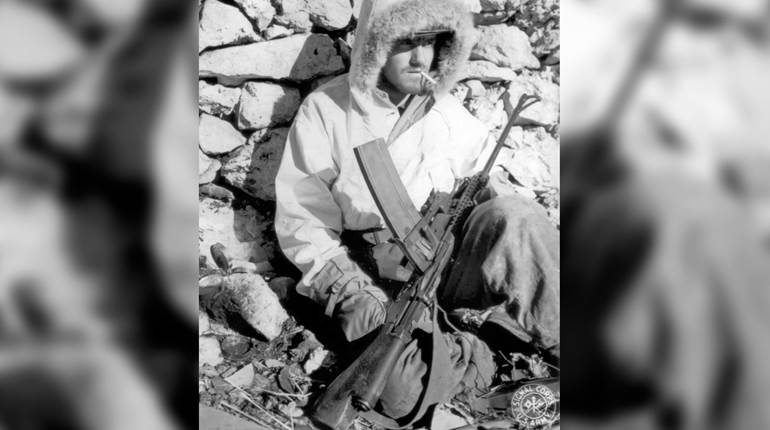

While most of the M1941 Johnson Light Machine Guns in U.S. military service were fielded by the Marine Corps, a limited number were procured by one of the most elite, and most unusual, U.S. Army units of the Second World War. The First Special Service Force (FSSF) was a joint American-Canadian outfit that was formed in early 1942 for the purpose of conducting winter warfare operations in German-occupied Scandinavia. The unit received intensive training in airborne operations, winter combat (including fighting as ski troops) and demolition. The FSSF was able to obtain several items of non-standard weaponry, including the unique V-42 stiletto.

The M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun was viewed by the First Special Service Force as an ideal arm for its purposes as outlined in a “Confidential Memo” dated February 15,1943, from Lt. Col. O.J. Baldwin, executive officer of the FSSF to Asst. Chief of Staff, G-4 which, in part, stated:

"Subject: Johnson Light Machine Gun"

"1. The 1st Special Service Force has a serious need for a lightweight machine rifle, of characteristics similar to those of the Browning Automatic Rifle, that can be carried with parachute troops in parachute operations. The weapon most nearly meeting these special qualifications is the Johnson Light Machine Gun equipped with bipod mount. This gun is now a standard item for Marine paratroopers.

“2. It is requested, therefore, that action be taken to secure for the 1st Special Service Force, by transfer from the Marine Corps, 125 Johnson Light Machine Guns, complete with accessories, spare parts, and instruction manuals, as are now furnished to the Marine Corps.

“3. The advantages of the Johnson Light Machine Gun, which are the basis for this request, are:

“a. The weight with full magazine is approximately 14 lbs. in contrast to approximately 23 lbs. for the Browning Automatic Rifle.

“b. The gun can be broken down into three pieces of a maximum length of approximately 22". “This permits it to be parachuted in the same manner as the M-1 rifle. The lightness in weight and ease of assembly (from 20 to 50 seconds) makes it an extremely valuable parachutist weapon.”

The Marine Corps approved the request for the 125 Johnson Light Machine Guns on April 20, 1943, and they were delivered to the First Special Service Force on June 29, 1943, with Johnson Automatics, Inc., handling the transfer from the Netherlands Purchasing Commission to the FSSF.

Before the First Special Service Force was fully trained and ready for deployment, the Scandinavian operation was cancelled, and the unit was eventually deployed to Italy where it played a key role in the pivotal Anzio campaign. The Forcemen (as they called themselves), and their Johnson M1941 Light Machine Guns, were credited with helping to break out of the Anzio beachhead and securing the hard-won victory. The FSSF troops were every bit as enamored with the Johnson light machine gun as were the Marine paratroopers and Raiders who used them in the Pacific. It is reported that many of the Forcemen were reluctant to turn in their Johnson light machine guns when the First Special Service Force was deactivated in the South of France in early 1945.

The conclusion of the Second World War spelled an end to active combat use of the M1941 Johnson Light Machine Guns by the American military. A few turned up in the hands of the Chinese Communists during the Korean War, and some were used by Castro’s rebels in Cuba in the late 1950s. Melvin M. Johnson, Jr., developed improved versions of his light machine gun design, but the subsequent guns were only manufactured in limited prototype numbers.

The M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun incorporated several design features which are still used on front line military arms today. Although its use was relatively limited, the Johnson was clearly ahead of its time in many ways, and it gained an enviable reputation with the majority of its users. If the Johnson Light Machine Gun had been developed as fully as the BAR and standardized by the U.S. Army and the U.S. Marine Corps, it would have played a much larger role in World War II and would undoubtedly be viewed today as one of the best Allied infantry arms of the war. Instead, the M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun, along with its M1941 Johnson semi-automatic rifle counterpart, is but a footnote to U.S. ordnance history.

Surviving examples of the former that have been properly registered with the BATFE, and eligible for civilian ownership, are quite rare and are among the most valuable, and elusive, fully automatic arms on the market today. The M1941 Johnson Light Machine Gun remains one of the least known, but one of the most innovative and effective, American arms of the Second World War.