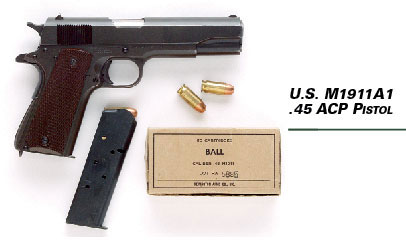

Top Photo (National Archives image): An assault boat team of soldiers from E Company, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, approaches Omaha Beach on Tuesday, June 6, 1944. A mannequin memorial to the 82nd’s John Steele hangs on the bell tower of the 13th century Roman Catholic church in Ste.-Mère-Église (below), Normandy. Sgt. John Ray, also of the 82nd, saved Steele and Pvt. Ken Russell with his .45 ACP M1911A1 pistol.On D-Day, Tuesday, June 6, 1944, thousands of American soldiers struggled on the beaches, the drop zones and in the hedgerows of Normandy. They fought with the steel of Pittsburgh and Birmingham in their hands—steel that had been fashioned into the guns of D-Day. Each rifle, pistol and submachine gun that fired shots in anger had a story associated with it. These are just a few of those stories.

It was approximately 0130 hours when the 2nd platoon of F Company, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division began jumping from C-47s. As fate would have it, the pilots overshot the assigned drop zone, resulting in paratroopers descending directly over the crossroads town of Ste.-Mère-Église. German units throughout the area had been alerted to the coming invasion by 1100 hours on June 5. In addition, the center of the town was alive with activity as German soldiers and French civilians struggled to extinguish a house fire. Among the 505th troopers who came down on Ste.-Mère-Église during the pre-dawn hours of D-Day, two men landed on top of the town’s 13th century Roman Catholic church. Pvt. John Steele snagged his parachute on the bell tower and Pvt. Ken Russell came down hard on the slate roof of the nave.

A third man, Sgt. John Ray—born and raised in Gretna, La.—landed hard in the church square just below Steele and Russell. While Ray struggled to free himself from his parachute harness, a German soldier rounded the corner of the church and shot him in the stomach with a burst from his MP40 submachine gun. Assuming he had killed Ray, the German turned toward Steele and Russell, both of whom were helpless targets.

As the German shouldered the MP40 to shoot Steele, Ray drew his M1911A1 .45 ACP pistol and shot the German in the back of the head. Steele and Russell both survived the Invasion of Normandy thanks to the actions of John Ray, who left a young widow back in Louisiana. Within a few short hours, additional 82nd Airborne paratroopers entered and occupied Ste.-Mère-Église, making it the first town in France liberated on D-Day.

At 0710 hours on June 6, 1st/Sgt. Leonard “Bud” Lomell exited his landing craft onto a narrow beach shingle at the base of a cliff that loomed above him almost six stories. As the senior NCO of D Company, 2nd Ranger Battalion, Lomell was a part of one of the most daring D-Day missions—to neutralize the guns at Pointe du Hoc. Despite enemy rifle and submachine gun fire, he slung his M1A1 Thompson and began to free-climb a runnel on the east side of the point.

A rocky promontory a few miles west of the main landing area for Omaha Beach, Point du Hoc was where the Germans had built one of the most powerful artillery batteries in the entire Seine River estuary. The battery consisted of concrete tables for six French 155 mm long-range guns called GPFs (Grande Puissance Filloux). The Germans had captured large numbers of GPFs when they invaded France in 1940. Redesignated as the model 15.5 cm K418(f), the purpose of the GPF battery was to defend occupied France. Because the guns at Pointe du Hoc were capable of placing accurate, long-range fire on both Utah Beach and Omaha Beach, the Allies planned for a special assault force to scale the cliffs and destroy the guns. This mission went to Lt. Col. James E. Rudder’s 2nd Ranger Battalion.

Using ropes, grappling hooks and ladders, the Rangers carefully worked their way up the cliff face and into a lunar-like landscape. For weeks leading up to the invasion, Allied bombers pounded Pointe du Hoc, leaving massive craters all over the battery site. Then, on the morning of the invasion, the battleship U.S.S. Texas (BB-35) fired dozens of 14" shells at it. When 1st/Sgt. Lomell crested the top of the cliff, he found German infantrymen using the craters as fighting positions, and he immediately plunged into an intense close combat environment. Moving from one crater to another in search of the GPFs, it was soon obvious to the Rangers that the guns were not there. The Germans removed them a few weeks prior because of the relentless Allied aerial attacks that had so battered the site.

As the firefight raged in the craters, Lomell soon found himself in the company of S/Sgt. Jack Kuhn, and together the two Rangers began pushing inland. When they reached the D-514 coastal road at about 0800, Lomell noticed large tracks leading into a nearby orchard. Following the tracks, the two Rangers quickly found five GPFs and, using thermite grenades, destroyed each gun’s traversing and elevation mechanisms. Then Lomell used the buttstock of his M1A1 Thompson to smash the sights. These GPFs—among the deadliest guns of D-Day—never fired a shot in opposition to the Normandy invasion.

Although the battle for Pointe du Hoc was fierce, it was not the deadliest of all of the beach sectors that saw action that morning. On Utah Beach, the U.S. Army VII Corps faced relatively light opposition and suffered comparatively few casualties. In stark contrast, though, the U.S. Army V Corps landings on Omaha Beach were opposed by more troops, more guns and coastal terrain dominated by tall bluffs. The main landing area for Omaha Beach stretched between the coastal villages of Vierville-Sur-Mer and Colleville-Sur-Mer.

The entire area was covered by a series of bunkers, artillery casemates and infantry fighting positions the Germans referred to as Wiederstandsnesten (resistance points). Each was situated to produce interlocking fields of fire with another, and each mounted arms of various types and calibers. One of the largest of these points was the sprawling bunker complex at Wiederstandsnest 62 (or WN62), which stretched from the top of the bluff down to the water’s edge. Completely encircled by barbed wire and land mines, WN62 included two casemated 75 mm guns, as well as mortar pits, trenches and machine gun nests.

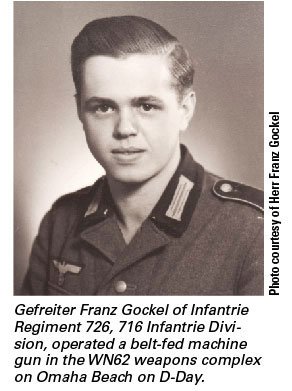

The farthest forward of all the positions at WN62 was at the edge of the sand dunes and faced toward the sea. It included an open emplacement for a 50 mm anti-boat/anti-tank gun and a semi-covered machine gun nest. Franz Gockel, a corporal assigned to Infantrie Regiment 726 of Infantrie Division 716, manned the machine gun. When assault troops began landing at 0630, Gockel loaded his belt-fed machine gun and began firing on men of the 16th Infantry Regiment/1st Infantry Division as they attempted to wade ashore.

Surprisingly, Gockel was not firing an MG42 or an MG34; instead, he manned a captured Polish CKM Wz.30. The Wz.30, chambered in 7.92x57 mm, is a water-cooled machine gun manufactured on the Browning M1917 design. It is thought provoking to consider that a version of the Browning machine gun was used on D-Day to kill American soldiers.

Although the WN62 complex accounted for a large number of the Americans killed in action on Omaha Beach, the greatest loss of life took place two miles to the west at Vierville-Sur-Mer. In front of a natural defile in the bluff that the U.S. Army code-named the “D1 Exit,” there were three WNs that could direct fire against a landing force. Because of this, the infantry company spearheading the landing in this sector suffered like no other.

At 0630, A Company of the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division began landing in front of the D1 Exit. The company landed with no tank support and had neither cover nor concealment. The result was devastating. The company landed with 164 officers and men, and in the first five minutes of combat suffered 91 killed in action and 64 wounded. The firepower of the three WNs reduced the strength of an entire rifle company to barely a handful of men. In the wake of the virtual annihilation of A Company came B Company, 116th, in their British-made landing craft.

One of the men who came ashore at that time was 19-year-old PFC Harold Baumgarten. As he went down the ramp, a machine gun bullet struck his helmet, causing some bleeding, but he stumbled on. A few seconds later, while wading through the surf, a shell fragment struck his cheek and shattered his upper jaw. In shock and bleeding badly, Baumgarten dumped all of his equipment and rinsed the blood off of his face with English Channel water. He then lifted his M1 Garand rifle to port arms and staggered forward. While still in the water, a bullet headed for his heart struck the side of his Garand. He looked down and could see the seven cartridges in the magazine through the hole caused by the enemy bullet. In that unconventional way, the M1 rifle saved Harold Baumgarten’s life. When he reached the beach shingle, he flattened out into the prone position and spotted a German soldier moving at the top of the bluff. He took aim with his damaged M1 and pulled the trigger. The rifle broke apart in his hands. It was the only shot Harold Baumgarten fired at the enemy on D-Day.

Despite very serious wounds, he continued to advance, moving up and over the bluff, only to be wounded three more times. He was evacuated the following day and survived multiple operations. After the war he became a physician, and he returns to Omaha Beach every June 6.

During the pre-dawn hours of June 9, the entire 1st Battalion of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division crossed the flooded Merderet River north of a farm manor called La Fière and commenced a flanking attack on German positions at a tiny village named Cauquigny. On the American far right, one squad of C Company of the 325th advanced across a sunken cattle path, well within the field of fire of a German MG42 team. As dawn broke, it became obvious the attack had stalled and the glider infantrymen needed to pull back.

As the men attempted to withdraw, the MG42 pinned them down in a ditch alongside the sunken path. With bursts of 8 mm bullets slicing the morning air all around them, the men could not return fire without exposing themselves. In the middle of what seemed to be a hopeless situation, 23-year-old PFC Charles N. DeGlopper took the initiative.

A native of Grand Island, N.Y., DeGlopper was big: he stood 6 ft., 6" tall, weighed 240 lbs., and had size 13 feet. He obviously reached the sober realization that the only way his comrades stood a chance was if someone were to draw the enemy’s fire while they made their escape. Unhesitatingly assuming that responsibility, DeGlopper shouted to the others to go and that he would cover them. Then he went to work.

Standing in the middle of the road and shoulder firing his 19.4-lb. M1918A2 BAR, DeGlopper instantly attracted the enemy’s attention. The Germans directed their fire at him from several sources, and within moments, he was hit. Ignoring his wound, he remained on his feet and continued firing at the enemy. Then, DeGlopper was hit by German bullets again and began to stumble. Although he dropped to one knee, he steadied himself and amazingly still found enough strength to load a fresh 20-round magazine into his BAR. He then leveled it at the enemy one last time. Weakened by his grievous wounds, he continued to fire burst after burst at the Germans while the men of his squad dashed across the sunken path. While still kneeling in the middle of the road, DeGlopper was finally killed outright by German bullets.

By drawing the enemy’s fire, he saved the lives of all the men of his squad. DeGlopper was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for what he did that morning near the La Fière causeway. It was the only Medal of Honor received by a soldier of the 82nd Airborne Division during the Normandy campaign.

The Normandy invasion is replete with remarkable stories of courage and sacrifice. Men like John Ray, Bud Lomell, Charles DeGlopper and Harold Baumgarten answered the call and shouldered the rifle during the great crisis. They came to France that summer to liberate an oppressed people and continue the important work of ridding Europe of Nazism. Some of them never left the France they came to save.