From Arms and The Man, December 15, 1921

In spite of the excellent performance of the Springfield Rifle in establishing new records at the recent National Matches, the history of firearms plainly indicates that this arm which we now think so perfect must in a few years bow to the mark of progress and be superseded by a weapon of even greater effectiveness. Many military experts believe that the next advance will be the adoption of a semi-automatic, or self-loading, shoulder rifle. The advocates of this view state in support of it that in the past few years several successful semi-automatic hunting rifles have been produced; that self-loading shotguns have become popular; that the revolver has gradually given way to the automatic pistol; and finally, that, after exhaustive tests and mature consideration, the Government has adopted the automatic as the service sidearm and confirmed its choice by the test of battle.

The critics of the self-loading rifle state that with our present Springfields we can get enough rapidity of fire to heat up the gun and to quickly use up the ammunition, and that greater rapidity is unnecessary. In reply, the advocates of the semi-automatic say that battle accuracy, and not rapidity of fire, is the main advantage of the proposed weapon. The big difference between the bolt action gun and the self-loader is that when you fire the bolt gun you must then lift up the handle, draw back the bolt, push the bolt forward, and turn down the handle, before the arm is again ready to fire; while with the self-loader all you have to do after firing one shot is to pull the trigger to fire again, as the arm has reloaded itself in the meantime. To visualize the advantages of such a weapon, suppose yourself in a war, occupying an advanced post. Over the top of the enemy's trenches, 400 yards away, a gray helmet is dimly visible. You take careful aim, and then fire. To your disgust the shot strikes low. Hoping that your intended victim has not noticed your attentions, you quickly pump the bolt of your Springfield, thinking to get in another shot. Of course if you are one of the fortunate few who have benefited by Camp Perry's grind of rapid fire, you will perform this operation smoothly and quickly, but if you are of the mass of untrained citizens who make up the bulk of our national defense, you will yank wildly at the bolt of your rifle, at the same time taking your eye from your objective and making a movement that may well betray your presence. Then you look back for your target. He has seen your motion and has gone; or, perhaps, he quickly makes you his target. With a self-loading rifle this is quite a different story. You aim at the enemy and fire; the shot strikes low; without taking your eye from your sights, or your sights from your target, you alter your aim and again press the trigger, with every probability of success.

That our own high officials attach great importance to the future of such a weapon is shown by the fact that the War Department has officially invited the inventors of the country to submit guns of this type. The Government circular states in part: "The rifle must be of a self-loading type, adapted to function with cartridges not less than .25 caliber or greater than .30 caliber, of good military characteristics and preferably to fire the U.S. cartridge, caliber .30, model 1906. It must be simple and rugged in construction, and easy of manufacture. It should require but little more attention than the regular service rifle when placed in the hands of the average soldier."

A test of rifles submitted in response to the circular has just been completed by a board of officers which met at Springfield Armory on November 28th.

For many years the attempt to design a self-loading military rifle has received a large amount of attention from European gun designers. Both Mauser and Von Mannlicher worked for years on this problem. Many experimental models were produced and tested, but most of them were either too heavy and clumsy, or too delicate and complicated. In the earlier models, the power to operate the bolt action was obtained either by allowing the barrel to recoil relative to the rest of the mechanism, or by drilling a hole in the barrel and allowing part of the powder gas from each shot to escape through this hole and act on a piston, which in turn operates the gun. Both of these systems have the disadvantage of adding parts which increase the weight of the already heavy military rifle.

In order to bring the weight back to normal, many designers reduce the barrel to a very small size, which is a serious mistake, because a small barrel is not only inaccurate on account of excessive vibration, but is also extremely susceptible to overheating, a fault which the self-loading rifle, with its high rate of fire, should especially guard against. A further disadvantage of the recoiling barrel system is the danger of getting a construction in which the motion of the barrel will interfere with the accuracy, while against the gas operated system we must record the difficulty of cleaning the gas cylinder and the gas port in the barrel.

However, in spite of these troubles, there are several guns of both types in successful use at the present time. Prominent among the representatives of the recoil operated group is the Remington auto-loading rifle. This gun, which was invented by John Browning, has been popular for over a decade. In spite of the recoiling barrel, the construction is such as to give excellent accuracy. However, the weight of the barrel is not great enough to allow sustained fire without heating. This does not impair its usefulness as a hunting rifle, but would cause trouble in military service. The Remington and Winchester shotguns are also examples of highly successful recoil operated guns.

The Mondragon rifle, of which a limited number were used by the Germans in the late war, and the French St. Etienne model, are examples of gas operated guns which have at least passed the experimental stage far enough to have been used to a certain extent in warfare.

Another system of operating automatic guns which was the merit of simplicity, is the blow-back, or inertia system, in which a heavy breech-block is used, which is not locked against the explosion at all, but is merely held in place by a spring. When the gun is fired, the bullet starts forward and the breech-block starts backward at the same time, but as the breech-block weighs so much more than the bullet, it moves correspondingly slower, and gives the bullet time to be out of the gun before the breech opens. Most automatic pistols are built on this system, as well as the .22 caliber automatic rifles. The trouble is, that with high-powered cartridges the breech-block must be very heavy to make the gun safe and to prevent ruptured cartridges. With the .30 caliber Government cartridge, the breech-block of about 25 pounds weight is necessary. The Winchester self-loading rifles are of this type. The weight which adds the necessary inertia to the breech-block is carried to the forearm of the gun. The cartridges for this gun are of a special type with a straight case and a quick burning powder.

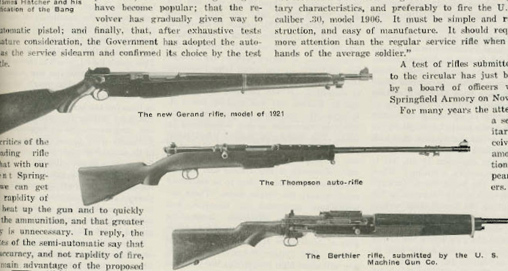

From the foregoing remarks the reader will not be surprised to learn that the recent developments in the field of automatic weapons have been towards the production of new methods of obtaining power which will not involve the difficulties mentioned above. Only one of the rifles just tested followed the previously accepted principles of operation. This was the Berthier rifle, submitted by the U.S. Machine Gun Co. This gun is a very clever gas-operated weapon following the principles of the Berthier Machine Rifle, which passed a successful test at Springfield in 1917. This gun went through both this year's test and the test of 1920, and appears to function well. Its main disadvantage seems to be its rather awkward shape.

One of the guns which was tested last year was (and which was being rebuilt at Springfield Armory for test this year, but was not completed in time), obtains its power from a small cap over the muzzle. The cap slides on the barrel, and has a hole in its front end large enough for the bullet to go through. When the gun is fired the bullet passes out through the hole and the gases which follow draw the cap forward a short distance. This motion of the cap is transmitted through a rod to a lever which throws back the breech-bolt, ejecting the empty shell. A spring returns the breech-bolt and cap, at the same time reloading the gun. This is called the Bang system of operation. It was patented many years ago by Maxim, and was used by Soren H. Bang as the operating principle of a rifle which he submitted to our Government in 1911. The Bang gun showed great reliability, and passed the most creditable test of any automatic arm submitted before the war. However, it was clumsy and difficult to make, and the barrel had to be extremely small to keep the weight down. These disadvantages prevented its adoption, but nevertheless its excellent functioning through the various tests earned a high degree of admiration for the gun and its inventor. The system is extremely flexible, and will shoot high pressure or low pressure cartridges equally well in the same gun. The muzzle cap reduces the recoil about 20 percent, and cuts down the flash. It is also said to reduce to some extent the sharpness of the report. Against these good points must be set down the fact that it adds a few ounces to the weight, and makes the attachment of a bayonet difficult.

Last year Springfield Armory redesigned the Bang gun, and entered the new model in the test. The modified gun was simple, light, compact, and of pleasing outlines. It functioned well, and showed promise of success, but broke during the endurance test and was withdrawn. The board recommended that the rifle be redesigned for the purpose of perfecting it and accordingly an improved model was started but was not completed in time for the test, though work is being continued on it.

Besides the modified Bang, the Ordnance Department submitted to last year's test a second type of rifle which was built by Mr. John C. Garand, a mechanical engineer employed by Springfield Armory. This gun is operated on a novel principle originated by Mr. Garand, which was none of the disadvantages of the systems heretofore mentioned. Mr. Garand's principle of operation consists in allowing the primer of the cartridge to push back the firing pin, and in making this backward motion of the firing pin unlock and open the breech-block. At first this may seem a difficult thing to do, but when it is remembered that with the service pressure the total backward force on the primer is over 1,800 pounds, it will be seen that by making a heavy firing-pin, which just fits the head of the primer, a very short backward motion of the primer of not over 2 or 3 one-hundredths of an inch will put a large amount of kinetic energy into the heavy firing-pin, which is sufficient to operate the gun. During the test of 1920, 3,000 rounds were fired by this gun before the board, which demonstrates without question the possibility of operating a gun on this principle.

However, the test developed some structural weaknesses in the design, and this gun was also redesigned. This year's model is far simpler than the one submitted last year. However, this year's Garand gun, like the Modified Bang, was not completed in time for the test. It was first assembled and fired during the week that the board met, and as was to be expected, some adjustments were found necessary. The gun in its unfinished state was demonstrated by firing, but was not submitted to the regular test.

Work on the gun is being continued. Its light weight, neat appearance, and simplicity of mechanism have elicited much favorable comment, but of course final judgment must be reserved until after the gun is proved by an official test.

Still another rifle which shows a radical departure from the old accepted lines is the Thompson auto rifle, which was entered by the Colt's Patent Firearms Co., both in this year's test and in the test of 1920. This gun employs for its operation the Blish principle of adhesion, which was discovered and patented by Commander Blish of the U.S. Navy. This principle was first observed in working with large guns. The breech-blocks of these guns are held in place by an interrupted screw. It was observed that in firing very light charges the breech-blocks had a tendency to unscrew from the pressure on the front, while in firing heavy charges this tendency was absent, instead of being greater, as we would naturally expect. Commander Blish undertook experiments to determine the cause of this peculiarity and came to the conclusion that while the inclined surfaces would slide under moderate pressures, they would adhere and remain immovable when the pressure on them is high. Further research developed the fact that by selecting the proper angle for the pitch of the thread, a breech-bolt of the interrupted screw type could be built for the Springfield Rifle that would hold fast under high pressures and fly open under lower ones. While the bullet is in the rifle, the pressure is high enough to lock the rifle shut, but when the bullet has left and the pressure has dropped the right amount, the mechanism opens and throws out the empty shell. This is the principle of the Thompson auto rifle designed by Gen. John T. Thompson, retired, the father of the present Springfield. It goes without saying that a mechanism of this kind is free from the disadvantages mentioned as applying to the gas and recoil operated types. It remains for the board to answer the question as to whether or not a satisfactory gun is in sight as a result of the test.