This article was first published in American Rifleman, August 2009

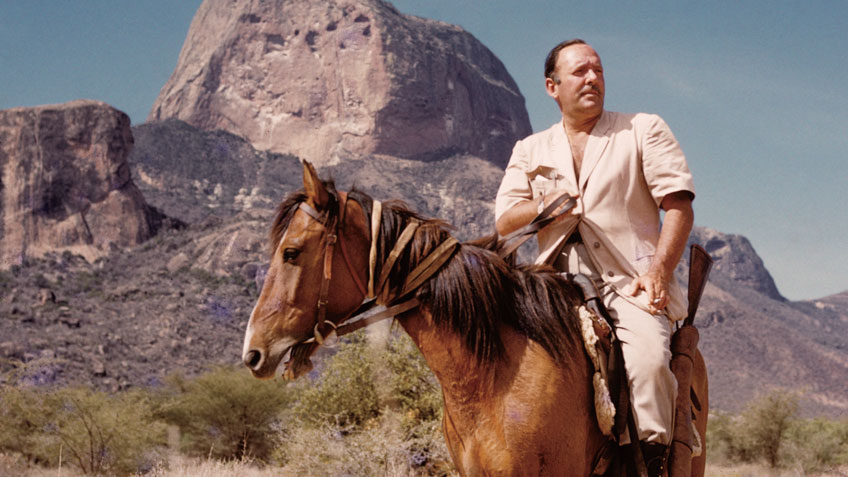

Haraka, how about one last East African safari together? I don’t know how long the local politicos will continue to welcome me here in Kenya, and you have pretty well decided to head for pastures anew farther south,” Bob Ruark suggested to me shortly before Kenya’s independence back in 1962. “It will be a sort of Kwaheri safari (farewell safari),” he added.

“Sounds good to me. And incidentally, the game department has decided to open up a large area of the Northern Game Reserve to safari hunting up in the Northern Frontier District (NFD). It’s an immense tract of bush, and there’s been no legal hunting there since the turn of the century,” I said. “There’s reputed to be some big tuskers roaming that country. It will be safari hunting with a difference, however, as no vehicles are allowed in the hunting area, so it will be a ‘horse-and-camel safari’. Maybe we should give it a try—could be a lot of fun! Have you ever ridden a horse?”

“Let’s do it, just the two of us, no damn photographers or women, and let’s make the whole purpose of the safari a big elephant—a hundred-pounder or better,” Bob replied enthusiastically. “And that bit about riding a horse … . I’m as at home in the saddle as I would be on a bar stool at the Twenty-One Club.”

“Safaris going into the ‘horse-and-camel’ area will be allowed to use vehicles to get to a designated base camp, but from then on all hunting will be done on foot, or from horseback. If we move camp to another site, all our camping equipment will be carried by camels,” I explained to Bob. “I think it’s a splendid idea, and something that neither of us has experienced before.”

I lost no time in booking the vast area east of the Mathews Mountain range for a month. The camels and horses, together with their handlers, were available for hire from the local native council. We’d begin hunting on the first day the area opened to safari hunting, making us the first safari party ever to hunt in that area. Bob and I both became more and more enthusiastic at the thought of hunting through that vast wilderness on horseback, with our camel caravan following behind.

The plan was for me to set up a base camp, which I could get to by vehicle, a few days before Bob’s arrival to ensure the horses and camels had been brought in and were in good shape. Bob would fly in to a small bush airstrip near the base camp, where I would meet him—we’d be ready to start hunting the next day.

When I arrived in our hunting area, I found that 10 days previously, heavy, unseasonal rains had swept through the country. Many roads and tracks had been washed away, pools of water were everywhere and the bush was so green and thick I could barely see through it. Elephant sign, however, was everywhere. It was mostly from breeding herds, but I figured with so many jumbos in the vicinity there must surely be some bulls, too. At least, I fervently hoped so, because unless we struck it lucky early, I realized that with the present conditions it could be a hard hunt, indeed.

The crew set up the base camp with everything in good order. Our horses and camels, together with their handlers, had arrived at the campsite and looked to be in fine shape—although the horses were clearly not thoroughbreds. I now awaited Bob’s arrival while gleaning all the information I could about any elephant with big tusks from the local Samburu people. The Samburu are a nomadic tribe, similar to the Masai, who roam throughout this piece of country tending their livestock.

Bob flew in on schedule, and we spent the rest of the day settling in, checking equipment and firing the rifles to make sure all was well. Finally, we made a short scurry into the bush on horseback to try out our mounts and procure some camp meat for a rather large retinue of staff.

Leaving camp the next morning, Bob and I were mounted on horseback while our gunbearers, guided by Salee, the head camel handler, walked ahead of us. We plunged into a sea of green bush, and right away came upon a breeding herd of elephants accompanied by a couple of young bulls carrying no more than 30 pounds of ivory per side. We scanned several more breeding herds that first day with similar results. On one occasion, an angry cow made a furious demonstration in our direction, charging right up to us and then stopping dead in its tracks, slamming its ears together in front of its head. The cow stood stock still staring directly at us for what seemed like hours, but was in fact seconds, before wheeling round to rejoin the herd. For those few brief, but intense, seconds, I thought I would have to shoot it. I also realized that if we carried on messing around with the breeding herds, inevitably in self-defense, we’d have to shoot an elephant we didn’t want.

We found tracking to be a waste of time owing to the movement of so many elephants throughout the area. Any interesting tracks we tried to follow were quickly obliterated by elephant herds walking on top of them. I soon realized our best chance of locating a big bull would be by glassing with powerful binoculars. The summits of numerous kopjes (hills), some of which were several hundred feet high and towering above the sea of green bush, would make excellent places from which to spot.

Early the next morning found us perched on top of the nearest kopje, with our nags, in the care of a groom, cropping the green grass below us. The kopje was fairly high, and we marveled at the show of elephants we could see all around us in the surrounding bush. There were literally many hundreds of elephants, mostly breeding herds, from which we could easily pick out the bulls by their larger size. It became a matter of patiently watching and waiting for the bull to lift its head and hoping to get a glimpse of the ivory.

For the next 10 days we spent hours sitting atop various kopjes in the broiling sun, but we saw new elephants every day and hoped that a big bull might suddenly appear. Then one day I was focused on a particularly large-bodied bull about a mile away. When the bull lifted its head, I caught a glimpse of a long, almost purely white tusk. I pointed out the animal to the gunbearers and we noted that the bull stood near an unusually shaped tree at the base of which we could discern a splash of scarlet … obviously a beautiful desert rose. We would use those two landmarks to orient ourselves when we climbed down into the ocean of bush to go have a closer look.

Clambering down from the rocks, we set off in the direction we’d fixed in our minds, but it was quite different once we were in the thick stuff from the way it had appeared from our lofty perch. Heaps of elephant dung were everywhere, and the buzz of many dung beetles flying to and fro in search of the aromatic piles was constant. Several times it was necessary to detour around cows and calves, and we nearly ran afoul of a rhino that fortunately only snorted loudly at us before blowing and taking off with indignation.

As if directed by radar, Salee led us to the tree we’d marked from the kopje, and nearby we found the large tracks of a big bull—undoubtedly the one we’d spotted from the hill. The tracks were fresh and easy to follow since the bull hadn’t gone far, but it had chosen a particularly thick patch in which to enjoy a midday siesta. There was little wind as we crept in as quietly as possible. Eventually, I saw its outline through the leafy curtain between us—the bull was close. We moved a little to one side, and I could vaguely make out the one fine long white tusk. “Is there a second tusk?” became the burning question in my mind. Just then it moved its head and I glimpsed the other tusk, long and unbroken—a perfect match with the other one. The pair appeared, however, to be somewhat thin and only mildly tapered to a point. Clearly, they would make a superb pair of trophy tusks, but would they make our self-imposed target of a hundred pounds each?

The heart/lung area was clear, and I was aware that Bob had raised his double rifle and was aiming at the bull. I put my hand on his barrels and whispered, “Wait, I can’t be sure he’ll go a hundred pounds.” I could see that the bull was a younger animal and could possibly provide an unpleasant surprise if a large nerve was removed from the tusk—the larger the nerve, the bigger the nerve cavity, which means less ivory.

Turning around, I whispered to Bob, “Let’s leave him. I can’t be sure.” We crept out of the thicket for a short distance and stood looking back at where the bull was standing. Whether it heard us, or possibly got a whiff of us, I don’t know, but it started moving forward. As the bull crossed a gap in the bush, and its tusks became clearly visible, they looked wonderful. Again, I considered whether it would perhaps make the “hundred-pound” mark.

The bull settled down again nearby, and back we went creeping right up to within a few yards of it. Again, I could not bring myself to tell Bob to “Go ahead, take him.” The possibility of yard-long nerve cavities haunted me. After several minutes, which seemed like ages, I peered intently at what I could see of the tusks. As I weighed them in my mind on the scales of many years’ experience, I felt a nudge and an urgent whisper in my ear from Bob—“D*mn it, Haraka (Harry’s Swahili nickname meaning ‘the one in a hurry’), lets sh*t or get off the pot.” In spite of the tense circumstances, Bob’s way of putting it amused me, and it broke the spell.

“Okay, let’s leave him,” I said. “We’ve still got time on our hands.”

The conclusion of “The Kwaheri Safari” with Robert Ruark as told by Harry Selby will appear in the next issue of American Rifleman.—The Eds.

The Guns And Loads Of The Kwaheri Safari

Our choice of guns had been influenced by the fact that they would have to be carried in scabbards on our horses, so the number of firearms would by necessity be limited. We settled on taking only four rifles.

Bob would use the delightful little double by W. J. Jeffery in .450/400 caliber that he had purchased several years earlier from Westley Richards of London. The rifle had been previously owned by W.D.M. “Karamojo” Bell and was sold as part of his estate after his death. Bob also bought Bell’s Rigby .275. The intention was to give the two rifles to our firstborn, his godson, Mark Selby. I kept the guns for Mark until he was old enough to handle them, and in the meantime, Bob used them when he came on safari in Kenya.

The .450/400 is a fine caliber and was popular in India. It is a lightweight, handy rifle and mild-mannered in recoil. In the hands of an experienced hunter the .450/400 will do anything required of it. In fact, when my son Mark became a professional hunter, he used it very successfully for years as his back-up rifle.

The early African hunters, however, regarded it as a bit light for Africa’s dangerous game under difficult conditions, and it lost popularity in favor of the larger calibers, such as the .470 and .500 Nitro Express. It is an excellent choice for any lady hunter who might hanker after a double. For the duties this safari required, Bob carried 400-gr. Kynoch solids for the .450/400.

I carried my treasured .416 Rigby, which I had acquired almost by accident. Toward the end of a safari back in 1949 in Northern Tanganyika with Donald Ker and Chris Aschan, my fine Rigby double .470 had been accidentally damaged beyond repair. I needed another heavy rifle in a hurry for my next safari and naturally looked for another double, preferably another .470. But the only rifle I could find was a .416 Rigby, which someone had ordered but abandoned at Shaw & Hunter, a Nairobi gun shop.

The rifle was built on a standard Mauser action, of which I was skeptical. It fed rounds perfectly, however, when I cycled cartridges through the action rapidly. Given our time constraints, I had no option. I bought the .416 Rigby as a stopgap, with the intention of replacing it with another double .470 as soon as possible. I never did, and I might add here that through many years and many hundreds of rounds fired through it, that standard Mauser action never gave the slightest hint of trouble.

I knew the .416 Rigby rifle and cartridge by reputation, but nothing prepared me for the performance, which became apparent as soon as I began using it. The striking “knockdown” power, the incredible penetration with Rigby’s excellent solids and the flat trajectory all combined to make this, in my opinion, the perfect professional hunter’s rifle. When I shouldered the rifle, it seemed to become an extension of my arm. There was no way I would have replaced it with another double, and after a number of years my gunbearers regarded it with awe; they called it the “Skitini,” unable to pronounce “Four-sixteen.”

I am sure they attributed my success in bowling over all kinds of wounded dangerous game either “coming or going” entirely to the “Skitini” and believed that if I merely pointed it in the general direction of whatever needed to be laid low—the “Skitini” would do the rest.

In time I abandoned carrying soft-nose bullets for the .416, for the ones available from Kynoch tended to break up. The only possible use for a soft-nose bullet would be lion, and I found that the .416 rolled lions over with a solid pretty well anyway.

—Harry Selby