Imperial War Museum imagesDirector Peter Jackson, the man behind The recent film adaptation of JRR Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings," decided to take on a project to gives voice to those British soldiers that fought in the Great War. I'd heard about

"They Shall Not Grow Old" and feared that it would be released only in England. The premier happened at and in partnership with the

Imperial War Museum in London.

Thankfully, that film has made it to our shores. Jackson digitally remastered the herky-jerky, hand-cranked film of the day and paired it with the voices of soldiers who served in the war many decades later. I missed out on the first round of tickets here in Virginia, but I have two seats in the front row for this weekend.

As someone who has studied the Great War, in particular its infantry arms, I have a feeling I know what I am going to encounter. I have friends who have seen it, and they came back to me with questions about the guns used by the “Tommies” more than a century ago, whose faces fill the screen and voices resonate from the speakers.

But this was a war that was dominated by the water-cooled, belt-fed machine gun. For the British--and I am told that this gun makes a cameo—it is the “grand old lady of no man’s land.” And that is the Vickers medium machine gun (shown above and below). This is a gun that was based on the original Maxim gun, invented by Sir Hiram Maxim, and adopted by Germany. For some reason, likely because of the arsenal that probably made most of them, British soldiers, particularly of the World War II generation, came to call them “Spandaus.”

It was the belt-fed machine gun, as well as quick-firing artillery, that drove men into the earth on the Western front. A continuous network of trenches stretched from the English channel all the way to the Swiss border. To raise one’s head up above the parapet of the trenches was to invite death.

Machine guns, properly handled, firing on the flanks of an enemy advance, could literally destroy an entire battalion of infantry in a matter of minutes. And it happened over and over. Given a continuous supply of ammunition and water, kept in a jacket around the barrel to keep it from overheating, the gun could be fired continuously. I’ve heard one account on the Somme on July 1, 1916, in which the German gunners fired so much they actually had to change the barrels of their machine guns. Not an easy job and one that is indicative of a lot of rounds being fired at the enemy.

But the British had perhaps the best gun of its class, at least until John Moses Browning introduced the

U.S. Model of 1917 (above), and that is the Vickers. And those guns were handled by the Machine Gun Corps, which professionalized the science of being an "Emma Gee." Essentially, the Vickers is a lighter and just as—if not more so—reliable version of the Maxim in which the lock was inverted and some weight shaved off. This is a gun that would serve well into the Cold War.

The infantryman’s best friend, though, was his rifle. And for most British and Commonwealth troops it was the

Short-Magazine Lee-Enfield. It was called “short” because it was not the long infantry rifle that you see in the

Boer War, the so-called "Long Lee-Enfield." No, this was a compromise between a short carbine and a rifle, intended for

general-issue to all troops, including infantry and cavalry.

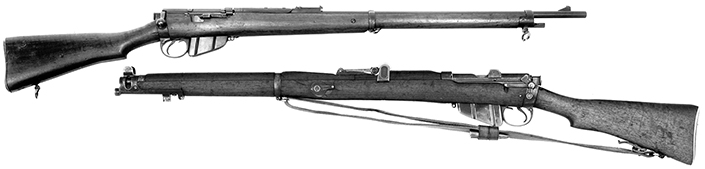

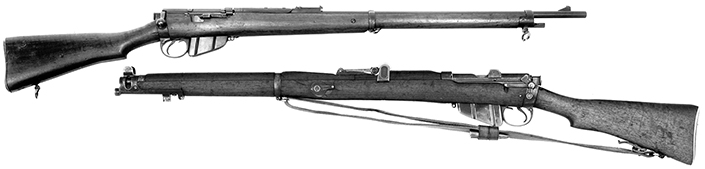

(top) Magazine Lee-Enfield Mk I* “Long Lee” (btm.) Short, Magazine, Lee-Enfield Mk III

(top) Magazine Lee-Enfield Mk I* “Long Lee” (btm.) Short, Magazine, Lee-Enfield Mk III

By the time of the Great War, the Short, Magazine Lee-Enfield Mk III was perhaps the best rile for the job. It was a bolt-action rifle that cocked on close, and was fed by five-round stripper clips into a 10-round magazine. This gave the British soldiers more firepower than any other nation, as most Mauser-based designs held only five rounds. The gun was fitted with a 17” sword bayonet, which grabbed the attention of generals and military theorists, especially in France, but proved to be of somewhat limited use as even reaching the enemy trenches through belts of barbwire, continuous machine-gun fire and artillery was easier said than done.

The length of the SMLE Mk III’s bayonet was increased to make up for the rifle’s shorter overall length. In this 1918 photograph, Scotsmen of the 6th Btn. Seaforth Highlanders root German troops out of their bunkers at bayonet point.

It is believed that more than 2 million Lee-Enfields were made during the war, and issued all across the empire to both British and commonwealth troops. The

SMLE was a very forgiving gun when it came to the filth and mud of the trenches. It’s a gun that would work in even the worst of conditions.

The rear locking lugs of the SMLE gave it an advantage over its contemporaries as it was less prone to jamming in the muck and mud typical of trench warfare during World War I.

The rear locking lugs of the SMLE gave it an advantage over its contemporaries as it was less prone to jamming in the muck and mud typical of trench warfare during World War I.

The British also had probably the best light machine gun of the war, at least until the John Moses Browning-designed Model of 1918 Browning Automatic Rifle arrived. It too was an American invention, fully developed by Colonel Isaac Newton Lewis on the principles set out by Dr. Samuel McLean, the

Lewis light machine gun (below) was and arm that gave endemic fire power to the British infantry platoon. Gas-operated and air cooled (it had an aluminum radiator inside its barrel jacket), the gun fed from a 47-round top-mounted magazine, often described as a pan. While the British army was slow to realize the importance of the light machine gun, it was the use of the Lewis gun and sections of men with grenades, called "bombers," and rifle grenadiers that lead to very effective infantry tactics late in the war.

The Lewis, weighing in at about 27 lbs., could hardly be called light today. But what it did was work. And the Lewis was made for the British at both Birmingham Small Arms and at Savage in Utica, N.Y.

Lewis gun image courtesy Rock Island Auction

When it comes to handguns, the main sidearm British tank crews in a machine gunner was the Webley revolver. At first it was the birdshead grip Mark V, but in 1915 the British adopted the square-backed Webley Mark VI. Chambered for the .455 Webley, the theory was the heavy slow-moving bullet would put a man down. The thing about the Webley is, like the Lee-Enfield, it a very reliable arm in filthy conditions, made from robust parts. The big, top-break Webley allowed mud and grime to not interfere with its basic operation.