When I got a text yesterday about the passing of Gaston Glock (1929-2023), a Beatles line popped into my head immediately. “I read the news today, oh boy,” which which is from the song “A Day in Life.“ We knew it was coming, obviously. The man was 94. And what a shadow he cast.

What a life Gaston Glock had. Growing up in the ashes of Germany during and after the Second World War, he became an engineer in a new field called plastics. We call it polymer now. Polymer is a mixture of any two materials, but it was the bonding of plastic to metal that makes him a “Jeopardy” answer.

What Glock did was use that material combined with steel to make arguably the most ubiquitous handgun of all time. Steel was still the main component for barrels and slides, but necessary pieces of steel for gun’s operation were molded to polymer here and there, permanently. Heresy in the ‘80s, but as common as dirt today. Well, Heckler & Koch had done it on the frame with the VP70 more than a decade before, most of it anyway, but no one paid attention. Sorry to my friends at H&K.

Glock started with simple things, curtain rods, bayonets and entrenching tools. The future was polymer mixed and bonded with traditional steel, making both perhaps better than the sum of their parts.

Then he found out about an Austrian military pistol contract. He went and asked questions of users and other engineers, and he developed what is now likely the greatest handgun of all time, the Glock 17. As one of the world's greatest fans of the John Moses Browning-designed M1911, it hurts to admit that Browning‘s century of dominance has been usurped by an almost-accidental pistol design. Right place, right time.

Glock’s importance cannot be overstated. There’s even a book written about the company and its rise by former Wall Street Journal reporter, Paul Barrett called "America’s Gun." (I should know. I reviewed it for the Washington Post). It’s not American. Both Gaston Glock and his pistol are uniquely Austrian. But its success in America is what propelled the Glock pistol to legendary status. Americans made Glock a household name; not stallions.

There were many players through the tempestuous rise of the Glock, but it was the inherent solidness of the design, its ergonomics, its features that propelled it to stardom with American law enforcement, and then the hearts of American shooters. Glockophilia remains rampant.

There are many Glocks, ranging from the thick to the thin, but I would argue that America’s gun is actually the 9 mm G19. I think I’m one of the few I know who doesn’t carry one every day. It is the F150 of handguns, like it or not. Numbers don’t lie, whether I agree with them or not.

I saw my first one in 1988. It was at a gun show, and it looked like nothing else. The basic design was pure genius. And it was adaptable, having been chambered in everything from 9 mm to .45 GAP to 10 mm (anyone else remember .40 S&W?). In terms of function, basically, there isn’t a tinker’s damn worth of difference between all of them. Well, obviously the .22 has to be different because it’s blowback, not recoil-operated. They don’t look dissimilar.

They can be taller, shorter, thicker, thinner, black, green or brown (sorry, I mean, FDE), but they remain essentially the same gun with different cuts on the inside of the slide as the cartridges are stripped from the magazine, but the basic principle of its operation remains unchanged from when they first arrived here in 1986. They make minor frame modifications, they add grooves, and take them away, they change the stippling, they make a dimensional change to stampings, and they call them “GENS”— but they retain a commonality that even Henry Ford would have appreciated.

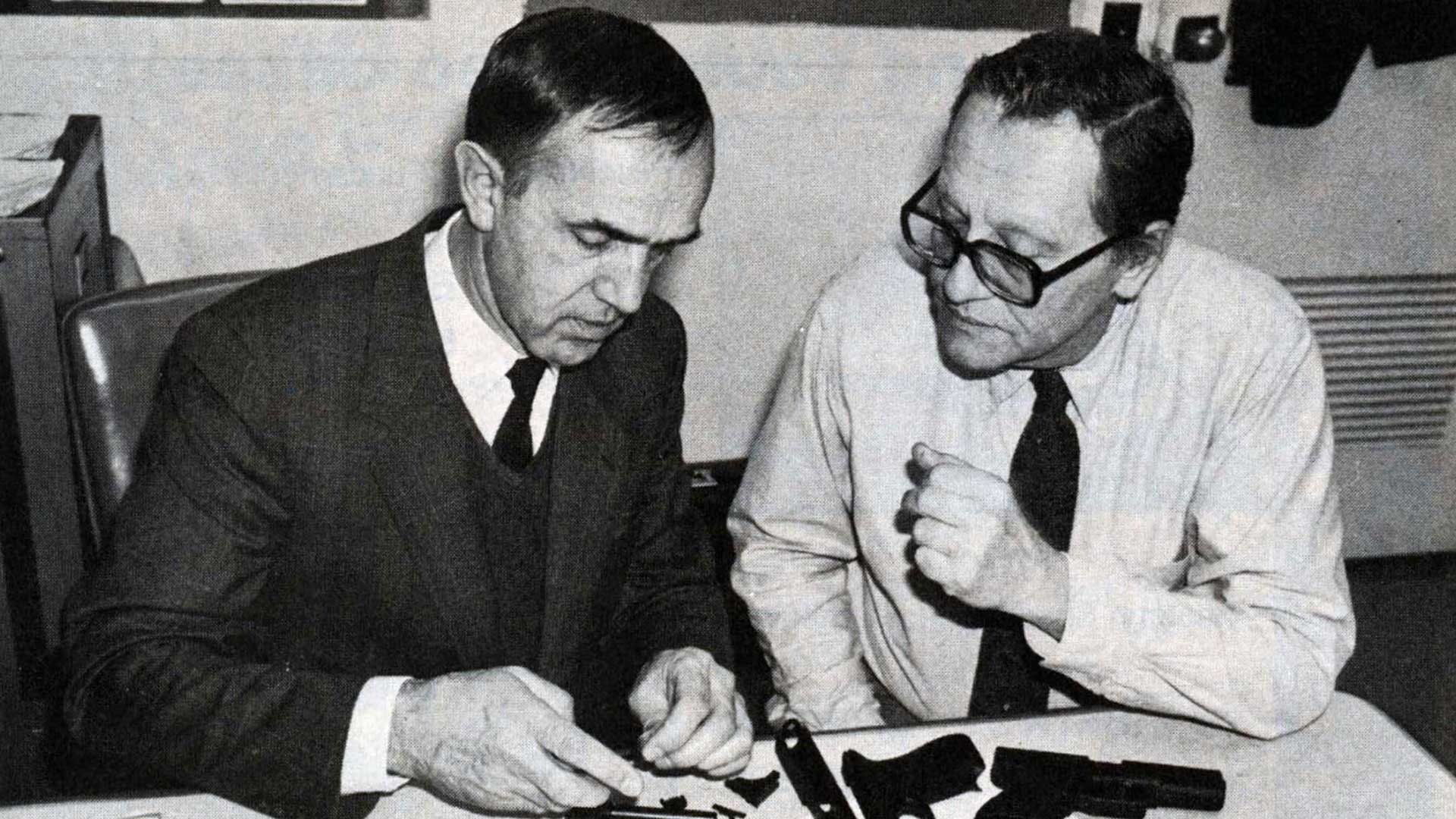

There was a magnificent article on the first Glocks by my former boss, Pete Dickey, the longtime technical editor of American Rifleman. Titled simply "The Glock 17 Pistol," it is worth reading. Because if you are one of the many owners of the Glock pistol, you need to know what his company faced at its very beginnings in the United States. Of course, the anti-gunners wanted to ban it, simply because they didn’t understand it. And I am not sure the shooting public at the time understood it either. The rumor mill at the time was delicious. Libyans wanted it, God knows why. "It could slip through an airport metal detector!" its detractors claimed. As Pete proved, the only way that was going to happen was if the machine were not turned on, or the operator asleep. The Glock, no matter how you slice it, or X-ray it, is a gun. An excellent one.

It was the Glock’s trigger system, with the safety in the trigger blade and a consistent pull and weight for every shot, that led to its ascendancy. It’s way easier to train on one trigger pull, time after time, and I’m not even sure that even then younger Gaston Glock understood that in terms of developing pistol proficiency, but he had the genie in the bottle. Easier to master, easier to train, utterly reliable, it was the gun of the future, and it owned or at least had a seat at the table in the present not long after its arrival.

In the early days, the marketing was cutting-edge, the packaging was as modern as Tupperware, and I even used a discarded G17 box with a .355" hole in the side to carry sandwiches in the ‘90s.

I think most overlooked was the genius of the original magazine. Even today, gunmakers will introduce a new gun, and they will just punt to the Glock magazine. Why fight city hall or an entire culture? They might be able to do something different, but they aren’t going to really do it much better. Glock changed a culture, then owned it going forward.

I met Gaston personally a few times, as well as his family, his son and daughter, in receiving lines and awkward meetings; he seemed to be an Austrian gentleman, an engineer with all that entails, on the quiet side, but always thinking. I would call him a practical genius, a man who rose to his time and made it his own. Farewell, Herr Glock. You left a legacy like no other.