A century ago, President Woodrow Wilson, who called the United States “too proud to fight,” asked Congress for a declaration of war. It came on April 6, 1917. It was a war the nation was unprepared to fight. The regular U.S. Army was pitifully small, even when bolstered with the National Guard. The U.S. Army would swell eventually to 4 million men in uniform, with 2 million sent to France with American Expeditionary Force (AEF). And they needed guns—rifles, handguns and machine guns.

Thankfully, there were decision-makers willing to take a risk. Despite the conservatism of the U.S. Ordnance Dept. under Brig. Gen. William Crozier, Secretary of War Newton C. Baker was more than willing to mix things up. Adopting the U.S. Model of 1917 Rifle—with three idle factories that had produced the British Pattern 1914 in .303 British—was an important step in making sure enough rifles would be available. But how to bolster handgun numbers for the rapidly expanding U.S. Army? Total production of the “U.S. Pistol, Caliber .45, Model of 1911,” a handgun this magazine's predecessor declared "The Greatest Pistol in the World,” stood at around 75,000. Colt, of course, was the primary maker, but Springfield Armory had just shut down its M1911 line in order to focus on the U.S. Model of 1903 Springfield rifle. Springfield’s tooling eventually was sent to Remington–Union Metallic Cartridge in Bridgeport, Conn., but that would not be enough. Not nearly enough.

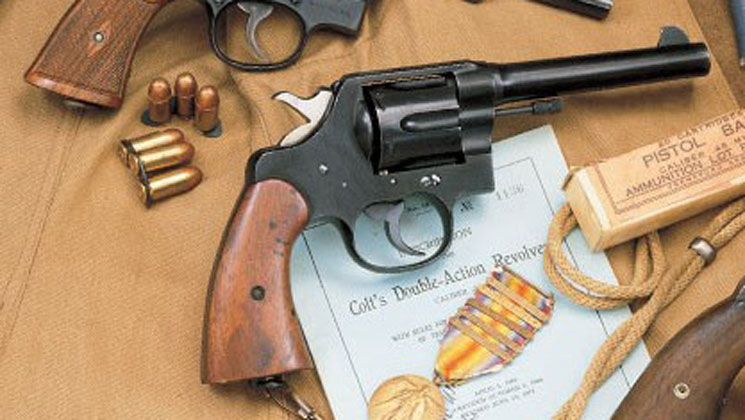

Along with the M1911 pistol, U.S. military adopted the “Caliber .45”cartridge—a round we know better today as a .45 ACP. It turns out that there are more platforms that could fire the .45 ACP than merely the M1911. Two great names in American gunmaking—in revolver making—stood up to supply additional handguns to the Doughboys heading for France. It seems just as Remington and Winchester had been making rifles for the British, Colt and Smith & Wesson had been making .455 revolvers for them, too, and the tooling and trained workforce were in place.

Smith & Wesson in Springfield, Mass., along with Springfield Armory, had been working on how to adapt its popular large, N-frame Hand Ejector to take the .45 ACP starting in about 1916. The problem with the .45 ACP is that it is a rimless cartridge designed to feed in a semi-automatic pistol from a detachable box magazine. How does one feed, fire and eject such a cartridge in a revolver, which up until that time had been pretty much exclusively the purview of rimmed cartridges?

By putting a step into each chamber in the revolver’s cylinder, they could obtain the proper headspace on the case mouth (although the early Colt M1917s didn’t have the stepped chambers). But how to get them in and out? The answer came from Joseph Wesson, who oversaw the development of what we know today as the half-moon clip. A piece of stamped sheet steel, the half-moon clip snapped over the extractor grooves of three .45 ACP cartridges. Not only did that allow for ejection, the extractor star simply lifted out the entire half-moon clip instead of the individual cases, but it was also form of speed loader. Doughboys could jam two half-moon clips into the cylinder of the swing out revolvers instead of fumbling with six individual cartridges. According to Smith & Wesson historian Roy Jinks in The History of Smith & Wesson, the first .45 Hand Ejector U.S. Service Model of 1917 was completed on Sept. 6, 1917. Too, Colt adapted its New Service, a big, heavy double-action that was rugged and reliable for the service cartridge.

Both the Colt and Smith & Wesson, with 5½” barrels and six-shot cylinders, were adopted as the “U.S. Model of 1917 Revolver,” one name for two distinctly different guns. And they served well in the trenches of France. In total 151,700 Colts were procured as were 153,300 Smiths. Had the war gone on into 1919, which American planners believed it would, there would've been more M1911s from companies, such as North American Arms in Quebec, Canada, flowing to the troops in France.

But the war ended on November 11, 1918. And Smith & Wesson and Colt Model of 1917 revolvers went into storage. When United States entered another global conflict a generation later, those revolvers were ready to serve yet again.