This article appeared originally in the January 2007 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

One of the most innovative but sometimes overlooked arms inventors of the late 1930s and 1940s was Melvin Maynard Johnson, Jr. Scion of a prosperous New England family, Johnson was a graduate of Harvard Law School, practiced law in Boston and was commissioned in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve in 1933.

Johnson’s affinity for firearm design dated from his teens. He even wrote some technical firearm articles for national magazines in the 1930s. He followed the development and subsequent adoption of the M1 rifle quite closely and had numerous qualms regarding the Garand’s basic design. Johnson believed that the M1 had a number of serious flaws, including its gas system, en bloc clip and suitability for mass production, and he felt he could design a better rifle. Johnson tinkered with several potential mechanisms and eventually settled on a recoil-operated action. While Johnson was developing his semi-automatic rifle, he was also working on a selective-fire light machine gun that utilized the same general mechanism as the rifle and shared a number of components.

Johnson’s Model of 1941 Semi-Automatic Rifle and Model of 1941 Light Machine Gun did offer some advantages over other contemporary military arms and attracted the attention of several friendly foreign nations, even though they did not gain U.S. military acceptance before the United States’ entry into World War II. On Aug. 19, 1940, the Netherlands Purchasing Commission placed an order for 10,500 Johnson rifles and 500 Johnson Light Machine Guns. All were chambered in .30-’06 Sprg. They were primarily intended to arm the Dutch colonial troops in the East Indies against the pending Japanese threat.

After Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Marine Corps procured a limited quantity of Model of 1941 Johnson Light Machine Guns from the Netherlands Purchasing Commission for use by the fledgling Marine parachute units that were formed in early 1942. In early 1943, a few hundred Model of 1941 Johnson rifles were also acquired from the inventory of embargoed Dutch guns. Some saw limited use in the Solomons campaign but were withdrawn from service after the Bougainville campaign. Some were ordered to be destroyed “in theater,” and the balance were carried back to the United States and later turned over to the Dutch. A few U.S. Marine Raider units were also issued M1941 Johnson Light Machine Guns, and 125 were procured by the U.S. Army’s elite “First Special Service Force,” which used the Johnson LMGs with notable effect during the pivotal Anzio campaign in Italy. Except for limited issue to the small USMC parachute units, Johnson rifles were not utilized by American troops.

Although the Johnson rifle and light machine gun played only minor supporting roles in World War II, the existence and general details regarding these two Johnsons have been known for many years. Their distinctive appearance and interesting design are instantly recognizable.

Even though it was significantly shorter than the Johnson M1941 rifle (top), the .30-’06 chambering of the Johnson Auto-Carbine (center) meant that it had to be much larger and heavier than the U.S. M1 Carbine (bottom). The Auto-Carbine blended parts and features from the Model of 1941 Rifle and Light Machine Gun into a compact package.

The Johnson “Auto-Carbine”

In addition to these well-known Johnson arms, there was an arm envisioned and designed by Melvin Johnson, Jr., that combined the best features of his M1941 rifle and LMG. However, this design, the Johnson “Auto-Carbine,” was never developed beyond the prototype stage and is all but unknown today.

The genesis of the .30-’06 Sprg. Auto-Carbine occurred when Johnson Automatics, Inc., of Cranston, R.I., was manufacturing the M1941 Semi-Automatic Rifle and M1941 Light Machine Gun for the Netherlands Purchasing Commission. The typical East Indian was a small-statured individual, and the full-length rifle could be a bit unwieldy because of its overall length and weight. Johnson believed that a shorter, lighter and handier rifle might appeal to the Dutch for use by their troops garrisoning the East Indies. To this end, he and his design team developed an unusual semi-automatic that was, almost literally, a cross between the M1941 rifle and the M1941 LMG. Johnson designated the gun as the “Auto-Carbine.” It is reported that the Netherlands Purchasing Commission supported the development of the new design but was non-committal regarding the potential for any future orders.

Johnson discussed the Auto-Carbine during the time of its development at the Rhode Island factory in a Providence Journal newspaper article titled “Johnson Creates Unique Firearm.” The article stated, in part:

Shorter and lighter than any comparable weapon now in existence, the gun can be fired at the rate of one aimed shot per second for the first 11 shots. Capt. Melvin M. Johnson, Jr., its designer, has fired 100 unaimed shots in 100 seconds, feeding a new clip at the end of each five shots. Two clips may be loaded in the gun at one time and it is also possible to load a single shot into the barrel.

The gun was designed by Johnson on the request of a country for which his concern is manufacturing automatic rifles and light machine guns. Although under his contract with the government of that country he must refrain from disclosing its name, it has been reported that the country is the East Indies Netherlands. It is believed that the prospective purchaser sought the lighter and shorter guns because of the short stature of its native troops.

The new gun, which has been manufactured in its entirety at the Cranston plant, is of .30 calibre, the same as the Springfield rifle and weighs 8¾ pounds. Its firing capacity is equal to the much-discussed Johnson rifle and its maker says it is easier to control than the rifle. Its accuracy, he says, is “substantially” as good as the rifle.

“I call it a carbine,” said Capt. Johnson, who holds his commission in the Marine reserves, “because everyone would begin to holler if I called it a rifle with that straight stock. It is a sub-machine gun with a rifle’s power.”

The designer allowed the reporter to fire the weapon in the big steel shed which formerly was used as a foundry by the Universal Windings Company. Flame and steel flashed from the muzzle as fast as you could pull the trigger although the recoil caused it to jerk against the shoulder; there was little upward lash. Johnson said the straight stock—the same (style) stock that is used on his light machine-gun—aids in keeping the gun on the target.

The semi-automatic gun is slightly lighter than the Springfield bolt action rifle and is five inches shorter than the Springfield, being 38 inches overall. It has a muzzle velocity of 2700 foot seconds which may be compared with the 800 foot seconds velocity of a sub-machine gun. The extreme range of the gun is 3000 to 5000 yards.

Capt. Johnson pulled the gun apart in a few seconds, using the steel nose of a cartridge to slip the mechanism that released the barrel. It was hard to believe that a weapon that could stand the terrific shock of an exploding bullet could be made to fall apart so easily. A few deft twists and the gun was back together again, and with a clip fed into its rotary magazine, it again blazed at the target. The barrels of the rifle, machine gun and carbine are interchangeable.

The carbine, which is air-cooled, has an extremely high front sight which is matched by a collapsible rear sight. For combat purposes no adjustment is necessary in the sight up to 300-400 yards.

Capt. Johnson has been working on the new gun for several months, improving it to the point where a sample could be sent to the foreign country which contemplates its purchase. …

“If I had an Army,” the captain said, “I would give some of the men light machine guns and the rest of them this carbine. Our light machine gun weighs only 12½ pounds without the mounts and can be used as a rifle. … With that machine gun and the carbine you would have two light weapons with terrific firepower.”

The prototype semi-automatic Auto-Carbine utilized the M1941 Johnson rifle’s 10-round rotary magazine but strongly resembled the M1941 light machine gun in the general configuration, including the “straight-line” design, folding adjustable rear sight and high front sight. The resulting design was more compact than either the Johnson rifle or light machine gun and had almost a bullpup configuration. It was a very attractive gun with good handling characteristics and impressive performance. The Auto-Carbine’s rotary magazine could be easily reloaded by the ’03 Springfield’s five-round stripper clips or could be topped-off with individual rounds.

The standard 22" Johnson LMG barrel was used on the Auto-Carbine. The full-length barrel eliminated the loss of velocity and increase in muzzle blast that would have occurred had it been fitted with a shorter barrel. Also, the use of standard components was intended to reduce production costs and simplify logistics. Despite the use of some standard Johnson rifle and LMG components, many of the Auto-Carbine parts, including the receiver, safety, rear sight, stock and buttplate (among others), were specifically made for the Auto-Carbine and were not interchangeable with either the LMG or the rifle. It weighed about 8¾ lbs. and was approximately 38" in overall length.

Only five Auto-Carbines are known to have been fabricated by Johnson Automatics. The tops of the receivers were roll-stamped with the standard M1941 Johnson rifle markings. The serial numbers were individually applied and had an “S” prefix (for “Sample”) with the five numbers presumably running consecutively from “S-1” to “S-5.”

Each of the five examples differed in some regard, as would be expected of prototypes. For example, a couple of the early examples had grooved fore-ends and a slightly different configuration on the top portion of the receivers as compared to the final one or two prototypes made. Serial number S-5 utilized a standard M1941 rifle fore-end, and the top of the receiver had an integral platform for protection of the rear sight when in the folded position. Some examples of the Auto-Carbine are pictured with a bayonet lug on the barrel, and others are shown without them. This was simply due to the fact that the Auto-Carbine used standard M1941 LMG barrels, and earlier barrels had bayonet lugs, while later barrels lacked this feature.

As was Johnson’s practice, he gave all of his guns a “pet” nickname. For example, Johnson christened his semi-automatic rifle “Betsy” and the Light Machine Gun “Emma.” A massive 20 mm aircraft cannon he developed for the Navy was called “Bertha.” Johnson referred to the Auto-Carbine as “Daisy Mae.” None of Johnson’s memoirs or other writings reveals his inspiration for these nicknames, although at least a couple would seem obvious.

Famed frontiersman Davy Crockett supposedly called his rifle “Old Betsy,” which may have led Melvin Johnson to give his first rifle the same moniker. The name “Emma” for the LMG was almost certainly derived from the British military’s use of the term “Emma Gee” during World War I to denote Machine Gun or “MG” (M=Emma; G=Gee). The 20 mm aircraft cannon was dubbed “Bertha” in a likely reference to Germany’s massive howitzer of the First World War called “Big Bertha” (supposedly after Gustav Krupp’s wife). One can speculate about the sleek, attractive Auto-Carbine’s nickname of “Daisy Mae,” but the logical assumption is that it was inspired by the buxom girl of the same name featured in the “Li’l Abner” comic strip popular at the time. One of the Auto-Carbine prototypes, presumably number S-3, had “Daisy Mae the 3rd” neatly stenciled on the right side of the buttstock.

The Johnson Model of 1941 Rifles and Light Machine Guns saw service with elite American troops during World War II. Not so well known is the light and handy Johnson Auto-Carbine. It could have been one of the most interesting infantry arms of World War II, but now it is a footnote in firearm history.

Harry Torgerson & The Auto-Carbine

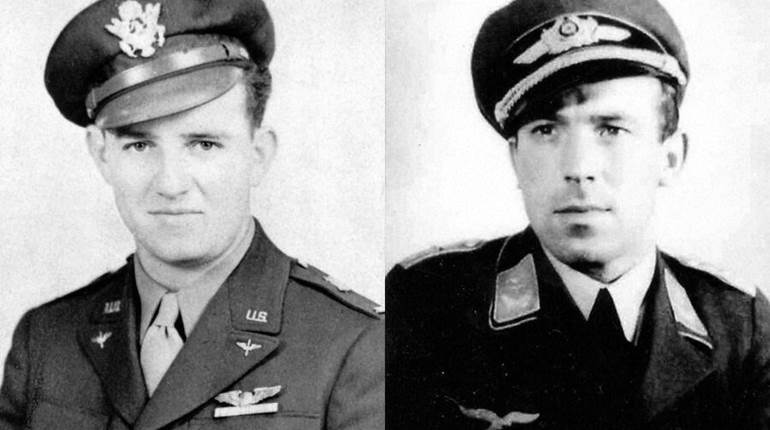

While the Auto-Carbine was under development, Marine Corps officer Harry L. Torgerson visited the Johnson factory in Rhode Island. Torgerson was the liaison between the Marines and Johnson Automatics. Torgerson’s father, Martin Torgerson, received the Medal of Honor during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. In September 1941, then-Lieutenant Harry Torgerson made a parachute jump and performed demonstration firing with the Johnson LMG for the Marine Corps Equipment Board, which resulted in the acquisition of some for the new parachute units then being formed. During World War II, Torgerson was awarded the Silver Star for heroic action in the early Solomons campaign. He was a strong proponent of Johnson arms and corresponded throughout the war with Melvin, extolling the virtues of Emma and Betsy.

During one of Torgerson’s several trips to the Cranston factory, he was allowed to handle and fire one of the experimental Auto-Carbines. He was immediately smitten by Daisy Mae but was told that under no circumstances would the Auto-Carbine be lent or sold, since it was still under development. Apparently Torgerson was persuasive enough to convince Johnson to part with one of the neat little carbines, and the Marine paratrooper carried it overseas.

Torgerson posed with his personal Auto-Carbine for several photos, including one outside his tent on Bougainville. Interestingly, photographic evidence confirms that he had possession of two different Auto-Carbines at various times during his Marine service. The first type, pictured in several photos including the one on Bougainville, was an earlier pattern with a grooved fore-end and no receiver rear-sight platform.

The later pattern was pictured on the bunk next to Torgerson at Camp Pendleton, Calif., on Feb. 10, 1945, the day he left the Marines (with the rank of lieutenant colonel). This gun, which was almost certainly serial number S-5, had the integral receiver-sight platform and the M1941 rifle-pattern fore-end as found on the last one or two Auto-Carbines manufactured. That would seem to suggest that Torgerson exchanged the earlier Auto-Carbine for the later pattern during one of his visits to the Johnson factory.

Since Torgerson retained this Auto-Carbine after he left the Marine Corps, this would indicate that Johnson either sold or gave him S-5. Torgerson’s was only the Johnson Auto-Carbine believed to have permanently left the Johnson factory and the only known extant example. The Auto-Carbine apparently remained in Torgerson’s possession until his death in 1958.

Although the Johnson organization used images of the Auto-Carbine in some of its magazine advertisements during World War II, no orders for Auto-Carbines were forthcoming, and any further developmental work on the gun ceased before the end of the war.

In late 1946, Argentina expressed an interest in Johnson’s arms, and Johnson fabricated a single prototype he designated the “Model 1947.” While specific details are sketchy, it apparently bore little resemblance to the Auto-Carbine but shared some features with the Johnson Model 1944 LMG.

Argentina apparently declined to purchase any, and the “M1947” rifle never went into production. In any event, the post-war years were not kind to the Johnson organization. The entity filed for bankruptcy and was liquidated in early 1949.

The Johnson Auto-Carbine is a fascinating and innovative semi-automatic that possessed great handling characteristics and excellent accuracy in a compact and handy package. Had Johnson received more “official” support for it, and had he been able to put it into mass production, the Auto-Carbine could well have proven to be one of the most interesting military small arms of World War II.

As it turned out, as attractive and appealing as Daisy Mae may have been, she was destined to remain in the shadows of her better-known siblings, Betsy and Emma. The Johnson Auto-Carbine is a classic example of a great design that could have been but, unfortunately, never really was.