The world of the military M16 and, by extension, the civilian AR-15 market, has become dominated by M4-style firearms. This means, in the broadest sense, a 14.5" or 16" barrel and a telescoping buttstock. The utility and do-all capability of the M4-style carbine is hard to deny, and its ubiquity makes it easy to forget that the AR-15 started out as a 20"-barreled rifle as opposed to the more dominant present carbine form. But the “full-size” M16/AR-15 has both a storied history and some distinct advantages that make re-visiting the “rifle-length” AR a worthwhile journey.

Most civilian shooters’ experiences with rifle-length ARs are limited to heavy-barreled match or varmint-hunting rifles—the first being a style brought to the civilian market by Colt in 1986 with its AR-15A2 “H-BAR.” While heavy barrels have the potential for amazing accuracy, their heft results in a front-heavy rifle that can tip the scales at nearly 10 lbs. In contrast, M16s and the earliest AR-15s feature a light barrel profile (the difference in weight between an M16A4 and an M4 is only 1 lb.), which yields completely different handling and balance characteristics than an H-BAR rifle.

Recently, rifle-length ARs have regained popularity, with manufacturers including Colt, FN America, Bravo Co. USA and Palmetto State Armory building ARs with the 20" “government-profile” barrel of the M16A2. Whether your purpose is hunting, target shooting or self-defense, there are three distinct advantages of the rifle-length AR over its shorter-barreled siblings—ballistics, reliability and durability.

First, let’s look at the ballistics. The M16’s 20" barrel has a 200-f.p.s. advantage over the 14.5"-barreled M4 when shooting M855 ammunition. In my testing, using Federal’s XM855 ammunition, a 20" barrel recorded about a 150-f.p.s. advantage compared with a 16" barrel, the common length for civilian carbines. For the carbine, that means about a 5 percent loss in velocity. The muzzle energy difference is about 125 ft.-lbs. or 10 percent.

For reliability and durability data we can look to tests conducted by the U.S. military, which give an edge to the M16 over the M4. The main reason lies in the gas system. The “rifle-length” gas system of a 20" barrel is 5" longer than the “carbine-length” gas system used on all 14.5" and many 16" M4-style carbines. Due to the drop in pressure over this longer distance, the gas port on a rifle can be larger, which results in a larger volume of lower-pressure gas heading back to the action. The extra length of the gas tube also means the velocity of the gas is slower when it reaches the bolt carrier. This means less force and heat on the working components of a rifle’s action. In contrast, the shorter length of a carbine gas system means the bolt is unlocking sooner, while chamber pressure is higher, which results in more stress on bolt lugs and extractors.

While the contemporary M4-style carbines have evolved into a highly reliable platform, it was a process that was not without its teething problems, a path marked by the necessity of innovations such as mid-length gas systems, extra-power extractor springs, modified feed ramps and H (heavy) buffers. The bottom line is that, for the first three decades of its existence, the M16/AR-15 rifle, and its 5.56x45 mm NATO cartridge, were developed and refined around a 20" barrel. Anything shorter is a compromise.

To examine the story of the 20" rifle in U.S. military service we can look at two current models that bookend the M16’s service history. The Brownells Model BRN-601 mimics the earliest M16 adopted by the U.S. military. On the other end is the FN 15 Military Collector Edition M16. With its flat-top receiver and Knight’s Armament rail system, the rifle is a semi-automatic-only clone of the last M16 adopted by the U.S. military as a general-issue infantry rifle.

As Gene Intended It: The Brownells Model BRN-601

The origin story of the M16/AR-15 is well-known. Starting in the late 1950s, Eugene Stoner’s original 7.62x51 mm NATO-chambered AR-10 was refined by ArmaLite engineers Robert Fremont and L. James Sullivan into the AR-15 to meet the demands of the U.S. Army’s Small Caliber, High Velocity (SCHV) project. The AR-15 design retained the 20" barrel of its AR-10 parent.

The U.S. Army would start testing the AR-15 by late 1958, but it was the Air Force that was the early adopter, purchasing 8,500 AR-15s in 1961. The Army officially adopted the rifle in 1963, designating it the “M16.” The new M16 was 4" shorter and 3 lbs. lighter than the M14 then in service. Its size was comparable to the iconic M1/M2 carbine, then a favorite among South Vietnamese troops and U.S. advisors in the escalating Vietnam conflict, with the M16 coming in just 2" longer and 4 ozs. heavier than the carbine.

In 1959, ArmaLite sold the manufacturing rights of the AR-15 to Colt. The earliest Colt-production AR-15 was known as the Model 601. Fewer than 15,000 601s were made by Colt between 1959 and 1963. Most went to the Air Force, with the remainder used by the Army and the Navy SEALs.

In early 2018, gun parts megastore Brownells announced that it would begin selling complete “retro” AR rifles. Its models included four AR-15s (replicas of the Colt 601, XM16E1, M16A1 and XM177E2) that represented the variants available during the Vietnam War, and two .308 AR-10s.

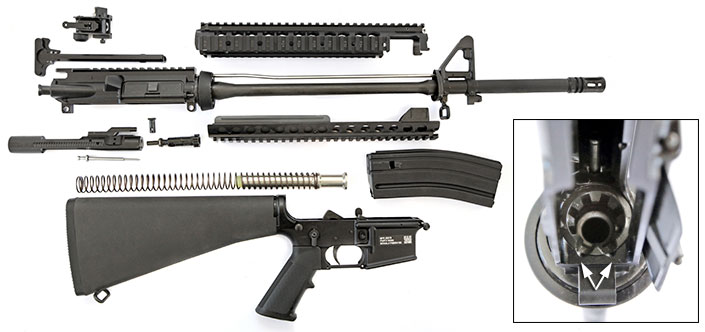

The BRN-601 is a pretty close replica of America’s first issued M16, from its triangular-shaped charging handle to the open-pronged “duck bill” flash hider. The rifle’s “slabside” lower receiver has no fence around the magazine release button or a housing for the pivot pin detent and spring (the 601’s pivot pin has a built-in detent and is not captured). There is no forward-assist device and no trapdoor in the buttplate because the early “maintenance-free” M16 wasn’t issued with a cleaning kit. Brownells even supplies the rifles with an early-style “waffle”-pattern 20-round magazine.

For the black-rifle purist, there are a few quibbling points. The selector and rear takedown pin lack the proper “divots,” and the ejection-port cover, magazine release and bolt release are of a later style, as are the rear sight directional arrows, which are molded into the carry handle instead of on the sight wheel. The original 601 barrel has a 1:14" twist, whereas the Brownells rifle has a 1:12" twist. And the BRN-601’s green polymer furniture doesn’t quite match the green-paint-over-brown-fiberglass look of the original 601.

Still, the result is very close to Eugene Stoner’s original design concept. Stoner explained many of these elements in his interviews with firearm expert Edward Ezell in the late 1980s. The 601’s “A1”-style aperture rear sight is adjustable for windage only. The front post adjusts for elevation. According to Stoner, the military had originally requested a fixed, nonadjustable sight on the rifle. Their experience in World War II showed that soldiers tended to fiddle with the adjustment knobs on the rear sight of their M1 rifles during lulls in combat, leading to a loss of zero. ArmaLite’s compromise was a sight that could be adjusted, but not easily.

The 601 also notably lacks a forward assist. Soon after it adopted the M16, the Army saw the need for a bolt-closing device, as the rifle’s nonreciprocating charging handle can only be used to pull the bolt to the rear. The XM16E1 added a forward-assist device on the right rear of the upper receiver, and the design was standardized in 1967 as the M16A1. Stoner was clear in his belief that the forward assist had no place on the AR-15 design.

“The rationale was if the weapon was dirty enough or has sand or dirt or mud or something in it and doesn’t close, the first immediate reaction should be to open the bolt and try to find out the cause of it, and not beat it shut and then find out you’ve got a disaster on your hands,” Stoner pointed out to Ezell.

But by then, the rifle’s design was long out of Stoner’s hands. The Colt 601 had launched the M16’s career with the U.S. military. Nearly 4 million M16s of all types of would be produced during the Vietnam War, the majority by Colt, with smaller numbers coming from Harrington & Richardson and GM’s Hydra-Matic Division.

The Ultimate M16: The FN 15 Military Collector M16

After the Vietnam War, the U.S. military never stopped tinkering with the M16 design. By the early 1980s, the Marine Corps was experimenting with an updated M16, called the M16A1E1. Among the rifle’s improvements were re-designed furniture, with a round handguard and a 5/8" longer buttstock, and, much to Stoner’s chagrin, a fully adjustable rear sight with click-adjustment knobs. Stoner grumbled to Ezell that the update was “arbitrarily” heavier and “more of a target rifle than a combat rifle.”

The E1’s barrel, while thin under the handguard like the original M16, was thicker from the front sight base to the muzzle. The rifling was a faster 1:7" twist to utilize the newly adopted 62-gr. M855 ammunition. The E1’s most infamous new feature was its three-round burst mechanism, which was meant to help servicemen fire shorter, more accurate, bursts; there was no provision for fully automatic fire. In 1983, the Marine Corps adopted the M16A1E1 as the M16A2, followed by the Army three years later.

By the 1990s, the use of optical sights was becoming more prevalent on U.S. service arms. While such sights could be mounted to the M16’s carry handle, a lower mount closer to the bore is optimal. To better utilize optics, the M16 family’s fixed carry handle was replaced by a removable handle that, when taken off, revealed a “flat-top” receiver with a Mil-Standard 1913 Picatinny rail. The modified M16A2 became the M16A4 (the M16A3 was a flat-top receiver A2 with full-automatic capability). In July 1997, the A4 was officially adopted by the Army, followed by the Marines in 2002.

While the M16 continued to be refined to meet the needs of the modern battlefield, the seeds of the demise of the 20"-barreled rifle had been sown during the Vietnam War. Immediately after the M16 was adopted, there was a demand for a shorter carbine version. After experimenting with several designs, the XM177E1 was introduced in late 1967 with a 10" barrel capped with a 4.5" “moderator” and a stock that telescoped along the carbine’s receiver extension for a package that weighed slightly more than 5 lbs. and collapsed down to 28" (February 2019, p. 44).

Colt’s M16 carbine program continued after the Vietnam War and resulted in the Model 653, an A1-style carbine that used a 14.5" barrel, which gave it the same overall length as the XM177E1 with its moderator. After the adoption of the M16A2, the Army sought an updated carbine that would have many of the features of the A2 rifle. Colt started developing the XM4. It was adopted in 1994 as the “Carbine, M4.”

The M16 and its 20" barrel began to show its limitations in the military actions that followed the 9/11 attacks. Troops increasingly wore body armor, and the M16A4’s fixed stock could make the rifle’s length of pull too long. The M16’s overall length made the rifle unwieldy when traveling in Humvees and MRAPs and for combat operations in confined urban spaces. By the early 2000s, the Army was replacing its M16 rifles with the M4 carbine for frontline service. The proud riflemen of the Marine Corps held out the longest. It wasn’t until 2015 that they announced they would replace their M16s with M4s. While the U.S. still fields the M16, the M4 has become the new king of the battlefield.

FN America celebrates the company’s role as a supplier of firearms to the U.S. armed forces with its Military Collector series, which offers M4-, M249- and M16-style rifles. For the Military Collector M16, FN takes its standard FN 15 20" rifle (now discontinued) and adds a Knight’s Armament M5 Rail Adapter System (RAS). The RAS, a two-piece, non-free- floating design with four full-length M1913 rails, allows the bottom rail section to be removed so that a grenade launcher can be attached. The Military Collector edition also substitutes the military-issued MaTech folding back-up iron sight for the standard carry handle.

FN takes the details further, down to its nonfunctioning “AUTO” marking on the receiver (though technically such a marking would be found on the full-automatic M16A3 and not the M16A4, which would have a “BURST” selector position) and its Unique Identification (UID) label on the magazine well. The resulting rifle is a near-perfect visual replica of the M16A4.

On The Range

For accuracy testing, I evaluated both rifles “as issued.” For the BRN-601 this meant using its iron sights (though the 601’s fixed carry handle has provisions for mounting optics). The A1-style rear sight has an “L” flip with two apertures. Both apertures are the same size, with the standard aperture designed for 0-300 meters and the “L” marked aperture for 300-400 meters. Though designed to be adjusted with the aid of a bullet tip, those zeroing an A1-sight-equipped rifle will find the task much easier if they use a sight adjustment tool.

For the FN 15, I mounted a Trijicon TA31RCO-A4CP 4X 32 mm Advanced Combat Optical Gunsight. The ACOG is the sight the Marine Corps issues with its M16A4 and features an illuminated reticle system, with a red chevron as its aiming point, that combines fiber optics with tritium for battery-free operation. Its built-in bullet drop compensator is calibrated for the 62-gr. M855 cartridge fired from a 20" barrel. With its forged aluminum housing, the ACOG and its mount add a pound to the rifle.

For those who have used a military M16, both of the rifles’ triggers will be familiar. Each are “service-grade” single-stage units. The 601’s trigger broke at 5 lbs., 8 ozs., and the FN’s at slightly more than 7 lbs.—within the military’s acceptable range of a 5-lb., 8-oz. to 9-lb. pull. Reliability was also “mil-spec” in that I experienced no malfunctions with either rifle throughout testing.

The Brownells and FN each feature chrome-lined bores. While chrome lining sacrifices some accuracy for durability, both rifles still exhibited service-grade accuracy. The 601’s 1:12" twist only gave satisfactory results with 55-gr. bullets. This is not an issue, as plenty of excellent practice, match and defensive rounds are available with this bullet weight. The FN’s 1:7" twist barrel handled a wide range of bullet weights equally well.

Stepping away from the bench for off-hand shooting, both rifles come into their own. For those whose AR experience extends only to fully accessorized M4-style carbines, the BRN-601 is a revelation. Adding optics, lasers and lights can push the weight of an M4 upward of 10 lbs., eclipsing its original purpose as a compact and handy rifle. In contrast, the 601 is a lesson in simplicity, an AR-15 stripped to its most basic. It carries, handles and points more like an M1 carbine than a modern AR.

Those who have shot heavy-barreled ARs will be pleasantly surprised when handling the FN 15. Its 20" A2-profile barrel, mated with its fixed stock, result in a perfect off-hand balance. While the FN’s refinement over the 601 is obvious, it pays a price in complexity, weight and cost.

In these two rifles the technical and historic trajectory of the M16 is clearly traced, from an innovative and revolutionary lightweight arm whose flaws were revealed when it was pressed into service as a front-line battle rifle, to a design that has reached perfection at the cost of losing sight of its original intent. The Brownells Model BRN-601 and FN 15 Military Collector M16 give you the choice of either extreme.

While the M4-style AR has become America’s gun, there are still plenty of reasons to choose an AR-15 with a 20" barrel. Maybe you want the added velocity that those few extra inches can provide. Maybe you want to experience and honor the history of the M16’s decades of service for the U.S. military. Maybe you want the benefits of the reliability and durability of the original AR-15 design. Or maybe you just want your AR-15 to be a rifle.

Colt’s SP1: The Original Civilian AR-15

The history of the civilian AR-15 closely parallels its military counterpart. In 1959, Colt bought the manufacturing rights to ArmaLite’s AR-15 and continued to refine the rifle. The design was soon adopted by the U.S. military as the M16 in 1963. At the same time, Colt started manufacturing a semi-automatic-only, civilian version of the M16. It called it the “AR-15 Sporter,” also known as the “SP1”.

When introduced, the SP1 retailed for $189.50 (at the time the U.S. military was paying $125 for its M16s in bulk). American shooters now had their own version of “the black rifle.” For 20 years, the SP1 would be the only AR-15 in the civilian world. Colt marketed the rifle as a do-all firearm, in the same way it had sold the design to the U.S. military. One of the earliest Colt ads called the SP1 “the superb hunting partner” that was ready for “adventure” and perfect for the “hunter, camper or collector.”

Early SP1s closely mimicked the Colt 601 version of the M16, with a three-prong “duckbill” flash hider, solid stock, fenceless “slabside” lower receiver and upper receiver sans forward assist. The rifle was modified to have a special large-diameter pivot pin that screwed together (the slabside lower lacked a housing for the pivot pin detent and spring) that prevented the SP1 components from having compatibility with M16 upper and lower receivers. This design feature would define Colt AR-15s into the early 1990s.

By the early 1970s, the SP1 got some of the upgrades of the M16A1, including a chrome-lined barrel, bird-cage flash hider and hollow buttstock with trapdoor, but it was never given the A1’s forward assist. In 1977, a carbine version of the SP1 was introduced that mated an NFA-legal 16"-barreled upper receiver to a lower receiver that used the two-position receiver extension and aluminum collapsible stock of the XM177 carbine.

The SP1 also introduced the AR-15 to the American law enforcement market. “Arm your men with confidence” instructed a Colt law enforcement ad, which features a tie-wearing, revolver-carrying trooper holding an SP1 in an early thumb-over-bore assault position. The ad called the rifle “Colt’s answer to the law enforcement agencies’ demands for a semi-automatic version of the M16 automatic rifle purchased by the United States Armed Forces.” The SP1 replaced pump shotguns and M1 carbines in law enforcement armories around the country. It answered the need for a modern rifle as police departments were developing their first tactical teams and the SP1 dominated the hat-on-backwards, jumping-out-of-a-bread-truck SWAT team era.

In 1977, Stoner’s patents expired and other companies started making AR-15-style components and rifles. Colt now had competition. As the U.S. military modernized its M16 with the introduction of the M16A2, Colt updated its Sporters. Production of the SP1 ended in 1985. In 1984, Colt had introduced its AR-15A2 “Sporter II” line. Curiously, early AR-15A2s used the barrel profile and furniture of the M16A2 combined with the SP1’s slabside lower receiver and an A1-style upper receiver with no forward assist.

It was a trend that would mark Colt’s civilian AR-15s into the mid-1990s. Rifles would be a mix of SP1, A1 and A2 features, often changing during a model’s production run. Many AR-15A2-era Colts still used an SP1-style slabside lower. Upper receivers were a mishmash of no-forward assist, A1 or A2 forward assist configurations that sometimes had a case deflector and sometimes didn’t. Rear sights could be A1 or A2 style.

Post-1989, Colt’s rifles became the company’s “Sporter Target” line. The name “AR-15” was dropped from the rifle’s receiver, as was the bayonet lug from the front sight base. By the time their production was ended by the 1994 ban, Colt Sporter Target rifles had been standardized with A2-type lowers. “Match Target” Colt AR-15s, lacking both flash hiders and bayonet lugs, would carry the brand through the next decade.

All the while, used SP1s could be had at a reasonable price. They were old-school in a time of tactical “wonderguns,” when most shooters wanted the latest and greatest innovations in AR-15 design. The SP1 was one of the only choices for those looking for a vintage-style rifle and who didn’t want to spend the time scouring gunshows for the surplus parts needed to build a period-correct example. Then came the AR boom. First it was mid-lengths, then SPRs, on to AR pistols and .300 Blackout, and finally … retro rifles. The SP1, the original retro, was once again relevant.

In the modern AR-15 market more AR-style rifles are probably built in a month than the total number of SP1s in existence. During the rifle’s production history, parts and features were in a constant flux that mirrored the military’s refining of its M16, leaving a diverse and fertile field for the SP1 collector. In the current market, SP1s consistently bring prices in the four-digit range, with pristine early variants pushing past the $3,000 mark. What was old is new again, and America has once again “discovered” its original AR-15, the SP1.