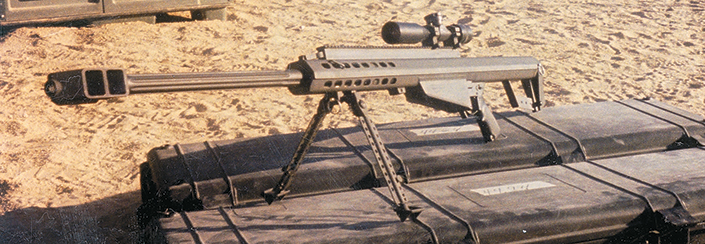

This camouflaged M82A1 was used by the U.S. Marines during Operation Desert Storm. The rifle is currently on display at the National Firearms Museum.

This article was first published in American Rifleman, April 2004

Even a casual survey of small arms design during the past two centuries will reveal that many of the major milestones, including the development of fixed metallic cartridges and repeating firearms, came from designers and engineers working on their own initiative outside the control or sponsorship of governments or military arsenals. On the whole, small arms technology has generally passed from civilian to military hands, rather than vice versa. A current case in point is the semi-automatic M82A1 or “Barrett Light Fifty” rifle chambered for the .50 Browning Machine Gun (.50 BMG) cartridge.

Ronnie Barrett, the founder of Barrett Firearms, as well as the designer and individual patent holder of the M82 “Barrett Light Fifty,” is among the many enthusiasts who enjoy the challenge of shooting very long range targets with guns chambered for .50 BMG. Barrett came to the sport during its long infancy at a time when there were no commercially manufactured guns chambered in .50 BMG. Barrett and other pioneers found there were only two options open to them: They could re-barrel surplus anti-tank rifles, such as the .55-cal. British Boys or German Panzerbuchse 39, to .50 BMG or go to the expense and trouble of building a custom rifle.

Whichever route those early .50 BMG pioneers chose, one common problem remained—recoil. Even though most of the guns weighed more than 20 lbs., that was not enough to tame a cartridge that fired 650- to 750-gr. projectiles at velocities that topped 2700 f.p.s. Some of the surplus conversions as well as many of the early custom guns were prone to harsh recoil that ranged from merely unpleasant to downright dangerous.

Ronnie Barrett’s semi-automatic M82 “Light Fifty” approached the problem of excessive recoil from two angles. First, the gun operates on the short-recoil principle. The recoiling barrel and bolt assembly acting against spring and buffer assemblies replace the sharp recoil impact of a single-shot or bolt-action design with a longer-acting, slower recoil force. Secondly, he fit the gun with a muzzle brake that was highly effective. Barrett’s muzzle brake redirects high-velocity gas and is claimed to lower recoil by almost 70 percent. The net effect is a .50 BMG rifle with perceived recoil comparable to that of a 12-ga. shotgun.

In detail, the M82 measures almost five feet in length and weighs nearly 30 lbs. The .50 BMG cartridges are fed from a detachable, double-column, 10-round steel magazine. Although bull-pup designs have long been popular in .50 BMG circles, the Barrett M82’s components are arranged conventionally with the magazine in front of the trigger guard.

Removing the mid- and rear-lock retaining pins and retracting the bolt out of battery allows the user to remove the upper receiver from the lower receiver to reveal the inner workings of the rifle. The upper and lower receivers consist of heavy-gauge sheet steel. Each half is bent into the shape of a “U” with its vertical legs splayed outward so that when the two halves are assembled, they give the receiver a hexagonal contour. As one pulls upward on the rear of the upper receiver it pivots at the front until both halves separate.

A heavy steel locking collar retains the barrel in the upper receiver. The locking collar will stop the barrel’s rearward movement after about 2" of travel. One can gauge the limits of the barrel’s travel after firing by pushing on the muzzle to the rear. Two coiled barrel return springs and a floating synthetic cylindrical buffer that surrounds the barrel rest in the space between the locking collar and front of the receiver. The barrel return springs are pinned to both the barrel locking collar and to the front of the receiver. Removing the locking collar from its recess allows the barrel to be withdrawn inside the upper receiver for more compact storage and shipping. The fluted barrel is topped off by a double-baffle muzzle brake, which is clamped to the muzzle by two Torx-head machine screws.

Tilting the lower receiver forward frees the bolt assembly from its guide rails in the lower receiver. The massive bolt features three locking lugs that surround a bolt face recessed for better cartridge support. The sliding-plate extractor is at the 9 o’clock position between the locking lugs. Ejection is by means of a spring-loaded plunger on the bolt face. Inside the bolt assembly is a coil spring that helps ensure the massive bolt head rotates fully into battery.

The Barrett’s synthetic buffer and steel recoil spring are retained in their recess at the rear of the lower receiver by a stud projecting from the inside wall. There is a groove in the side of the buffer, which, if aligned with the stud on the receiver, allows the buffer and recoil spring to be removed from the lower receiver.

External features of the Barrett include a thick rubber recoil pad with a great deal of “give” to help absorb the recoil energy of the .50 BMG round. The gun’s bipod legs look similar to those used on the M60 machine gun, but are significantly different in that they can be folded to the front as well as to the rear. Similarly, the contour of the pistol grip resembles that of an M16A2, but the Barrett’s grip is different in that it is raked more heavily to the rear to help the shooter better manage recoil. In the trigger well, the hammer, trigger and sear are arranged in a layout similar to that of the AR-15 rifle. Although they work in a similar fashion, those components are much larger and heavier and are, therefore, not interchangeable.

A Picatinny rail runs the length of the upper receiver to maximize scope-mounting options. The 30 mm steel scope rings are adjustable for elevation and windage, a feature important because many scopes can run out of vertical adjustment when shooting .50 BMG competition, where distances frequently exceed 1,500 yds. For emergencies, back-up iron sights consisting of a front post and rear aperture that fold down out of the way when not in use are included on the Barrett as well.

Barrett Firearms offered its first M82 Light Fiftys for commercial sale in 1983. The M82’s low recoil and well-thought-out features made for brisk sales, even though it was such a relatively expensive and specialized firearm. Military interest in the innovative M82 was, however, cold because the military could not envision a mission for the gun.

Additionally, there was not a great deal of success in the history of comparable rifles in military hands. Many bolt-action and single-shot .50-cal. rifles were produced between the World Wars as anti-tank rifles, but their range was limited and, as mentioned earlier, their recoil was vicious. Later they were replaced by recoilless anti-tank rockets like the bazooka and panzerfaust, which proved much more effective.

The Barrett was, however, something altogether different from those early guns. Although it was relatively heavy, especially when compared to modern small arms, it was also accurate at long range as well as sturdy and reliable. Barrett would come into its own in the hands of the Norwegian army, which bought the M82 as a tool for ordnance disposal. Norwegian peacekeeping troops who specialized in the disposal of unexploded ordnance (EOD) and landmines saw an advantage in shooting mines from a distance with the M82. This reduced the risk to their EOD personnel because there was no longer any need to approach or handle the mines after they were located and identified. The ordnance could be shot from farther away and armor-piercing .50 BMG bullets consistently detonated even thick-walled projectiles, such as 155 mm howitzer shells and bombs dropped from aircraft.

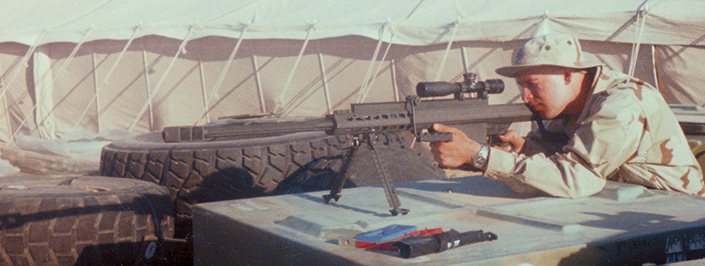

Desert Storm proved to be the Barrett’s first use in combat, when 100 M82A1s were supplied to the U.S. Marine Corps, which had requested them with a letter of special urgency. Marine special operations troops planned to use the Barrett rifles to destroy hard targets, such as radar sites, bunkers and light armored vehicles. For special operations troops or other lightly armed soldiers, carrying a Barrett and 100 rounds of .50 BMG ammunition was far more practical than lugging around two dozen LAW or AT-4 anti-tank rockets. Additionally, the Barrett also provided a range advantage over LAWs and AT-4s that are, at most, accurate to only 400 or 600 yds., which is well within the range of enemy small arms.

In the following decade, the Marines bought 300 more Barretts before the Army picked it up as the XM107 in late 2001. The Army’s original specification was geared toward a long-range sniper rifle, so a more accurate bolt-action design was a requirement. Barrett Firearms submitted its bolt-action rifle for evaluation, but tests showed that the troops preferred the rate of fire provided by a semi-automatic, so Barrett re-submitted the M82A1, which the Army provisionally designated the XM107.

Two years later, in August 2003, the gun was officially adopted as the U.S. M107, and the U.S. military ordered 2,142 guns to be delivered over the course of the following 45 months. Additionally, the U.S. Military has the option to buy another 1,100 rifles in the subsequent two years.

Barrett M107s are delivered in a “deployment package” consisting of two ABS Pelican cases containing an M107 gun, six 10-round magazines, a Leupold Vari-X IV 4.5-14X scope and a combination drag bag/shooting mat in addition to other accessories, such as a sling and muzzle cover. The M107 is now standard equipment across the services for EOD personnel and, of course, the Marines, who were the first U.S. military service to adopt the rifle. The Marines still use a nearly identical gun they have designated the M82A3. Differences include a heavier barrel bumper and a taller sight base under the Picatinney rail. The M82A3 is fitted with a fixed 10X Unertl scope with adjustable parallax, and its back-up iron sights consist of a flip-up front post with no rear aperture. The scale of the current contract is quite large, and Barrett made its first delivery to fulfill the contract in December, 2003. I recently spoke to Barrett representative Bob Gates, who emphasized, “The employees of Barrett are working around the clock to get the M107 in the hands of our troops. We know they are desperately needed.”

In the current conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan the Barrett would seem to have a lot of utility. The enemy is known to use trucks as carriers for suicide bombs or as “technicals” that fire heavy machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades or improvised mortars on the move. Responding with machine guns or anti-tank rockets carries the risk of collateral damage; the former because of their dispersion and the latter due to their limited range and heavy shaped-charge explosives. The .50 BMG round fired by a Barrett, on the other hand, has enough power to stop a truck, but is far more precise than a machine gun and not necessarily explosive like an anti-tank rocket or missile.

Indeed the U.S. Army’s own “Lessons Learned” report from Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) states: “The Barrett .50-cal. Sniper Rifle may have been the most useful piece of equipment for the urban fight—especially for our light fighters. The XM107 was used to engage both vehicular and personnel targets out to 1,400 meters. Soldiers not only appreciated the range and accuracy but also the target effect. Leaders and scouts viewed the effect of the .50-cal. round as a combat multiplier due to the psychological impact on other combatants that viewed the destruction of the target … . The soldiers that employed the XM107 and their leaders had nothing but praise for the accuracy, target effect and tactical advantage provided by this weapon.”

Indeed the U.S. Army’s own “Lessons Learned” report from Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) states: “The Barrett .50-cal. Sniper Rifle may have been the most useful piece of equipment for the urban fight—especially for our light fighters. The XM107 was used to engage both vehicular and personnel targets out to 1,400 meters. Soldiers not only appreciated the range and accuracy but also the target effect. Leaders and scouts viewed the effect of the .50-cal. round as a combat multiplier due to the psychological impact on other combatants that viewed the destruction of the target … . The soldiers that employed the XM107 and their leaders had nothing but praise for the accuracy, target effect and tactical advantage provided by this weapon.”

To help give some life to these official reports I was lucky enough to talk to Eric Poole, a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) who works in NRA’s Competitions Division. Eric was a Sergeant in B Co., 4th Light Armored Reconnaissance (LAR) Battalion of the Marine Corps Reserves, which operated as E Co. of the active duty 3rd LAR Battalion. for the duration of its deployment to Kuwait and Iraq for OIF. Eric was assigned to be a Designated Marksman for the company by the executive officer (XO) Major Dave Duhamel. As the company armorer, Eric already knew how the gun worked. He told me that the training supplied by his battalion proved to be vital, “Shortly before the invasion of Iraq my unit moved to a battlefield from the first Gulf War that was used as an improvised range to sight-in and practice shooting. We shot at steel plates and wrecked vehicles. Some troops from other battalions were less prepared and found that their shots were all over the place because they hadn’t been taught correctly. They were not even aware of the necessity of zeroing the scopes mounted to the Barrett rifles.”

Two Barretts were usually assigned to each LAR rifle company and two more were in the hands of the scout-snipers of the battalion’s Surveillance and Target Acquisition (STA) platoon. The Company XO is generally responsible for the employment of Barrett rifles in the line company. Eric told me, “We usually set up on high ground or buildings within the company’s perimeter and provided security below. The Barrett was a big help in maintaining perimeter security, because even though the 25 mm chain guns of the Light Attack Vehicles are more powerful, you cannot run their turrets all the time because that will drain the batteries and the only way to recharge them is to run the engine. We also used the Barrett to mark targets for LAV gunners who had trouble picking them up in the confusion of an ambush or raid. The thermal sights of the LAV could detect targets a long way away, but the image they show often has poor resolution. I could help them better identify enemy troops because of the clarity of my scope. In southern Iraq, the desert provided long lines of sight, but the intense heat created a great deal of mirage that made range estimation with the mil-dot reticle more difficult. Once you had your range, the MK211 ‘Raufoss’ High Explosive Incendiary Armor Piercing (HEIAP) rounds developed by the Norwegians proved to be very accurate. We were issued them for use with the Barrett instead of standard M33 ball, which was not as accurate but worked well enough and could be used in a pinch. We did not use Sabot Light Armor Piercing (SLAP) because the high pressure and velocity of the saboted .308 projectiles would ruin a barrel almost immediately.”

Two Barretts were usually assigned to each LAR rifle company and two more were in the hands of the scout-snipers of the battalion’s Surveillance and Target Acquisition (STA) platoon. The Company XO is generally responsible for the employment of Barrett rifles in the line company. Eric told me, “We usually set up on high ground or buildings within the company’s perimeter and provided security below. The Barrett was a big help in maintaining perimeter security, because even though the 25 mm chain guns of the Light Attack Vehicles are more powerful, you cannot run their turrets all the time because that will drain the batteries and the only way to recharge them is to run the engine. We also used the Barrett to mark targets for LAV gunners who had trouble picking them up in the confusion of an ambush or raid. The thermal sights of the LAV could detect targets a long way away, but the image they show often has poor resolution. I could help them better identify enemy troops because of the clarity of my scope. In southern Iraq, the desert provided long lines of sight, but the intense heat created a great deal of mirage that made range estimation with the mil-dot reticle more difficult. Once you had your range, the MK211 ‘Raufoss’ High Explosive Incendiary Armor Piercing (HEIAP) rounds developed by the Norwegians proved to be very accurate. We were issued them for use with the Barrett instead of standard M33 ball, which was not as accurate but worked well enough and could be used in a pinch. We did not use Sabot Light Armor Piercing (SLAP) because the high pressure and velocity of the saboted .308 projectiles would ruin a barrel almost immediately.”

Eric also put me in touch with his friend, Sgt. Khanh Nguyen, a qualified Scout-Sniper with his battalion’s STA platoon. He was trained with the Barrett and other sniper systems in Scout-Sniper school. During OIF, Sgt. Nguyen crewed an LAV-AT, an anti-tank version that mounts a TOW anti-tank missile. Sgt. Nguyen told me, “Since there was no chain gun I kept the M82A3 Barrett on the roof of the LAV and often shot it from there. I thought it was great for destroying technicals and light armored vehicles like BMPs. They could be engaged out to 2,000 yds. or more, but with the current ammo it really is not accurate enough for sniping. The M40A1 is still a better choice for that role.”

Although the military was slow to warm to the Barrett, the troops are clearly sold on it. But it would never have reached their hands without its prior commercial success due to budget cuts and military narrow-mindedness that can make chasing military and government contracts a feast or famine proposition for gun and ammunition manufacturers. The example of the Barrett Light Fifty is more evidence showing how a healthy commercial firearms market improves our military readiness and makes our soldiers safer.

Shooting The M82A1

Barrett Firearms recently supplied us with a commercial M82A1 for testing. The rifle came in an olive drab Pelican case with two 10-round magazines. We had the opportunity to shoot it—from a machine rest with an equivalent of M33 FMJ ball loaded by IMI—under the direction of S/Sgt. Aman, an armorer with the USMC’s Weapons Training Battalion at Quantico. Our results from shooting at targets 300 yds. away are shown in the accompanying table. The accuracy results are not as good as those of bolt-action .50 BMGs we have tested in the past, including Barrett’s M99, but those were shot with match-grade cartridges loaded with hollow-point bullets. The results, however, are better than the military standard of 4 m.o.a.

Later, at our own test range, we shot the Barrett M82A1 off the bench. The gun was well behaved, and it did not abrade the cheek or the firing hand. The recoil pad had a lot of give to absorb the force of the recoil and it was slightly tacky like neoprene, so it did not slip out of the shoulder’s pocket. The often-cited comparison to shooting a 12-ga. shotgun is quite accurate as far as recoil goes, but when the trigger is squeezed the noise and shock wave coming back from the muzzle reminds the shooter of the tremendous energy going downrange. The blast from the muzzle brake testifies to its effectiveness, and after firing more than 70 rounds it did not work loose or otherwise fail. Observers should stand directly behind the shooter and the firing line should be free of other shooters because the noise and blast is directed at roughly 45 degree angles back toward the firing line. To paraphrase what film character Ferris Bueller said about a Ferarri, if you have the means, shooting the M82A1 is an experience not be missed.

—Glenn M. Gilbert