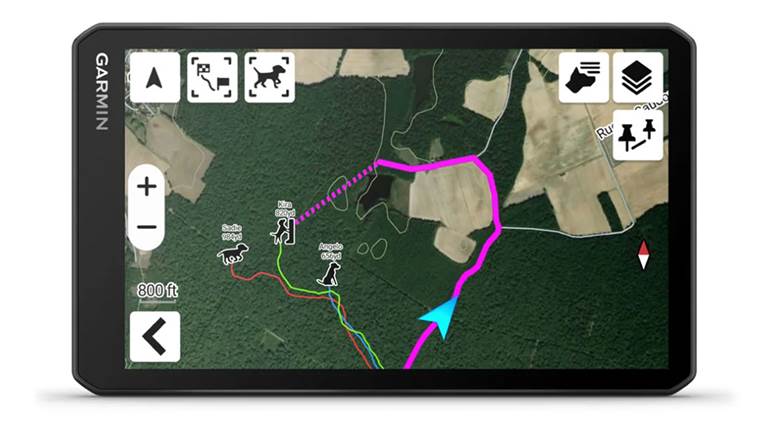

Garate, Anitua y Cía sold a small number of .455-cal. revolvers to the British government during World War I (l.). This damascened example, an OP No. 1 Mark 1 prepared by F.A. Larrañaga, features the “Order of the Thistle” on the barrel’s left side, a symbol that was also used by the Scots Guards. Above the revolver is a burnishing tool; a selection of damascening punches and an engraver’s mallet are grouped to the left.

Although beauty is in the eye of the beholder, anyone who likes guns can probably appreciate fancy-looking ones. This is especially true for anyone who has purchased “for investment.” We all know to buy the best we can afford and, for the lucky few, buying the best usually means a factory-engraved gun—particularly those signed by a notable artisan. If a Colt, find an example with Nimschke engraving; if a Winchester, look for Ulrich’s signature. Then there is a Felix Funken- or Angelo Bee-engraved Browning, an Enoch Tue-engraved Savage, the list goes on … .

But what about those looking for something really, really special—a truly unique firearm whose presentation would totally eclipse the work of any of the aforementioned artisans? If you have ever entertained such a purchase, would you consider a gold damascened gun? Never heard of it? It’s not surprising; the vast majority of gun owners are totally unfamiliar with this process.

Gold damascening was introduced in the 13th century, with most of the early decoration applied to armor and firearms. Time-intensive to apply and expensive to acquire, it was largely an affectation for nobility. Yet the art form proved popular in France during the 1600s and then in Holland and Belgium in the early 1800s.

The Damascening Process

Though popularly described as “the art of inlaying different metals into one another,” the process is really quite different. In fact, seldom is there any inlaying, rather, there is a reliance on much more superficial adherence (See the illustrations under “A Brief Overview Of Damascening” below).

Traditionally, the bare metal is scored/scratched in several directions to create a field of microscopic barbs. Super-thin gold, either foil or thread, is laid out in a pre-ordained pattern, then pressed onto the surface. The barbs pierce the gold, then bend during hammered application, securing the gold in place. The work is then blued to darken the background. The final step, known in Spanish as the “repasado,” is to go over the work, detailing the gold forms with a variety of punches while matting or burnishing the background. A thicker application of gold might require some inlaid undercutting, but that would be the exception, not the rule. Pure, yellow, 24-carat gold is the classic material. Red and green gold is used less frequently; silver and even platinum may be used for highlighting.

PlÁcido Zuloaga, Father of Modern Damascening

A native of Eibar, Plácido Zuloaga (1834-1910), is generally credited with popularizing the damascening renaissance in Spain. After he and his father, Eusebio, won a Parisian art exhibition in 1855, Plácido went on to transform his family’s gunmaking factory into a firm creating objets d’art, eventually winning 36 gold medals in international art competitions. Examples of his work were purchased by Spain’s King Alfonso XII for presentation to the king of Portugal and the king of Bavaria. Other items bought by English textile magnate Alfred Morrison received worldwide recognition. Universally considered the “Father of Damascening,” Zuloaga’s artwork, especially his signed pieces, are the “holy grail” items of this genre.

As one might expect, Zuloaga’s successes attracted a number of apprentices. Some made small, easy-to-sell items to pay the overhead. Others collaborated in effecting major commissions. By 1890, Zuloaga had trained more than 200 artisans. Most left his firm to set up independently and, in the process, broadly commercialized the industry by decorating brooches, bracelets, belt buckles, tie pins, cane heads and other related objects. Eventually, there came to be two centers for damascening, one in Eibar (Renaissance), the other farther south, in Toledo (Arabesque). For the most part, artwork originating from Eibar tended to feature representations of living forms, such as dragons, gargoyles, dogs, songbirds, egrets, cherubs, scrolling vines and flowers. Artisans from Toledo, heavily influenced by the Moorish culture, favored exacting geometric forms, architectural perspectives (especially scenes from the Alhambra Palace in Granada) and the Arabic inscription/Nasrid motto that translates to “There is no victor but God.”

Although damascened jewelry became popular and plentiful, particularly in the early 1900s, the decoration of firearms remained very costly. Their large, complicated surfaces required a lot of time to lay out the pattern and then execute the work. In the 1930s, most damascened guns were priced about four times more than a blued gun. Over time, as wages increased, the gap widened. By the 1950s, damascened guns were nearly six times the price of a standard gun, more so if ordered with damascened stocks.

To say that only “a few” damascened guns were completed would be an understatement. As a very rough guide, looking at Astra’s and Star’s production, only one damascened firearm was completed per 10,000 standard guns! Smaller pistols that cost less were sold more frequently, while larger guns were sold less frequently.

To put their rarity into context, Louis D. Nimschke engraved an estimated 5,000 firearms between 1850-1904, divided among Colt, Winchester and a few lesser-known makers. In contrast, during Astra’s nearly 100 years as a firearm manufacturer, the company made just over one million guns—yet only about 100 were gold damascened!

As so few were completed, it made no sense for a gunmaking firm to keep a dedicated damascene artist on its payroll. It was far more practical to farm the work out. Given the limited selection of nearby artisans and the cross-talk between companies, it should come as no surprise that several artists worked with equanimity for Astra, Star and Llama. Some of the better-known artists include: Adolfo Santos of Eibar, who decorated many of Astra’s Model 900-series pistols from the early 1930s and favored scenes from the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain; Miguel F. Zubimendi, one of the best artists from the Basque provinces, who was most active from the 1950s to 1970s and preferred elevated figurines, extensive scrollwork and borders made of three fences—one of foil, two of gold wire; Lucas Alberdi, who worked on quite a few Astra, Llama and Star pistols from the late 1940s to 1960s (although his “signature” was a dragon within a heavily bordered shield, he also favored unusual borders, particularly paving stone, or meandros, highlighting); Jesús Pardo, who is widely renowned for his work in Toledo and who used finely detailed Arabic patterns with shielded inscriptions, silver highlighting and extraordinarily precise geometry to great effect; and Maria Jesús Berasaluce Rodriguez, of Ermua, who did virtually all the damascening work for all three firms from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s.

While most damascening was completed without a signature, a comparison of factory records against the known work of some of the more prolific artisans allows many of the embellished guns to be properly credited. Just as telling is a comparison of their “signature” motifs and styles.

Although most companies had a few damascened firearms for display in their front office or trade shows, the guns were too expensive and infrequently sold to speculatively inventory. The vast majority were special ordered for political presentations, military awards or at the request of wealthy customers. From the Spanish perspective, a little “New York” engraving with a few gold inlays wasn’t good enough. These guns needed to be spectacular, the best of the best, for maximum visual impact. As flagship firearms, they were customarily fitted with special stocks, often personalized, with presentation cases.

Most guns from the early 1900s had mother-of-pearl (MOP) panels. By the late 1920s, the MOP was replaced, first with less-expensive celluloid, and later with plastic. Depending on the customer’s wishes, many panels were recessed for special-order escutcheons—some with intertwined initials, others bearing the seal of the recipient’s country.

What about accessories? As one might expect, there was a wide variety of presentation cases, sometimes by a single manufacturer. Astra’s most elegant was leather-bound with gold-gilt trim, lined in silk and velvet, with paired, spring-loaded locks. For a brief period, Star offered a similar case but with cow hair attached to the exterior. A far more luxurious case was made of hand-tooled leather with a suede interior. On the other side of the spectrum were the paper-covered cases, sold by a variety of lesser manufacturers, secured with flimsy hinged clasps.

Assessing Quality

Although every artist likes to promote his or her work as the best, the most lifelike, the most intriguing, the most-cutting edge, etc., we know better. That is why we have talent shows, art exhibits and competitive displays. All artists aren’t created equal, so how do you tell the difference? A few guidelines can be used to assess artistic talent:

Poor (1.): The least-demanding work uses large, repetitive patterns of foil with minimal detailing. Borders are non-existent or coarse and fraught with overruns and irregularity. In some cases, the gold was so poorly applied that it peels with the slightest provocation.

Intermediate (2.): As the quality improves, more attention is paid to the bordering, the detailing of the figures and the surrounding scroll. The design should be symmetrical and aligned to the major components. Linear accents become more refined, and the animals and foliage become more lifelike.

Excellent (3.): The best-quality work involves a unique pattern with linear complexity, geometric symmetry and very fine detailing with realism as appropriate to the imaging. Lines are straight and corners are sharp. Classical Arabic inscriptions may be woven into the design that may extend to the metallic stocks, an elegant option that can add 30 to 40 percent to the surface area. One of the most complicated designs, seen on a few Star pistols, included an Aztec calendar on each stock. Thicker gold and/or multicolor gold accents may also be present.

Incomparable Art

Regardless of manufacturer, model or presentation, damascened guns are truly “show-stoppers,” whose beauty transcends the usual collecting criteria. It should come as no surprise that one of the first exhibits in the NRA’s National Firearms Museum is a gold damascened shotgun presented by Francisco Franco to Hermann Goering. A few other recipients of gold damascened firearms include: U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower; Mexican President Plutarco Calles; Francisco Franco, dictator of Spain; Manuel Noriega, dictator of Panama; Juan Perón, dictator of Argentina; Egypt’s King Farouk; and Prince Mansour of Saudi Arabia.

So why is gold damascening so overlooked by the American market? It comes down to two variables: availability (next to none) and cost (far more expensive than engraving). And most damascened guns are not Colts or Winchesters, name brands that have traditionally driven collector interest and market prices. Yet, those considerations aside, gold damascened firearms deserve far more recognition on many levels, with an emphasis on preservation for future generations.

A Brief Overview Of Damascening