Originally published in American Rifleman, March 1989.

In 1777, William Knox, Under Secretary of State in the British Colonial Office, circulated a proposal entitled, “What is Fit to be Done with America?” Knox advocated the creation of a ruling aristocracy loyal to the Crown, establishment of the Church of England throughout the colonies and an unlimited power to tax. To keep them servile, Knox offered the panacea of disarming all of the people and relying solely on a standing army:

The Militia Laws should be repealed and none suffered to be re-enacted, the Arms of all the People should be taken away, & every piece of Ordnance removed into the King’s Stores, nor should any Foundry or manufactory of Arms, Gunpowder, or Warlike Stores, be ever suffered in America, nor should any Gunpowder, Lead, Arms or Ordnance be imported into it without License: they will have but little need of such things for the future, as the King's Troops, Ships & Forts will be sufficient to protect them from any danger.1

It all began in September 1768, when rumors of an impending occupation by British troops, allegedly to suppress riots and collect taxes, inflamed Boston. A group of the freeholders led by James Otis and John Hancock met at Faneuil Hall and passed several resolutions, including the following:

WHEREAS, by an Act of Parliament, of the first of King William and Queen Mary, it is declared, that the Subjects being Protestants, may have Arms for their Defence; it is the Opinion of this town, that the said Declaration is founded in Nature, Reason and sound Policy, and is well adapted for the necessary Defence of the Community.

And Forasmuch, as by a good and wholesome Law of this Province, every listed Soldier and other Householder (except Troopers, who by law are otherwise to be provided) shall always be provided with a well fix’d Firelock, Musket, Accoutrements and Ammunition, as in said Law particularly mentioned, to the Satisfaction of the Commission officers of the Company; …VOTED, that those of the Inhabitants, who may at present be unprovided, be and hereby are requested duly to observe the said Law at this Time.2

A convention of Boston and several other towns met to consider the resolutions, and then petitioned the royal governor. When the governor rejected the petition, a patriot "A.B.C." (probably Samuel Adams) wrote:

It is reported that the Governor has said, that he has Three Things in Command from the Ministry, more grievous to the People, than any Thing hitherto made known. It is conjectured 1st, that the Inhabitants of this Province are to be disarmed. 2d. The Province to be governed by Martial Law. And 3d, that a Number of Gentlemen who have exerted themselves in the Cause of their Country, are to be seized and sent to Great-Britain.

Unhappy America! When thy Enemies are rewarded with Honors and Riches; but thy Friends punished and ruined only for asserting thy Rights, and pleading for thy Freedom.3

Two days later, the British troops landed in Boston and took over key points, including Faneuil Hall.4 However, only one report could be found that the inhabitants were being disarmed:

Advices, so late as the 10th of October, mention…

That part of the troops had been quartered in the castle and barracks, and the remainder of them in some old empty houses. That the inhabitants had been ordered to bring in their arms, which in general they had complied with; and that those in possession of any after the expiration of a notice given them, were to take the consequences.5

It is difficult to imagine much compliance with such an order, especially since such reports were not widespread with extensive protests. However, disarming the colonists was clearly being contemplated. From London, "it is said orders well soon be given to prevent the exportation of either naval or military stores, gun-powder, &c. to any part of North-America."6

In an article he signed "E.A.," Samuel Adams recalled the English Bill of Rights as explained by Sir William Blackstone:

At the revolution, the British constitution was again restor’d to its original principles, declared inn the bill of rights; which was afterwards pass'd into a law, and stands as a bulwark to the natural rights of subjects. “To vindicate these rights, says Mr. Blackstone, when actually violated or attacked, the subjects of England are entitled first to the regular administration and free course of justice in the courts of law—next to the right of petitioning the King and parliament for redress of grievances—and lastly, to the right of having and using arms for self-preservation and defence." These he calls "auxiliary subordinate rights, which serve principally as barriers to protect and maintain inviolate the three great and primary rights of personal security, personal liberty and private property": And that of having arms for their defense he tells us is “a public allowance, under due restrictions, of the natural right of resistance and self preservation, when the sanctions of society and laws are found insufficient to restrain the violence of oppression.”—How little do those persons attend to the rights of the constitution, if they know anything about them, who find fault with a late vote of this town, calling upon the inhabitants to provide themselves with arms for their defence at any time; but more especially, when they had reason to fear, there would be a necessity of the means of self preservation against the violence of oppression.7

Adams made clear that private citizens could use arms to protect themselves from military oppression. He went on to point out that the same persons who opposed the right to have arms also opposed the right to petition:

But there are some persons, who would, if possibly they could, persuade the people never to make use of their constitutional rights or terrify them from doing it. No wonder that a resolution of this town to keep arms for its own defence, should be represented as having at bottom a secret intention to oppose the landing of the King's troops: when those very persons, who gave it this colouring, had before represented the peoples petitioning their Sovereign, as proceeding from a factious and rebellious spirit.. . . .8

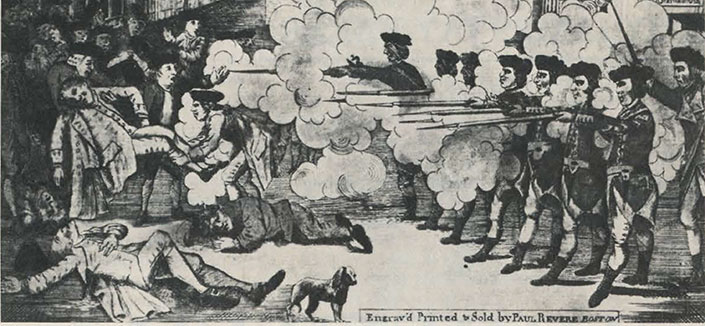

For the next half decade, the disputes escalated, from the shooting of civilians “armed” with sticks (what became known as the Boston Massacre in 1770), to the embargo on shipments of arms to America and the self-arming of the populace into militia in 1774. In September 1774, pro-British rulers in Boston proposed the disarming of the people, but the measure was voted down, perhaps because of the protest it would have evoked:

It is said, it was proposed in the Divan last Wednesday, that the inhabitants of this Town should be disarmed, and that some of the newfangled Counsellors consented thereto, but happily a majority was against it.—The report of this extraordinary measure having been put in Execution by the Soldiery was propagated through the Country, with some other exaggerated stories, and, by what we are told, if these Reports had not been contradicted, we should by this date have had 40 or 50,000 men from the Country (some of whom were on the march) appear'd for our Relief.8a

Nonetheless, by early 1775, the British began a de facto policy of disarming the colonists.

What was actually going on may be exemplified by the experience of one Thomas Ditson, who was tarred and feathered by British soldiers. In his affidavit, Ditson claimed, “I enquired of some Townsmen who had any Guns to sell; one whom I did not know, replied he had a very fine Gun to sell.”9 Since the one who offered the gun was a soldier, Ditson continued:

I asked him if he had any right to sell it, he reply'd he had, and that, the Gun was his to dispose of at any time; J then ask'd him whether he tho't the Sentry would not take it from me at the Ferry, as I had heard that some Persons had their Guns taken from them, but never tho't there was any law against trading with a Soldier; . . . I told him I would give four Dollars if there was no risque in carrying it over the Ferry; he said there was not ... I was afraid . . . that there was something not right . . . and left the Gun, and coming away he followed me and urg'd the Gun upon me. . . .10

When he finally paid money to the soldier, several other soldiers appeared and seized Ditson, whom they proceeded to tar and feather. However, instead of entrapment, the soldier swore in his affidavit that it was a case of a rebel trying to obtain arms and urging a soldier to desert. The citizen said “that he would buy more Firelocks of the Deponent, and as many as he could get any other Soldier to sell him…”11

The British were wise to the American game, and the following ammunition seizure reported from Boston also alleged that soldiers killed people along the road:

The Neck Guard seized 13,425 musket cartridges with ball, (we suppose through the information of some dirty scoundrel, of which we have now many among us) and about 300 lb. of ball, which we were carrying into the country—this was private property. —The owner applied to the General first, but he absolutely refused to deliver it.12

The Revolutionary War was sparked when militiamen exercising at Lexington refused to give up their arms. The widely published American account of April 19, 1775, began with the order shouted by a British officer:

“Disperse you Rebels—Damn you. throw down your Arms and disperse.” Upon which the Troops huzz'd, and immediately one or two Officers discharged their Pistols, which were instantaneously followed by the Firing of four or five of the Soldiers, then there seemed to be a general discharge from the whole Body.13

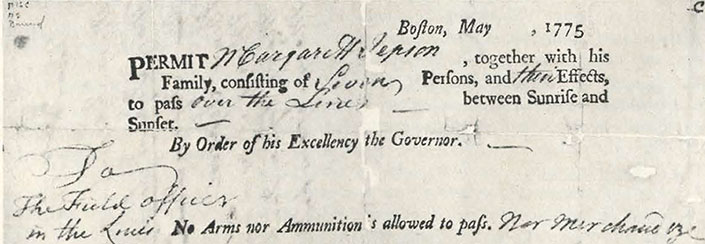

Three days later Gen. Gage represented to the Selectmen of Boston that “there was a large body of men in arms” hostilely assembled, and that the inhabitants could be injured if the soldiers attacked.14 The next day a town committee met with Gage, who promised “that upon the inhabitants in general lodging their arms in Faneuil Hall, or any other convenient place, under the care of the Selectmen, marked with the names of the respective owners, that all such inhabitants as are inclined, may depart from the town… And that the arms aforesaid at a suitable time would be return'd to the owners.”15

Bostonians proceeded to turn in 1778 muskets, 634 pistols, 973 bayonets and 38 blunderbusses.16 However, when “the inhabitants gave up their arms and ammunition—to the care of the Selectmen: the General then set a guard over the arms…"17 Gage then refused to permit the people to leave. “The same day a town meeting was to be held in Boston, when the inhabitants were determined to demand the arms they had deposited in the hands of the select men, or have liberty to leave town.”18

An anonymous patriot addressed “the perfidious, the truce-breaking Thomas Gage” as follows:

But the single breach of the capitulation with them [the people of Boston], after they had religiously fulfilled their part, must brand your name and memory with eternal infamy—the proposal came from you to the inhabitants by the medium of one of your officers, through the Selectmen, and was, that if the inhabitants would deposit their fire-arms in the hands of the Selectmen, to be returned to them after a reasonable time, you would give leave to the inhabitants to remove out of town with all their effects, without any let or molestation. The town punctually complied, and you remain an infamous monument of perfidy, for which an Arab, Wild Tartar or Savage would despise you!!!19

On June 12, Gage proclaimed martial law and offered a pardon to all who would lay down their arms except Samuel Adams and John Hancock.20 A patriot responded with a poem entitled “Tom Gage's Proclamation,” which told how the general had sent an expedition “the men of Concord to disarm” and how he afterwards reflected:

Yet e'er I draw the vengeful sword, I have thought fit to send abroad, This present gracious Proclamation, Of purpose mild the demonstration; That whoseoe'er keeps gun or pistol, I'll spoil the motion of his systole; Or, whip his breech, or cut his weason As has the measure of his Treason:-But every one that will lay down His hanger bright, and musket brown, Shall not be beat, nor bruis'd not bang'd, Much less for past offences, hang'd, But on surrendering his toledo, Go to and fro unhurt as we do:—But then I must, out of this plan, lock Both SAMUEL ADAMS and JOHN HANCOCK; For those vile traitors (like debentures) Must be truck'd up at all adventures; As any proffer of a pardon, Would only tend those rogues to harden:— But every other mother's son, The instant he destroys his gun, (For thus doth run the King's command) May, if he will, come kiss my hand.—

Meanwhile let all, and every one Who loves his life, foresake his gun:21

Gage's seizures and attempts to seize the guns, pistols, Brown Bess muskets and swords known as hangers and toledos of the individual citizens of Boston who were not even involved in the hostilities sent a message to all of the colonists that the right to keep and bear private arms was in a perilous condition. A report from London that the British were coming to seize the arms of all the colonists hit the headlines in Virginia and Maryland:

It is reported, that on the landing of the General Officers, who have sailed for America, a proclamation will be published throughout the provinces inviting the Americans to deliver up their arms by a certain stipulated day; and that such of the colonists as are afterwards proved to carry arms shall be deemed rebels, and be punished accordingly.22

The final break came when the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Causes of Taking Up Arms on July 6, 1775, which had been drafted by Thomas Jefferson and John Dickinson and which complained:

It was stipulated that the said inhabitants having deposited their arms with their own magistrates, should have liberty to depart. . . .They accordingly delivered up their arms, but in open violation of honor, in defiance of the obligations of treaties, which even savage nations esteem sacred, the governor ordered the arms deposited as aforesaid, that they might be preserved for the owners, to be seized by a body of soldiers…

Debate now turned to war, and William Knox's 1777 plan that “the Arms of all the People should be taken away” was far too late, had it ever been possible.

The above is only a small portion of newspaper extracts showing British attempts to disarm the Americans in the years 1768-1775. The grievances expressed led to the adoption of right to bear arms guarantees in the state Declarations of Rights beginning in 1776 and the federal Second Amendment in 1789.

The British resorted to every possible tactic to disarm the Americans—entrapment, false promises of “safekeeping,” banning imports, direct seizure and finally shooting persons bearing arms. As the Bicentennial of the Second Amendment approaches, the American people must make a renewed commitment to understand the historical origins of the Bill of Rights, in order to preserve their liberties.

NOTES

1. Sources Of American Independence 176 (H. Peckman ed. 1978). Emphasis added.

2. Boston Evening Post, Sept. 19, 1768, at 1, col. 3, and 2, col. 1.

3. Boston Gazette, and Country Journal, Sept. 26, 1768, at 3 cols. 1-2.

4. Boston Evening Post, Oct. 3, 1768, at 3, col. 2 (includes an account of the invasion).

5. New York Journal, Feb. 2, 1769, al 2, col. 2.

6. Boston Gazette, and Country Journal, Oct. 17, 1768, at 2, col. 3.

7. Id., Feb. 27, 1769, at 3, col. 1. Adams' authorship is confirmed in 1 H. Cushing ed., The Writings Of Samuel Adams 316 (1904).

8. Id.

8a. Massachusetts Spy, Sept. 8, 1774, at 3, col. 3.

9. Massachusetts Gazette; and Boston Weekly News-Letter, March 17, 1775, al 3, col. 1.

10. Id.

11. Id., col 2.

12. Connecticut Courant, April 3, 1775, at 2, col. 2.

13. Essex Gazette, April 25, 1775, at 3, col. 3

14. Attested copy of Proceeding between Gage and Selectmen, April 22, 1775, reprinted in Connecticut Courant, July 17, 1775, at 1, col. 3, and 4, col. 1.

15. Id. at 4, col. 2 (April 23, 1775).

16. R. Frothingham, History Of The Siege Of The Boston 95 (1903).

17. Connecticut Courant, May 8, 1775, at 3, col. 1.

18. Connecticut Journal and New-Haven Post-Boy, May 19, 1775, at 6, col. 2.

19. Connecticut Courant, June 19, 1775, at 4, col. 2.

20. Connecticut Journal and New-Haven Post-Boy, June 21r 1775, at 3, cols. 1-2.

21. Connecticut Courant, July 17, 1775, at 4, col. 1.

22. Virginia Gazette, June 24, 1775, at 1. col. 1; Maryland Gazette, July 20, 1775, at I, col. 2.

23. Connecticut Courant, July 17, 1775 at 2, col. 1. The Declaration was published in virtually every colonial newspaper.

The Continental Congress adopted a similar address on “To the People of Ireland” which complained that “the citizens petitioned the General for permission to leave the town, and he promised, on surrendering their arms, to permit them to depart with their other effects; they accordingly surrendered their arms, and the General violated his faith. . . .” Id., Aug. 21, 1775. at 1, col. 3.

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=770&height=430&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=150&height=150&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)