This feature article, "The American Lewis," appeared originally in the December 2004 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

The Lewis Machine Gun, with its large cylindrical jacket surrounding the barrel and distinctive top-mounted pan magazine, is one of the most recognizable military arms of all time. While many are aware of the Lewis gun, the story of its tenure in U.S. service is not as well known. It may be surprising to some that, although developed by a U.S. Army officer, the Lewis gained the majority of its fame in the service of other nations. Despite its proven effectiveness, the story of the American Lewis is a mixture of intra-service rivalry, petty professional jealousy and incompetence at the highest level of the U.S. Army Ordnance Department.

The genesis of the Lewis machine gun dates to 1910 when Isaac Newton Lewis, a colonel in the U.S. Army Coast Artillery, became affiliated with the Automatic Arms Company of Buffalo, N.Y. The fledgling arms firm hired Col. Lewis to develop and refine a light machine gun based on a design originally patented by an American inventor, Samuel N. McClean. Although McClean’s design had some interesting features, it was rejected by the American military after little more than a cursory glance. The Automatic Arms Company’s financial backers felt McClean’s basic design could be substantially improved and Col. Lewis was the man to tackle the job. By 1911, Lewis had developed an improved prototype, and the U.S. Army Ordnance Department agreed to test it.

The Lewis had several novel features, including a top-mounted pan magazine and a unique cooling system that utilized a radiator jacket which encased, and was slightly longer than, the barrel. When the gun was fired, the muzzle blast forced air inside the radiator and over the barrel to aid in cooling. The prototype weighed about 25 lbs., was chambered for the standard U.S. .30-cal. M1906 cartridge (.30-’06 Sprg.) and fired fully automatically at the rate of approximately 750 rounds per minute. In addition to the prototype, Lewis and his backers had four other examples fabricated for the upcoming Ordnance Department tests.

In one of the early tests, Col. Lewis arranged a demonstration to have his machine gun fired from an airplane in order to demonstrate its flexibility. On June 7, 1912, a prototype Lewis machine gun was fired by Captain Charles Chandler from a Wright Type B biplane piloted by Lt. T.D. Milling. According to contemporary reports, there were multiple hits made on the ground target. This demonstration was intended to impress the assembled Ordnance Department brass with the potential capabilities of the new arm. Unfortunately for Col. Lewis, the demonstration did not have the intended effect. Many of the senior officers present felt that firing a machine gun from an aircraft was a foolish stunt that would never be of any practical value.

The remaining demonstrations and trials fared little better, and the gun came in for a lot of criticism. Some of the complaints were valid while others fell firmly in the nit-picking category. After the tests were completed, Col. Lewis was informed that his gun would not be recommended for adoption or further development. Even though it performed relatively well in the various tests, there were several reasons, if not excuses, proffered for rejection of the design, including budgetary concerns and the fact that the machine gun served essentially the same purpose as the standardized U.S. M1909 Benet-Mercie Machine Rifle.

Reading between the lines, one cannot help but assume that at least part of the reason for the conclusions of the evaluation board was that some officers senior to Col. Lewis, especially Chief of Ordnance Gen. William Crozier, were jealous that a fellow officer might gain a measure of fame and fortune by developing such an arm.

Col. Lewis was upset enough by the turn of events to call the members of the test board “ignorant hacks.” Obviously, this was not conducive to furthering his career in the U.S. Army and, shortly afterward, Lewis submitted his retirement papers and left the service.

In early 1913 Lewis took the four prototypes to Europe, and the gun was tested by a number of foreign governments. The reception that the Lewis machine gun received overseas was in marked contrast to that encountered in the United States just a few months before. With the threat of war on the horizon, unlike the hide-bound U.S. Army, several European nations were interested in acquiring modern arms. Great Britain and Belgium were quite impressed with the Lewis, and both nations soon adopted it. Great Britain made arrangements with the Birmingham Small Arms Company (BSA) for manufacture of a .303 British version, and Belgium put the gun into production at the small arms factory in Liege. The British standardized the Lewis as the “Gun, Machine, Lewis, .303 in., Mark I.” It weighed just over 28 lbs. and employed a 47-round, top-mounted pan magazine. BSA eventually manufactured 145,397 Lewis guns during World War I. In 1915, in order to augment production, the British contracted with the Savage Arms Corporation of Utica, N.Y., for manufacture of .303 Mark I Lewis guns.

World War I broke out in Europe shortly after the Lewis production began. There were no other arms in the Allied arsenal comparable to the Lewis, and it immediately gained an enviable reputation as an effective and reliable light machine gun. To take advantage of the Lewis’ portability and firepower, the British formed infantry machine gun killer teams to eliminate German machine gun emplacements. These teams were used with notable effectiveness, due in no small measure to the lethality of the Lewis. The Germans reportedly attempted to capture, and use, as many Lewis guns as possible and gave the gun the nickname “Belgian Rattlesnake.”

The Lewis’ sterling performance was not lost on its American proponents. Some insightful individuals recognized it would only be a matter of time until America was drawn into the conflagration raging in Europe and pressed for adoption of the Lewis by the United States. Likely due in large measure to the lingering bitterness on the part of some officers, the U.S. Army Ordnance Department still considered the Lewis to be unsatisfactory. However, in 1916, the U.S. Army did agree to purchase 350 Lewis guns from Savage for use in the Mexican Punitive Expedition. Despite the non-standard .303 British caliber, the Lewis guns reportedly performed well in the Mexican campaign, especially compared to the flawed M1909 Benet-Mercie machine rifle.

The United States’ declaration of war in April 1917 resulted in an immediate need for modern infantry arm for the rapidly expanding military. The U.S. Navy ordered 6,000 Lewis guns from Savage to arm landing parties, for shipboard duty and to equip the U.S. Marine Corps. The Navy Lewis was adopted as the “Model of 1917” and chambered for the standard M1906 (.30-’06 Sprg.) cartridge. Except for minor dimensional variances due to differences between the .30-’06 and .303 cartridges and different types of bipods, the M1917 Lewis was very similar to the British version.

Shortly after the U.S. Navy contract, the U.S. Army reluctantly reconsidered the issue and placed an order for 2,500 M1917 Lewis guns from Savage. The Army, however, made it clear the guns would only be authorized for training use. The U.S. Marine Corps, on the other hand, became an enthusiastic supporter of the Lewis. A USMC Lewis Machine Gun School was organized at the Savage Arms plant to train Marine armorers.

In addition to use as an infantry arm, the Lewis machine gun became popular as aircraft armament due to its reliability and ease of changing magazines as compared to typical machine gun belts. The standard ground-model Lewis could be easily converted to aircraft use by replacing the wooden buttstock with spade grips and removing the barrel radiator. A 97-round magazine was developed for aircraft use.

When the Marines deployed to France, they carried along their trusty M1917 Lewis guns. Upon arrival, however, the Marines were dismayed when informed by the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) that they would have to relinquish their Lewis guns to be replaced by woeful French Chauchat machine rifles. The stated reason was uniformity in arms, but this explanation didn’t go over very well with the combat Marines who were extremely unhappy about being forced to exchange a familiar and reliable arm for the notably unreliable French designs. As related in the book History of the United States Marine Corps: “The Marines … turned in their trusted Lewis machine guns in exchange for French Chauchat automatic rifles and Hotchkiss machine guns, both heavy and unreliable weapons that used different ammunition from the Marines’ Springfields, and thus complicated supply problems.”

The U.S. Army Doughboys who had trained stateside with Lewis guns were also displeased with having to leave them behind, but were generally less vocal than the Marines. Some U.S. troops were temporarily assigned to British units and had the opportunity to utilize .303 Lewis guns in combat. Otherwise, in marked contrast to the British and Belgians, combat use of Lewis guns in World War I by U.S. troops was essentially non-existent. Many of the ground-model Lewis guns were diverted to the U.S. Army Air Service and converted to aircraft use.

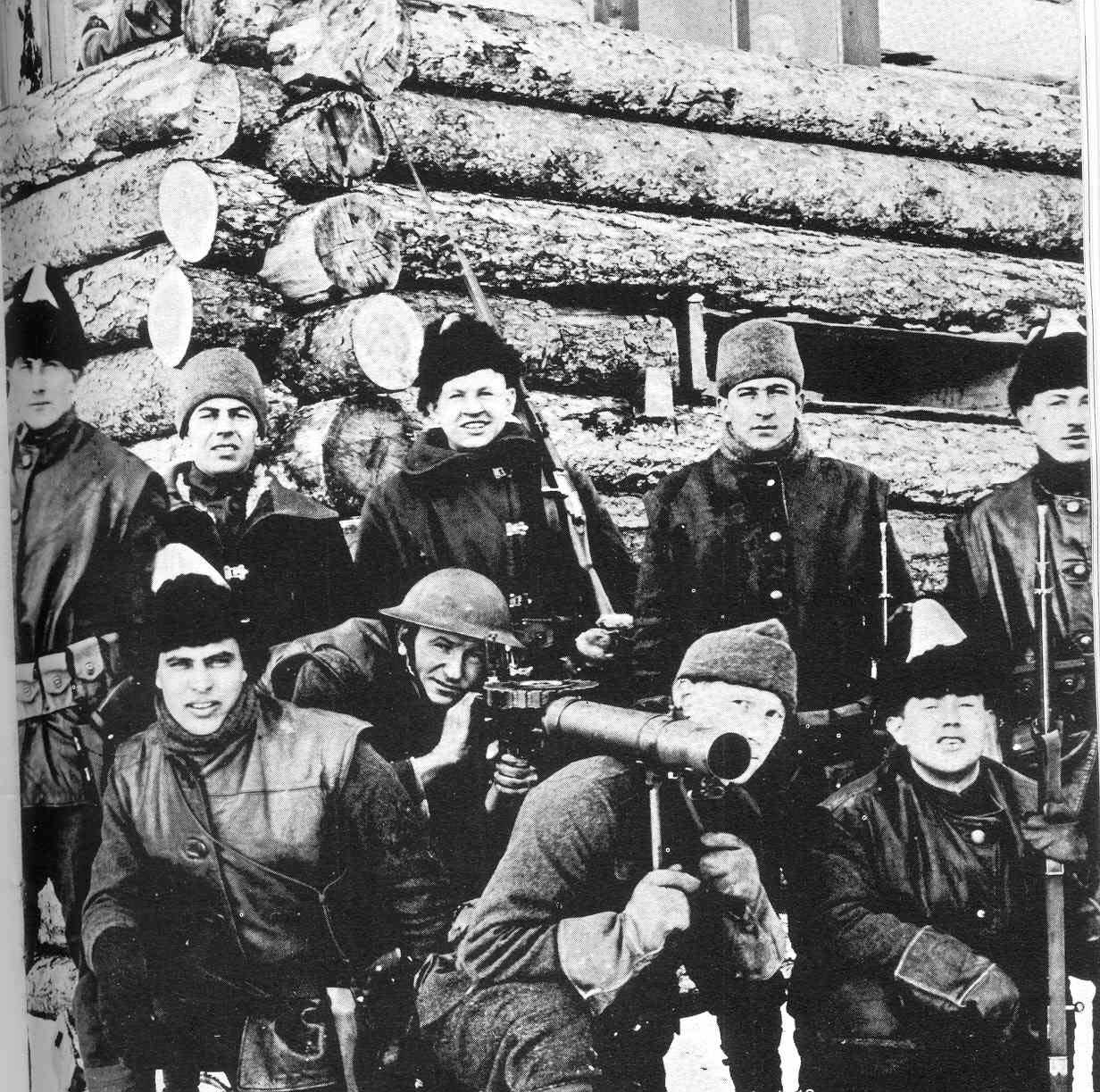

After the Armistice, the Lewis was all but abandoned by the U.S. Army, although a few were used in the ill-fated North Russian intervention in the immediate post-World War I period. On the other hand, the U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Navy retained their Lewis guns, and they saw a surprising amount of combat use between the wars in the hands of Marines and sailors in varying locations around the globe. Lewis guns were part of the armament of the U.S. Navy gunboats plying the Yangtze River protecting American interests in China in the 1920s and 1930s. Marines used their Savage M1917 .30-’06 Lewis guns in a number of small-scale, but often bloody, combat actions in several Caribbean and Central America locales, including Haiti and Nicaragua. The Lewis performed well during in such engagements and provided a much-needed edge to our often-undermanned Marines.

In addition to being used by the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, the Lewis was a mainstay in British service until it was replaced by the more advanced Bren light machine gun beginning in 1935. Nevertheless, many of the Mark I .303 Lewis guns lingered in Great Britain’s arsenals and saw use well into World War II. The Japanese adopted the Lewis gun in 1929, and relatively large numbers were used in World War II by the Japanese navy, primarily for aircraft armament. Most of the Japanese Lewis guns were made by the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal. It is not widely known that Norway also manufactured and utilized limited numbers of Lewis guns in the 1930s.

By World War II, the Lewis was relegated to a second-tier arm in U.S. service. The Marines had replaced their Lewis guns in front-line service with other guns, including the M1919A4 air-cooled machine gun. But a surprising number of M1917 Lewis guns remained in use during World War II, primarily by the United States Navy as secondary armament on landing ships and other vessels.

Any thought that the Lewis gun was incapable of providing valuable service during this period can be easily dispelled by noting that the only U.S. Coastguardsman to be awarded the Medal of Honor, Douglas A. Munro, utilized the Lewis gun in World War II during a heroic engagement off Point Cruz, Guadalcanal, on September 27, 1942.

Even though the Lewis performed yeoman-like service as late as World War II, it was clearly an obsolescent arm and its glory days were long-past. During its prime, the Lewis gun was the best of its type available, as evidenced by its performance in the Great War in the hands of our British and Belgian allies. It is unfortunate, and more than a little ironic given its homegrown pedigree, that our Doughboys and Marines were denied the ability to take the Lewis into battle in World War I. If they had, it is certain the American version of the “Belgian Rattlesnake” would have bitten a lot more of the enemy!