To understand firearm development, it is necessary to have some knowledge of the economy during their progress. The Civil War brought about a great increase in economic opportunities—hence industrialization—to the Union. Manufacturing business grew at a phenomenal rate. The war created a huge market for firearms and fueled the development of their technology. While the waging of war created the demand, it was the Reconstruction period after the war that brought about a maturation of that booming economy. The U.S. military—primarily the army at that time—needed better firearms with which to serve the country.

Single-shot and repeating rifles fed by cartridges that were ignited with a primer pressed into the center of the rear of the case replaced cap-and-ball muzzleloaders and rimfire-primed cartridges. Revolvers—which had progressed nicely into the cap-and-ball technology—began seeing their own cartridge development to centerfire-primed rounds. They were very popular with the cavalry because they could be operated with one hand and offered as many as six shots before requiring a reload.

Colt rather quickly came out with a Benet-primed .44 Colt cartridge for its Richards-Mason conversion of the 1860 Army. The actual diameter of the heeled, outside-lubricated bullet was .451"to .454", and it featured a 225-gr., conical lead bullet in front of 23 grains of FFg blackpowder for a velocity of 640 f.p.s. and 207 ft.-lbs. of energy. Charles B. Richards, an engineer at Colt, and William Mason, a gunsmith who came to Colt from Remington in 1866, worked together on the .44 Colt cartridge, which was introduced in 1871.

The Richards-Mason conversion was a stopgap measure as the company retooled and set up to manufacture what would become the Colt Model 1871-72 Open Top revolver. This revolver was chambered in the more powerful .44 Henry Rimfire cartridge, a major step up in power from the .44 Colt. It was capable of kicking a 200-gr. conical ball bullet out at 1,125 f.p.s. with 568 ft.-lbs. of energy, though these numbers are probably from a rifle.

Buffalo Bore .45 Colt available today loaded with a 255 gr. lead bullet.

Buffalo Bore .45 Colt available today loaded with a 255 gr. lead bullet.

Nonetheless, the army bought several thousand of them for its cavalrymen during the revolver’s two-year production run. Three things became very clear. The army wanted a more powerful revolver. It did not want outside-lubricated bullets that pick up dirt and grit from the field. And a revolver tough enough to stand up to these rigors must have an enclosed window for the cylinder, what we now refer to as a solid frame.

Richards and Mason began developing a new revolver and teamed up with ammunition engineers at Remington to manufacture the cartridges. Both the revolver—the 1873 Colt Single Action Army(SAA)—and its cartridge, the .45 Colt, would become iconic in the annals of firearm development. The .45 Colt retains the bullet diameter of its .44 Colt predecessor at .452" - .454" but kicks the weight of the bullet up to 255 grains.

After playing with loads with bullets as light as 225 grains and powder weights from 28 to 40 grains, they settled on the 255-gr. bullet in front of 40 grains of FFg blackpowder for 840 f.p.s. with about 400-ft.-lbs. of wallop out of a revolver. Production of ammo and revolver began in 1873. The army quickly saw the improvement of both revolver and load, as did civilians, and the Colt .45, as it became commonly called, generated a great reputation as a man-stopper.

All of the preceding did not occur in a vacuum. Smith & Wesson had been hard at work on its No. 3 revolver in .45 caliber. In fact, the army adopted the No. 3 in 1870 chambered in .44 Smith & Wesson American. But the brass wanted more power. Major George W. Schofield had an engineering improvement to the Model 3. Instead of mounting the spring-loaded barrel latch on the barrel, he reversed it and mounted the latch on the frame.

Hornady .45 Colt cartridges loaded with a .255 gr. FTX bullet.

Hornady .45 Colt cartridges loaded with a .255 gr. FTX bullet.

The army specified that the revolver would chamber the .45 Colt cartridge, but the Smith & Wesson revolver’s cylinder was too short do it was chambered in a shorter .45 Smith & Wesson—often referred to as the .45 Schofield, adopted in 1875. The Smith & Wesson cartridge would function in the Colt SAA but not vice-versa. Army quartermasters had headaches trying to sort out ammo for each revolver. Frankfort Arsenal, which supplied nearly all the ammo for the Army, simply ceased loading the .45 Colt and supplied the troops with .45 S&W cartridges.

Somewhere in all of this the .45 Colt nomenclature was colloquially changed to “.45 Long Colt” to differentiate it from the shorter S&W cartridge. From bank heists to battlefields, train robbers to shopkeepers, the .45 Colt and the SAA was king. Sure, there were plenty of those finely made Smith & Wessons, but out on the frontier far from gunsmiths, people counted on the robustness of the SAA and its man-or-beast-busting .45-cal. cartridge.

They must have done something right because, 147 years later, the cartridge continues to be loaded. Other than in wartime, there hasn’t been a hitch in production of the .45 Colt cartridge. The military could not leave well enough alone. Some 21 years after the introduction of the Colt SAA and its .45-caliber round, the military adopted the Model 1892 Colt double-action revolver chambered in a .38 Long Colt cartridge developed in 1875, featuring a 150-gr. lead, round-nose bullet launched by blackpowder at 708 f.p.s. with a measly 157 ft.-lbs. of energy out of a 6" barreled revolver.

Sometime later, a smokeless powder load sent a 148-gr. bullet downrange at 750 f.p.s. and 185 ft.-lbs. of energy. Some bad experiences in the Philippines during the Philippine–American War of 1899–1902 against Moro juramentados tribesmen had the army scrambling for anything that could fire .45 Colt cartridges. This led to Colt developing the M1909 round , identical in load to the original .45 Colt round but with a larger rim to accommodate the star-like extractor/ejector of the New Service double-action revolver.

The author's Ruger Blackhawk chambered for .45 Colt.

The author's Ruger Blackhawk chambered for .45 Colt.

M1909 ammunition will not work in single-action revolvers chambered in .45 Colt because the rim diameter interferes with adjoining cartridges. Even as semi-auto pistols began emerging, the .45 Colt has remained a steady-selling cartridge. Two reasons for that is the reliability and longevity of the SAA revolver and the fact is that it plain works.

Whether dealing with desperados, deer or even black bears, in the hands of a decent shot, a man armed with a .45 Colt will go home to his family or bring home the game. In the mid-1950s, a Utah-based gunsmith and experimenter named Dick Casull began exploring the limits of what a .45-cal. handgun could produce. He started with blackpowder-framed Colt SAAs, re-heat treating the frames and converting them to five-shot cylinders.

In 1959 he introduced the .454 Casull cartridge featuring a case 1.383" long—some .098" longer than a .45 Colt case—and a thicker web in the head of the case that Casull claimed to get more than 1,900 f.p.s. with a 250-gr. bullet. The power guys went nuts over this, but it would take almost 25 more years before this cartridge would be commercially loaded and have a factory manufacture a revolver that could handle it. In the meantime, Ruger chambered its tough Blackhawk revolver in .45 Colt, as did Thompson/Center in its equally solid Contender single-shot pistol.

Power guys ignored the loading manuals of the day and began dropping huge charges of slow-burning powders into .45 Colt cases to see what they could get away with. Now called T-Rex loads by the brethren, many loading manuals gave loads for these guns expressly and specifically. As for me, if I want an extremely powerful revolver—which I do not anymore—I would choose a cartridge expressly made for those tasks. I like the .45 Colt for what it is: a moderately powerful handgun cartridge that does anything I might ask from a handgun.

A view from the muzzle end of the author's Ruger Blackhawk chambered for .45 Colt.

A view from the muzzle end of the author's Ruger Blackhawk chambered for .45 Colt.

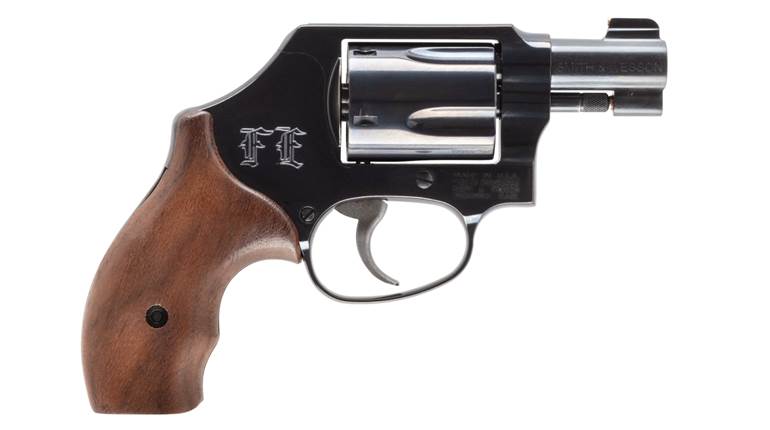

As with all my revolvers, save my J-frame Smiths, I prefer to cast hard semi-wadcutters at some 258 grains in my .45-cal. with 9.0 grains of Alliant Unique powder. In my 4 5/8" Ruger, it gives me about 912 f.p.s. with 476 ft.-lbs. of muzzle thump. If I need more thump, I’ll choose a rifle—too many years of shooting those big bruisers has left me with some arthritis in my hands.

All the major factories load the .45 Colt cartridge today; one of the smaller manufacturers—Garrett, in Texas, loads +P .45 Colt rounds that are expressly for the Rugers. But there are plenty of JHP and SP loads available—outside of the pandemic-induced ammo shortage. There are even relatively soft-recoiling loads for cowboy action shooters. It is the cowboy action shooters that brought another firearm into the .45 Colt fold—rifles.

When the cartridge was introduced, the small diameter and thin rim of the .45 Colt cartridge, along with the straight-walled case, would not feed or extract reliably in the lever-action rifles of the day. Too, it was fueled with blackpowder, which leaves a rather heavy residue. A straight-walled case would often hang up because of that following, especially if the residue was exposed to dampness.

Today, however, Winchester, Uberti, Henry and Cimarron have produced replica lever actions chambered in the big 45. Smokeless powders, some engineering tweaks and the clientele who keep their competition guns clean has largely neutered the old attitude toward .45 Colt lever actions. Continuously produced for nearly 150 years, both in ammo and guns, the .45 Colt remains a capable cartridge for field use or even self-defense. I know several fellows who regularly have a single-action revolver on their belt on a daily basis, and that revolver is a .45 Colt.