Most of the cartridges we see and use today have roots—a lineage that often traces back to some of the first cartridges and their early firearms. Many may know that the .44 Smith & Wesson Special is an updated version of the .44 Smith & Wesson Russian. However, it takes more of a gun geek (like me) to trace it back to its true origins.

By the late 1860s, the notion of a cartridge case with a central primer, often referred to in period advertisements as “central-fire cartridges," was what the future held in store. Rimfire cartridges were prevalent and relatively cheap, but the thin cases could not hold up to the pressures needed to launch large, heavy bullets at velocities needed to do the job at hand.

Smith & Wesson came out with its Model 3 American First Model in 1870. The Model 3 was the first large-frame revolver and was a close competitor of the Colt Single Action Army that was introduced three years later. Its first chambering was in .44 Smith & Wesson American, a centerfire cartridge with a case slightly longer than a .45 ACP and loaded with a 218-gr. outside-lubricated bullet in front of 25 grs. of FFG blackpowder.

Velocity out of a 6.5" barrel was 660 f.p.s., with 196 ft.-lbs. of energy. Both gun and cartridge enjoyed a good reputation for taking the fight out of an adversary, as well as being pretty accurate on the target range. The Model 3 American was used by the U.S. Army from 1870 to 1873, after which the army adopted the Colt SAA chambered in .45 Colt. Nonetheless, the Model 3 remained popular in the American West.

Russia took considerable interest in the Model 3 but found the outside-lubricated bullet a hindrance for soldiers in dirty environments. They specified that the cartridge must have an internally-lubricated bullet. Smith & Wesson obliged the request by shrinking the bullet diameter from 0.434" to 0.429" and lengthening the case from 0.91" to 0.97". Bullet weight increased to 246 grains, and the velocity increased to 755 f.p.s. Christened the .44 Russian, the reaction was quintessentially American—bigger and faster was better.

Smith & Wesson developed some early double-action revolvers like the .38 Double-Action First through Fifth Models, but the top-break action had its limitations. While it was certainly quicker to eject empty casings and reload than the Colt SAA, the Colt’s solid frame was clearly more robust.

Smith & Wesson began working on a solid-frame, double-action revolver in the 1890s, and by 1894, it had the Hand Ejector concept pretty well developed. The first of these were the I- and K-frames for .32 and .38 calibers, respectively. These were solid-frame revolvers with a swing-out cylinder and a spring-loaded plunger that could eject all the chambers simultaneously.

By then it was 1905, and it was time to go big. Smith & Wesson developed a .44 frame to contain a power-house cartridge, yet retain the level of accuracy demanded by competitive target shooters. They lengthened the .44 Russian case -.19", added 0.003" to the thickness of the rim and increased the powder capacity by some 3 grains. The result was the .44 Smith & Wesson Special, or as it is generally known the .44 Spl. It hit the market in 1908.

The revolver and the cartridge were slow to catch on initially. Smith & Wesson has always been fanatical about accuracy and precision. However, accuracy and precision are costly. The .44 Hand Ejector First Model, what we normally refer to it as the Triple Lock, would lighten your wallet by $21, a rather steep price for a revolver at the time.

It was the time of the Panic of 1907 or the Knickerbocker Crisis. This three week event saw a 50 percent drop in the NYSE and created huge runs at the banks. The economy was retracting, and few had the discretionary cash for a fancy new revolver. Economic eruptions run their course, and even arch-rival Colt saw the effectiveness of the .44 Special and began chambering the cartridge in its iconic Single-Action Army in 1913.

Even though it had a larger case capacity the .44 Spl. replicated the ballistics its daddy, a 246-gr. conical-lead bullet at 755 f.p.s. Soon savvy, and sometimes not too savvy, amateur ballisticians realized there was potential in the .44 Spl. Eventually these guys put together a loosely knit bunch of .44 Special geeks of the day and called themselves The .44 Associates.

They exchanged newsletters about handloading the .44 Spl. to its limits. The most noteworthy of these gentlemen was Elmer Keith. He and his friends didn’t just keep adding powder until a revolver blew up; they also set about designing bullet molds that produced a more effect bullet on live targets while maintaining target-grade accuracy. Keith touted the results of this work, as well as similar projects in .38 Special and .45 Colt revolvers, in the pages of American Rifleman and other gun publications.

One of the results of this experimentation was the Keith-style semi-wadcutter (SWC) bullet. These cast bullets were heavy-for-caliber, featuring a large flat meplat and a sharp shoulder. These features, especially with rifling engraved along the shank, acted like a saw and could reliably cut blood vessels and transfer lot of energy, resulting in massive trauma to a live target.

The bullets were cast from an alloy that had a healthy amount of antimony in it, as well as some tin to make the bullets hard and easily cast. In .44 caliber, Keith settled on a 250- to 255-gr. SWC. Lyman made the mold, and it is called the 429421. It is still being manufactured today, and as far as I am concerned, does everything I could ask from a bullet for .44 Spl. or its big brother the .44 Mag.

Fewer shooters handload these days, so what was once available to handloaders exclusively is now manufactured by Double Tap and Buffalo Bore Co. Double Tap’s .44 Spl. Hard Cast Solid features a Keith-style 240-gr. SWC bullet fired at 900 f.p.s. out of a 6.5" barrel and 800 f.p.s. from a 2.5" barrel. Buffalo Bore’s Heavy .44 Spl. Outdoorsman load has a Keith-style 255-gr. hard–cast SWC bullet fired at 1,044 f.p.s. from a 6" barrel and 984 f.p.s. from a 2.5" barrel. But I am getting ahead of myself.

All of this load development eventually spawned the .44 Mag. in 1955. With it in place, the .44 Spl. was like chopped liver. The feeling was, “Why buy a .44 Spl. revolver when you can get a .44 Mag. and shoot either load?” Perhaps many—too many—felt this way, but not the savvy lawman or outdoorsman who puts on a revolver every day.

Those individuals do learn to appreciate the 4 to 5 oz. difference in the weight of the .44 Spl. versus the .44 Magnum. It may seem trivial but after a long day, you’ll notice the difference. The .44 Spl. has a tapered lighter barrel and a slightly shorter cylinder. That extra weight in the .44 Mag. may be welcome when you shoot one, but day after day, it wears on you. Nevertheless, few were purchasing .44 Spl, which became the Model 21 and Model 24 after Smith & Wesson began using model numbers, and the guns were discontinued in 1966.

In the mid 1970s, one Charles Alan Skelton, who went by the nickname "Skeeter" and is the father of noted gunwriter Bart Skelton, began revitalizing the .44 Spl. in his writings with Shooting Times. He put forth a compelling case for the old cartridge and the revolvers specifically chambered for it. Rather suddenly, the demand for .44 Spl. revolvers skyrocketed.

In 1975, I was on the hunt for a .44 Spl. Smith & Wesson. During my year-long search, I found only one with a 6.5" barrel with a firm price of $750. At the time, a brand-new Model 29 .44 Mag. would fetch about $500 on the used market. I eventually did what many others had to do and bought a Model 28 Highway Patrolman in .357 Mag. and had it converted to .44 Spl. As part of the conversion, I had an original 1950T barrel shortened from 6.5" to 5" and added a Combat Trigger, one that is .375" wide with a smooth face.

That .44 Spl. accompanied me on nearly all of my horse-packing trips and rode in a Sam Browne holster during my stint with a small-town police department. It is the most accurate centerfire revolver I own. Several times, it produced groups in the 1.25" range at 25 yds.

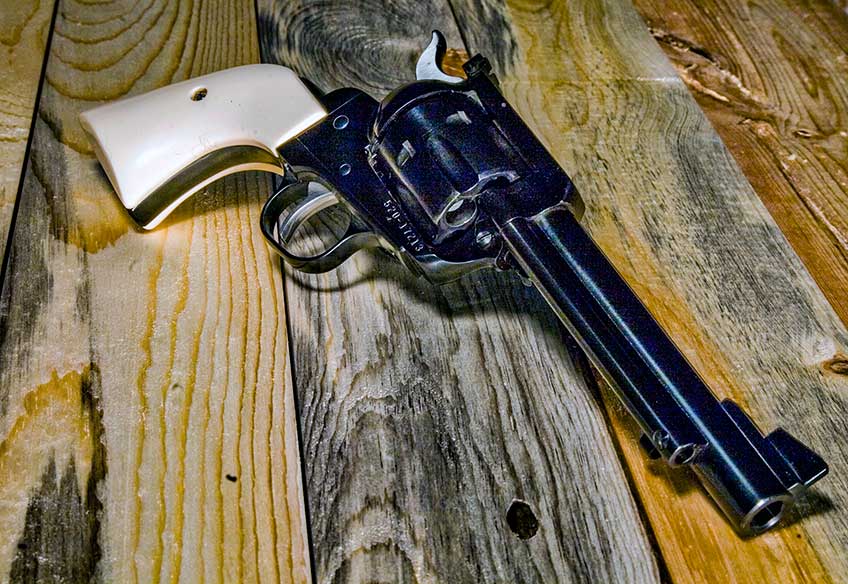

As time rolled on, I acquired more .44 Spl. guns including a 3" and 4" Smith & Wesson Model 24, a couple of Ruger Flat Tops and a Colt Single-Action Army. I have never sold or traded a .44 Spl. and have no plans to.

I've been handloading since 1973, so I have loaded more than a few .44 Spl. cases. Elmer Keith’s old load of 17.5 grains of (at the time) Hercules 2400 behind that Lyman 429421 bullet was fine for hunting. I took a feral pig with it from my Colt about 30-plus years ago, but when I want magnum performance, I use a magnum revolver.

I have not loaded anything like this with Alliant 2400, and I would caution anyone seeking to find the upper limit with modern powders to approach it with caution. What has become known as “Skeeter’s load” consisting of 7.5 grains of (at the time) Hercules Unique behind the same bullet is a fine load, though I see it is no longer listed in modern manuals. Alliant’s Unique has a slightly different burn rate. Since it isn’t listed in the manuals, I cannot publish what I have found safe and effective in my guns, but it’s a little more than Skeeter’s load.

With it I am getting 850 to 930 f.p.s. in my .44 Spl. guns, depending on barrel length. The only big game that this load was used on was as a finishing shot by a friend on a pronghorn because he wanted to preserve the cape for mounting. When I am in bear country, which means grizzly in my neck of the woods, I carry this load. It may not be a T. Rex load that some like to tout for bears, but for shooting a bear or anything else in the face, I am confident that it would be perfectly adequate.

If this has been a bit long and windy for a discussion on a caliber, I make no apology. The .44 Spl. is hands down my favorite cartridge for a handgun. It is accurate, powerful and reasonably easy to control. And after 114 years of service, that’ll do.