Revolver development and sophistication was at a break-neck pace during the last third of the 19th century. The early cap-and-ball revolvers were being replaced by those firing self-contained cartridges. Single-action revolvers were the standard, but trigger-cockers—a.k.a. double-action—began nudging the older ones out. Frames were open topped with a hinge up front to facilitate simultaneous extraction and ejection, followed by rapid reloading. Frames for relatively powerful cartridges were totally enclosed to provide the strength needed to contain powerful loads.

Then as now people clamored for small, lightweight and easy to conceal handguns with enough power to stop an assailant. Those parameters are continually at odds, but an early example of attempting to satisfy all of them was the .38 S&W. The cartridge was designed in 1877 for the spur-trigger Smith & Wesson Model 2 single-action revolver. It wasn’t until 1880 that Smith & Wesson was able to market its .38 Double Action First Model to the public.

The first loads featured a 148-grain lead round-nose bullet in front of enough blackpowder to produce some 685 f.p.s. and 150 ft.-lbs. of energy. These first loads had heeled bullets whereby the bullet diameter was the same as the outside diameter of the case with a reduced-diameter heel held inside the case. The reason for this was the need for more lubricant in blackpowder cartridges. Once the switch to smokeless took hold, the cartridge and groove diameter were matched to the internal diameter of the cartridge case.

A side and bottom profile view of two .38 Smith & Wesson cartridges.

A side and bottom profile view of two .38 Smith & Wesson cartridges.

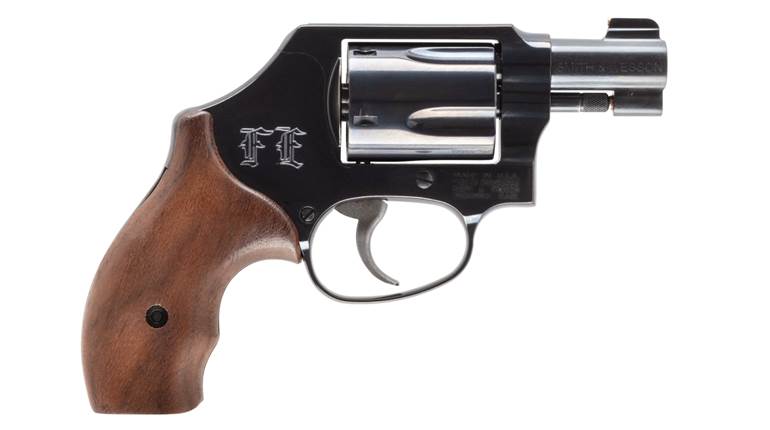

Sales of both revolvers and cartridges were brisk. These revolvers typically bridged a gap between small-caliber pocket pistols—usually .22- or .32-caliber rimfires—and large-caliber revolvers—often called “horse pistols”—that required a holster and belt or a means of attaching the holster to the pommel on saddle. The five-shot Smith & Wesson with a 3"barrel weighed in about a pound, allowing it to easily slip into a coat pocket.

This attention did not slip by other manufacturers. Soon Colt, Enfield, Webley and a host of lesser known companies in other countries began making revolvers chambered in .38 S&W. The name of the cartridge was also changed by some of these knock-off producers. Colt named the cartridge as the .38 Colt New Police; some bastardized the name as the .38 S&W (or Colt) Short; the Brits called it the .380 Revolver and the Belgians called it the 9 mm Revolver. All were the basic .38 S&W cartridge.

After action analysis by Webley of World War I showed that officers—the primary carrier of pistols—liked the power of the Webley Mk IV revolver and its .455 Webley cartridge, however, they wanted something lighter and easier to carry. Webley’s answer in 1922 was to replace the 148-grain bullet in a .38 S&W revolver’s cylinder a with similarly shaped 200-grain bullet, thus creating the .38/200 cartridge. The new cartridge launched that bullet at a lumbering 620 f.p.s. and 175 ft.-lbs. of energy from a 5" barrel. This load remained popular with British officers through World War II and beyond.

A .38 Smith & Wesson cartridge compared with a .38 Special cartridge.

A .38 Smith & Wesson cartridge compared with a .38 Special cartridge.

At the beginning of World War II, the demand for pistols clearly outran the ability to manufacture them in Great Britain. Since Smith & Wesson was very adept at producing its M&P model—technically referred to as the .38 Hand Ejector Model of 1905 Fourth Change—it was simple to bore the cylinders to accept the .38 S&W cartridge. The company produced some 6,125 of these revolvers in September 1940. By the time Smith & Wesson completed the production of .38/200 British Service revolvers on March 29, 1945 some 568,204 copies were made and distributed throughout the British Commonwealth.

Many of these revolvers filtered down to British Commonwealth countries over the years. Quite a few were purchased by U.S. importers and sold as a less costly option for the self-defense market. Some were mutilated by running a .38 Special reamer through the cylinder to allow the American cartridge to be used—bad idea. The .38 S&W is some .0075" larger in diameter at its base than the .38 Special, meaning there is a fairly significant chance of a ruptured case and injury to the shooter or bystanders.

The .38 S&W isn’t an obsolete cartridge technically, but it is no longer nearly as common as it once was. Ammunition—especially in today’s market—is tough to find. Manufacturers have all they can do to keep up with more modern cartridge demands, so if you have an old .38 S&W and find some ammo, save the brass and reload it. The cartridge is one of a few that was born during the age of blackpowder and neatly transitioned into the smokeless powder era.