Eighty-five years have passed since the introduction of the most versatile handgun cartridge of all time. On April 8, 1935, Smith & Wesson announced a brand new high performance cartridge for an equally new top-of-the-line revolver: the .357 Magnum.

In the years preceding that day, there had been a wave of interest in more widespread use of the revolver as a sporting arm and at greater ranges than ever before. Early luminaries of the handgun world—Phil Sharpe, Elmer Keith, Julian Hatcher and Ed McGivern—all contributed to a growing trend.

There was a move toward handloading ever hotter, heavier .38 Special ammunition. The interest convinced the ammo makers to load special heavy .38/44 ammo. Both Colt and Smith & Wesson made large-frame revolvers to handle it.

It was inevitable that the case-capacity limits of the .38 case would be enhanced by just a little more length and therefore, a little more capacity. Also, the new .357 Magnum case would not fit in .38 Special chambers of several smaller, lighter revolvers. Thus was born the most versatile cartridge of all time.

I strongly contend that this is true and I'll give you my reasoning for that belief. We have to start with a review of what happened in the world of revolver-ing since that fateful day in 1935. Smith & Wesson continued to build the gun collectors now call the “Registered Magnum.”

It was a beautifully fitted and finished N-frame revolver with a myriad of options. It is not widely known, but Colt quickly responded with a few Peacemakers in .357, as well as fixed-sight New Services and target-grade Shooting Masters. In the late 1930s, all of these excellent revolvers established the initial reputation of the cartridge.

A lot of these guns went to law enforcement officers, particularly the FBI. Production of the guns and their ammunition went on the back burner in 1941 or early '42. The military services needed handguns, but not highly finished sporting or law enforcement revolvers.

We all know that there were exceptions, like General George Patton's ivory-gripped 3 ½-inch Smith & Wesson. The important thing to remember is the .357 reputation had four-plus war years to build before the guns and ammo went back into production.

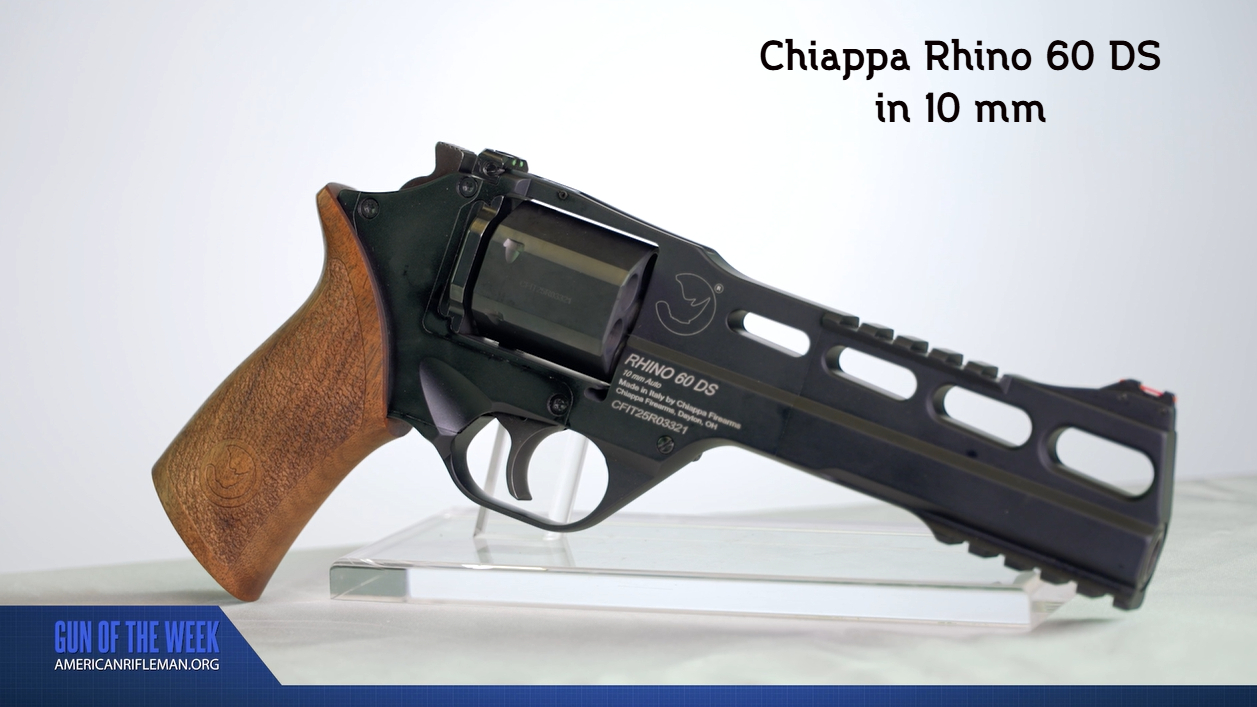

By the mid-to-late 1950s, there were a number of .357 Smith & Wesson models and almost as many Colts. By the 60s, Ruger had joined in and before you knew it, everybody and their brother offered a firearm chambered for this hot centerfire cartridge.

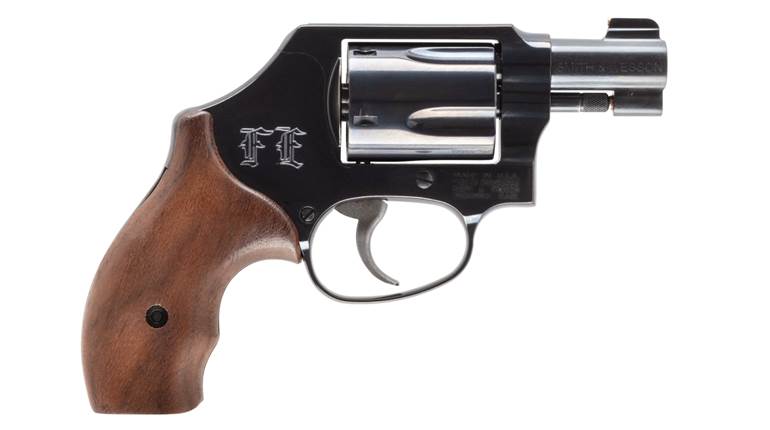

It was widely used as an afield carry revolver, even a medium game hunter. For home and camp defense, it was an excellent choice. By the 1980s, the cartridge had found its way into the five-shot cylinders of most makes of concealed carry revolvers. In some forms of handgun competition, the round was right at home. And of course, the .357 magnum was the modern peace officer's choice in on-duty service armament.

If this isn't versatility, I don't know what is. However, this is not the only reason. Every one of the millions of .357 Magnum revolvers ever made is, ipso facto, also a .38 Special. The original intent of the designers was to create a powerful .357 cartridge that was a fraction of an inch too long for .38 Special chamber. But nothing prevents a .38 Special cartridge from entering a .357 Magnum chamber. Serious implications here.

On the bookshelf just to the left of my monitor, there is a book written by a guy named Bob Forker. I am acquainted with Bob from working with him on another magazine. Named Ammo & Ballistics 5, this book is an encyclopedic listing of every load for every cartridge made.

There's velocity, trajectory, energy and dimensions. It is all about commercial ammo and it's a valuable reference. In the multi-page section on the .357 Magnum cartridge, he lists 72 different loads. They run from an 80-grain Glaser Safety Slug to a 200-grain LWSC. This is an impressive set of choices.

But the section on the .38 Special is even more impressive. It's 80 grains for the lightest bullet weight, through 110-, 125- and 140-grain bullets to traditional 148 and 158 lead slugs. There are a total of 101 .38 Special loads theoretically available to the shopping handgunner.

If he or she is feeding a .357 Magnum revolver, there are 173 different commercial rounds that may be fired through that gun. You are not likely to find them in a single retail outlet. This is one aspect of the versatility question, but there are others.

It is possible to take one good .357 Magnum revolver and a variety of .38 and .357 ammo and compete in several matches in one weekend. Use 180-grain .357 slugs in your revolver for a silhouette (IHMSA) match on Saturday morning and 148-grain .38 wadcutters for a 900-aggregate bullseye match or even a PPC match on Saturday afternoon.

Sunday? Sure, whatever's available—ICORE, IPSC or even Bowling Pin matches. Obviously, I am exaggerating for emphasis, but I remember a guy who shot PPC, NRA bullseye and IHMSA matches with the same 6-inch Colt Trooper III he carried as a working patrolman. The cartridge is versatile.

It even made it into the chambers of several replicas of frontier-era rifles and modern lever actions, as well as a commemorative variant of the elegant Ruger No. 1 single shot. I have been asked by prospective gun buyers who are contemplating the purchase of a concealed carry snubby or general purpose defensive gun: “Is a .357 worth the extra money over a .38?”

Yes, it is. I have at least 173 reasons why.