In October 1940, the U.S. Army began to search for a light rifle with which to arm support personnel. Parameters for the firearm were pretty simple. The rifle needed to be more accurate and have more firepower than the Model 1911A1 pistol, and it needed to be about half the weight of the nearly 10-lb. U.S. M1 Garand or M1928 Thompson submachine gun. No fewer than a baker’s dozen of contenders submitted rifles for the tests.

Simultaneously, Winchester began development of a cartridge to fit this need. Specifications for the new round were to be greater than .27 caliber, with an effective range of 300 yards or more, and a midrange trajectory ordinate of 18" or less at 300 yards. Like many new cartridges, this new one was based upon a pre-existing cartridge, in this case, the .32 Winchester Self Loader (WSL) that was used in the Model 1905, a blowback semi-automatic that enjoyed a rather brief production run of 25 years. The .32 WSL featured a 1.240" long case with just 0.002" of taper from just forward of the extractor groove to the mouth. It also had a semi-rim that was 0.05" proud of the base diameter. The .32 WSL launched a 165-grain bullet at 1,392 f.p.s. with 710 ft.-lbs. of energy.

Winchester turned the rim down to the case diameter, making it we now call rimless, and lengthened the case to 1.28". The 165-grain bullet was also trimmed down to 110 grains. At this point, Winchester was not among the companies submitting a rifle design. Of the 13 rifles submitted for testing, most were unreliable or could not make the weight limit of 5 lbs.

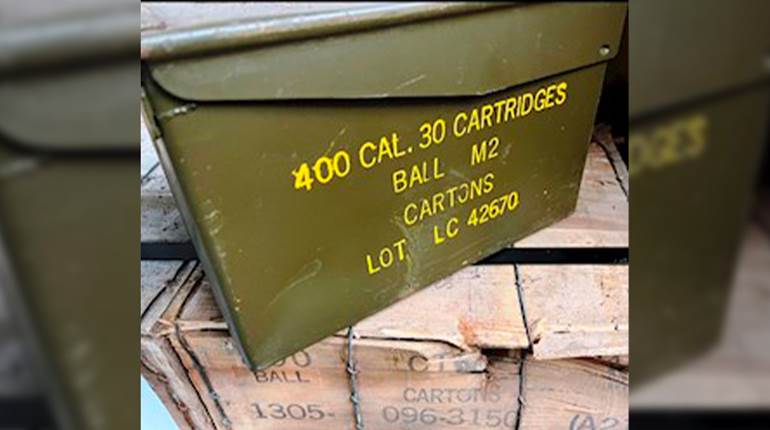

However, Winchester did have a prototype design for an M2 rifle chambered in .30-'06 Sprg. designed by Ed Browning. Major Rene Studler with Army Ordnance asked Winchester to pare down the design, incorporating improvements made by Fred Humeston, William C. Roemer and David Marshall “Carbine” Williams. The result was that, on Oct. 22, 1941, the United States adopted the design as the United States Carbine, Caliber .30, M1, or M1 carbine as we know it now. Despite Winchester being a late starter in the rifle project, it was able to provide a prototype for testing in just seven weeks.

Soldiers loved the lightweight carbine. Since the platform was never intended to be a primary battle arm, there were few reports on its effectiveness beyond 50 yards. Inside 50 yards, the combination supposedly had a 95 percent kill rate. The .30 Carbine cartridge sports more than twice the muzzle energy of the .45 ACP and greater than 10 percent more energy than the later 10 mm Auto pistol cartridge.

The .30 Carbine (center), compared with .45 ACP (left) and 5.56 NATO (right).

The .30 Carbine (center), compared with .45 ACP (left) and 5.56 NATO (right).

With the G.I. ball ammo featuring a 110-grain FMJ bullet at 1,990 f.p.s. out of an 18" barrel, the .30 Carbine has 967 ft.-lbs. of energy at the muzzle. The round-nose FMJ bullets often overpenetrate with no riveting, giving rise to some reports of less-than-desirable stopping power. Recall that stopping power is different than killing power. Targets shot with the .30 Carbine might have that high expiration percentage, but it often takes some time before they expire. Stopping power is the ability to quickly shut down the target’s ability to fight.

After World War II, M1 carbines became available on the surplus market. Civilians—like soldiers—loved the lightweight and fast handling of the carbine. Ammunition companies began offering soft- and hollow-point ammunition for it, so naturally, both carbine and cartridge were tried on deer-size game. With proper bullets, the .30 Carbine can be adequate on smaller deer inside 100 yards. However, M1 carbines typically can hold their shots in just 3" to 5" at 100 yards, meaning the farther the target, the more critical it is to place your shot accurately.

The .30 Carbine first saw use in handguns in 1944, when Smith & Wesson chambered its Hand Ejector revolver for the cartridge. It featured a 4" barrel, yielded 1,227 f.p.s. and 368 ft.-lbs. of energy and produced 4.18" groups at 25 yards. The muzzle blast turned out to be rather intimidating, so any thought of adopting it for military applications was terminated. Ruger began chambering its Blackhawk revolvers in .30 Carbine in the 1960s and continues to manufacture them today. The AMT Automag III was chambered in .30 Carbine as well during its two-year run in the mid-1990s. Taurus produced a Raging 30 with a 10" from 2003 to 2004. Universal and Iver Johnson produced a cut-down pistol called the Enforcer in the 1960s and ’70s.

Handloading the .30 Carbine is pretty easy. Hodgdon’s H110 has historically been the go-to powder, although Alliant 2400, Ramshot Enforcer and Lil’Gun produce good results. Bullets from 85 to 110 grains are all you’ll find. The cartridge does not lend itself toward hot loading; loads should tend toward the maximum to ensure reliable cycling of a semi-automatic action.

Both the carbine and the cartridge have undergone fits and spurts of popularity. Today, the combo sees its most fervent interest with collectors of military arms.