Beyond the obvious effect of muffling a fired cartridge’s report—helping to mitigate the destructive potential of the high-frequency sound waves inherent to using a firearm—suppressors also provide an abundance of other practical benefits that recommend their usage, whether it be on the practice range, in the field or during the heat of the fight. They also reduce recoil, obscure a discharging firearm’s flash to help preserve nighttime vision and, in many cases, even improve the host gun’s barrel harmonics, thereby boosting accuracy. For all these reasons and more, the “silencer” represents the ultimate tactical accessory, which makes Blackhawk’s new line of suppressors the ideal product expansion for a company that has offered a broad range of quality tactical accessories for the past 20 years.

We are currently living during the “golden age” of firearm suppressors. Today, 42 states have laws on the books allowing private silencer ownership, and 40 of those states also permit the use of suppressor-mounted firearms while hunting—figures that continue to climb with nearly every new legislative session. According to the ATF’s “Firearms Commerce in the United States, Annual Statistical Update 2017,” a total of 1,306,023 suppressors, or “cans” as they’re commonly referred to, currently reside in private hands, a sharp, 44.7-percent rise from the 902,805 reported by the same document in 2016. Despite the protracted bureaucratic rigmarole associated with acquiring one and the disinformation spread about them by the entertainment industry and the news media, each year new records are set for both the number of suppressors being purchased by the public and the number of manufacturers producing them—records that will, in all likelihood, be broken again next year.

Of course, all this competition means nothing but good news for the American suppressor consumer, as it results in more quality options on the market, more innovation at the engineering level, lower prices and more mainstream exposure for what is a tragically misunderstood and maligned segment of the firearm industry. Rather than wading tentatively into these highly competitive waters, in late 2016, Blackhawk cannonballed into the realm of silencers by introducing a full suite of seven offerings—models running the gamut from the diminutive, rimfire-compatible Pulse to the immense Wrath, rated to shrug off a regular diet of the potent .338 Lapua Mag. cartridge.

Although they share a few design and aesthetic cues—such as cylindrical body tubes and hexagonal exterior patterning—in addition to a lifetime limited warranty, each member of the Blackhawk family of cans was engineered from inception to fill a specific role. The Pulse is the lone rimfire silencer of the group; the rest are all intended for use with center-fire pistols and rifles. The Barrage is the line’s dedicated .223 Rem.-chambered rifle unit. The Mini Boss pulls double-duty as not only a lightweight .35-cal. (9 mm) semi-automatic handgun suppressor, but, due to its full-automatic rating with both subsonic and supersonic .300 Blackout loads, it is also a capable host with firearms chambered for that rifle cartridge as well. And while both are .30-cal. rifle suppressors rated to handle up to the .300 Win. Mag., the larger, more economical, direct-thread Carnivore is better-suited for use on low-rate-of-fire hosts such as bolt-action rifles, while the more compact, quick-detach-compatible Gas Can is most at home aboard selfloaders.

Hearing loss is permanent and cumulative—the stereocilia of your inner ear, once damaged or destroyed, will not heal or grow back—so any damage to your ear that you suffer, you get to keep forever. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has determined that sound impulses in excess of 140 decibels (dBs) can cause hearing loss after only a single exposure. Given the fact that the great majority of firearms operate at volumes above that threshold, and in many cases far above that threshold, and that silencers, in most instances, can single-handedly serve to bring a firearm’s report down to within the 140-dB safe-hearing envelope, the utilization of suppressors by those who shoot firearms frequently is simply common sense. In fact, it’s hard to believe our heavy-handed government hasn’t yet mandated their use, as it has Hiram Percy Maxim’s other invention that operates under the same principle—the automobile muffler.

Far from actually silencing a firearm, suppressors work to moderately abate a firearm’s report by providing the hot propellant gases produced by the ignition of a cartridge extra space within which to expand. Rather than exiting the muzzle all at once, successive and separate chambers inside the accessory (segregated by a series of baffles) temporarily capture and redirect the gases as the bullet passes, allowing them to transition into the open air over a longer period of time and at a lower temperature. And since our ears interpret a gunshot as a single, loud impulse, spreading out the duration of that sound also reduces its peak intensity and its capacity to cause harm to the delicate structures of the human ear.

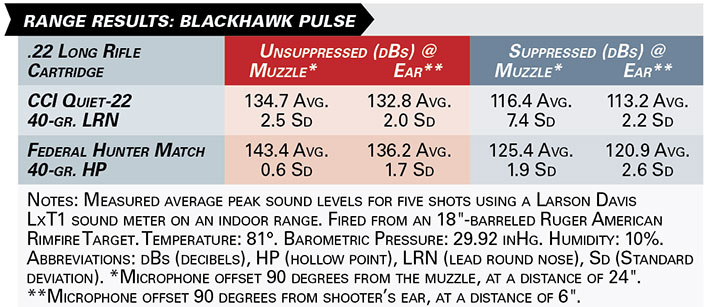

During the past six months, I’ve had the opportunity to extensively test three very different models from the new Blackhawk line: the Pulse, the Gas Can and the Mini Boss—and was even able to use a Gas Can, affixed to a Savage MSR15 Recon, for some prairie dog hunting on the Great Plains of Wyoming. American Rifleman’s protocol for evaluating the effectiveness of a suppressor is to use a sound meter to measure the average volume (in dBs) of a five-shot, unsuppressed group through the host gun (using either a bare muzzle or the included QD mount, as appropriate to the silencer model), at both the firearm’s muzzle and the shooter’s ear, compared to the average of five suppressed shots at the same two locations.

The silencer is allowed to cool down for three minutes between each shot, and all three Blackhawk cans were run through this battery with both a subsonic and a supersonic ammunition load. As it was designed to be easily disassembled by the user, the Pulse was cleaned thoroughly between the two loads using an ultrasonic cleaner; the Gas Can and Mini Boss, which are not meant to be broken down for maintenance, were not cleaned prior to switching loads.

Whenever possible, prior to firing my initial shots through a silencer, I use a suppressor alignment gauge, in this case SureFire’s Bore Alignment Rods (surefire.com; $80), to ensure that the holes in the accessory are concentric with the barrel of the host firearm. If not properly synchronized, the potential exists for a projectile to strike a baffle or the end cap prior to exiting the suppressor—a potentially catastrophic occurrence. I highly recommend their use; you’ve likely been waiting for close to a year for your silencer to arrive, you can take the extra 30 seconds to ensure that it’s not going to immediately blow up in your face.

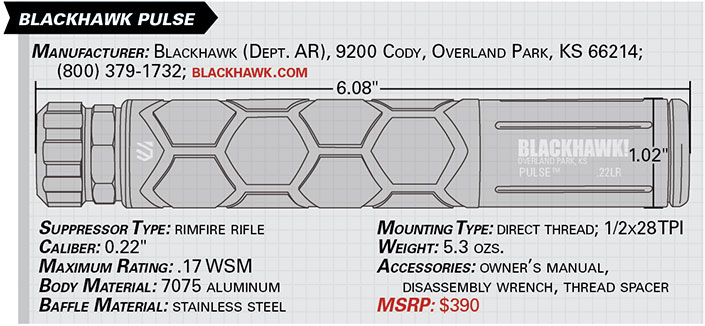

Pulse

Blackhawk’s Pulse is a direct-thread, .22-cal. rimfire suppressor measuring just over 6" long and 1" in diameter, and weighing only 5.3 ozs. Suitable for both pistol and rifle use, the unit’s body tube and end cap are made of 7075 aluminum, while the internal baffles are stainless steel and the attachment mount is carbon steel. Rimfire suppressors do not need to be as hardy as their center-fire counterparts, as the pressures that they must endure are nowhere near as high as those produced by center-fire cartridges, which allows them to be made durably while still keeping the weight down. Magnum rimfire rated, meaning it can handle the relatively powerful .22 WMR and .17 WSM rimfire cartridges, the Pulse is also rated for full-automatic use with .22 Long Rifle—the chambering that it will most frequently be asked to digest.

Rather than go through the process of designing its own attachment mounts and adapters, Blackhawk opted to partner with market leader SilencerCo for those components, and the direct-thread mount on the Pulse is cut to 1/2x28 TPI—a thread pitch that has pretty much become industry standard for .22-cal. muzzle accessories. The silencer is intended for use on hosts with threaded areas that don’t exceed 0.400", however, a thread spacer is supplied for use with firearms with longer threads.

Direct-thread suppressors can be installed by simply aligning the silencer’s threads with the teeth on the barrel and then hand-tightening until snug. This attachment method is ideal for suppressors that will have a dedicated host and that are not expected to frequently bounce around from firearm to firearm. However, for proper alignment, most direct-thread silencers—the Pulse included—require being tightened firmly against a 90-degree shoulder for stability.

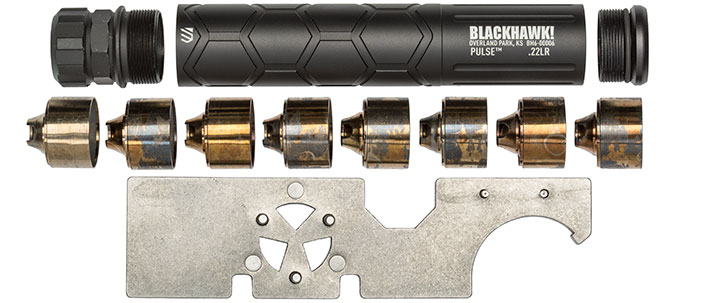

Rimfire ammunition, in general, runs very dirty, which makes frequent maintenance of a rimfire silencer a must. For this reason, Blackhawk made the Pulse extremely easy to disassemble—just twist off the attachment mount and slide the baffle stack from the tube. If further take-down is necessary, the included Universal Suppressor Tool can be used to remove the end cap. The eight, conical, asymmetric baffles snap together while in use, but should be separated for cleaning. The company recommends the Pulse be thoroughly cleaned after every 1,000 rounds fired, and that hydrocarbon-based solvents, rather than ammonia-based cleaners, be used in order to prevent damage to the aluminum components.

The Pulse made several trips to the range during our testing, with a Ruger American Rimfire Target chambered in .22 Long Rifle serving as the host. As demonstrated by the sound-mitigation results on p. 65, the signature of the subsonic CCI load dropped from 132.8 dBs at the shooter’s ear to 113.2 dBs—an impulse low enough to allow our testers to clearly hear their hits striking the steel backstop downrange—while the much speedier Federal supersonic load was brought to a hearing-safe level of 120.9 dBs. The installation of the can shifted the subsonic load’s point of impact up and left only about a half-inch at 50 yds., however, the group jumped approximately 4" straight up with the supersonic load. After every 50-count box of ammunition put through the rifle I checked to see whether the Pulse had started to loosen from its threads, yet only very rarely was re-tightening required.

Long a staple for suppressed shooters, the rimfire silencer is often the first NFA purchase undertaken by those new to the process due to the relative affordability of both the accessory itself and the ammunition fired through it. My time behind the Pulse has revealed it to be an effective, lightweight and durable option for those interested in taking the rimfire suppressor plunge—particularly given its modest $390 price tag.

Gas Can

A .30-cal., center-fire rifle suppressor, the Gas Can may just be the most versatile offering in Blackhawk’s new line. Shipping from the factory with both a direct-thread mount and a fast-attachment-compatible muzzle brake—both threaded 5/8x24 TPI, the most frequently encountered pattern for .30-cal. muzzle accessories—users will have options regarding how to employ the unit. And its .300 Win. Mag. rating (including a full-automatic rating with 5.56x45 mm NATO and .300 Blackout) means that the silencer is suited for use with any center-fire cartridge of .30-cal. or smaller with a lower operating pressure and a smaller case capacity than Winchester’s powerful magnum—a truly expansive assortment of chamberings.

Measuring 6.3" long with a diameter of 1.62", the Gas Can weighs in at 15.3 ozs. with the included quick-detach mount and 13.2 ozs. with the direct-thread adapter. Fast-pitch threads on the exterior of the muzzle brake allow for one-handed installation of the suppressor to a host rifle in only seconds, and a locking collar at the base of the mount assures a snug connection. And, of course, the purchase and installation of additional companion muzzle devices to other firearms allows the can to be swapped between hosts in a matter of seconds.

Built to handle serious pressures, the Gas Can’s tube and end cap are made of 7075 and 6061 aircraft-grade aluminum, respectively, and its mounts are a combination of carbon and stainless steel alloys. The suppressor’s blast baffle (the first in the stack and therefore the one subjected to the greatest dose of heat and pressure) is composed of Stellite, a cobalt-chromium alloy renowned for its resistance to wear and temperature, while the subsequent seven circumferentially welded baffles are made of Inconel, an extremely corrosion-resistant nickel-chromium alloy. A notch cut into the interior of each baffle forces the centerline gases of a fired cartridge to jet toward the edge of the baffle, slowing the gas as much as possible prior to its exit from the suppressor.

Most center-fire rifle suppressors do not disassemble for maintenance, as there is little need, and the Gas Can is no exception—rather, silencers of this type operate at such high pressures that they can be thought of like self-cleaning ovens. What little amount of residue is left by the initial shot is swept from the accessory by the following one, and so on and so on. However, occasional cleaning of the mount may be necessary, and this can be accomplished with a standard gun-cleaning solvent and a brush.

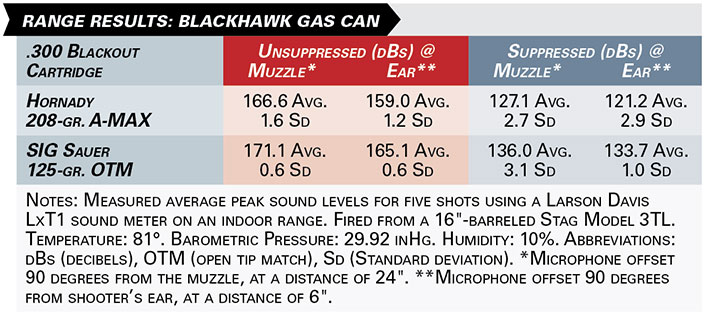

For our range work, the QD muzzle brake was installed to the end of a .300 Blackout-chambered Stag Model 3TL semi-automatic carbine, and the Gas Can was affixed to its host by that means. Through hundreds of rounds of testing, during numerous trips to the range, I did not experience any issues with the silencer loosening from its mount. The Stag also cycled reliably while running the subsonic ammunition, both expelling spent cases and chambering fresh ones without fail, however, the action consistently lacked the energy needed to lock back on an empty magazine.

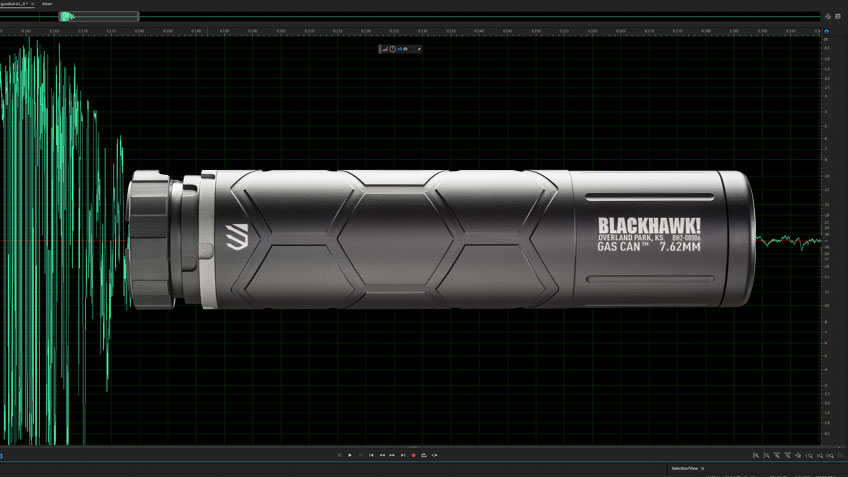

Hornady’s subsonic A-MAX measured 159.0 dBs unsuppressed at the ear, yet experienced an impressive 37.8-dB reduction when fired through the can, for a reading of 121.2 dBs. While not quite as effective with SIG’s supersonic match load, the Gas Can did bring the deafeningly loud report of 165.1 dBs down to a hearing-safe level of 133.7 dBs. Point-of-impact shift with the subsonic load was negligible enough at 100 yds. that it was impossible to rule out the possibility of shooter error, and the supersonic load’s group shifted upward approximately 2" at the same distance.

The .30-cal. rifle silencer has become one of the suppressor industry’s hottest-selling segments, largely due to its extreme flexibility and the inherent value offered by that adaptability. Suitable for use with the plethora of autoloading carbines chambered for the .223 Rem. (with the right mount), .300 Blackout and .308 Win. cartridges on today’s market, as well as with rifles chambered for a vast assortment of popular hunting cartridges—from the .243 Win. and the 6.5 mm Creedmoor to the 7 mm Rem. Mag. and the .300 Win. Mag.—in testing, the multi-platform Gas Can proved itself to be a fine example of its type.

Mini Boss

The Mini Boss is a multi-host, .35-cal. pistol suppressor that, in addition to semi-automatic handguns and pistol-caliber carbines, is also rated for use aboard .300 Blackout-chambered rifles—with both subsonic and supersonic loads—a rare capability among cans of its class. It is also the company’s shortest silencer, standing just 5" long with a 1.62" diameter and a weight of 12.4 ozs. Rated for 9 mm Luger +P loads, in addition to its utility with the .300 Blackout, the unit can also be used with .380 ACP firearms.

Constructed similarly to the Gas Can, the body tube and end cap are aerospace aluminum, the attachment mounts are steel and the internal baffles are a combination of Stellite, Inconel and stainless steel. Attachment of a direct-thread mount allows for use of the Mini Boss with fixed-barrel carbines, while the installation of a piston makes the can ready to accept tilt-barrel self-loading pistols as a host. The silencer ships from the factory with a 5/8x24 TPI direct-thread mount for immediate use with .300 Blackout guns, however, a piston is not included at the time of purchase and must be bought separately.

The added weight of a suppressor hanging off the end of a locked-breech handgun’s barrel will typically cause it to malfunction, and a piston (also called a booster or a Nielsen device) is necessary to ensure reliable functioning. Threading directly onto the host pistol’s barrel, the Nielsen device temporarily decouples the silencer’s weight from the barrel when a cartridge is fired, allowing the gun to cycle normally. However, since different firearm manufacturers often thread their barrels using varying thread patterns, the utilization of the Mini Boss with multiple firearms may require multiple pistons and/or direct-thread mounts. Blackhawk offers a full line of adaptors for this purpose.

Despite its suitability with 9 mm Luger, for the purposes of cleaning, the Mini Boss has more in common with center-fire rifle cans, as its baffles are welded to the perimeter of the tube and are, therefore, not removable. Required maintenance is limited when used with rifle ammunition, however, the company recommends cleaning the piston after each firing session equipped to an autoloading pistol—and this simply requires unscrewing the piston assembly from the rear of the unit.

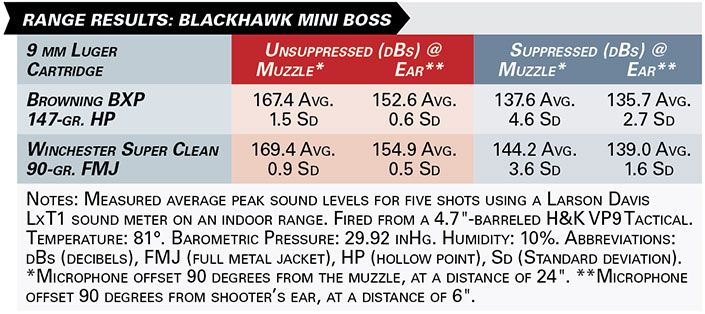

At the range, affixed to a Heckler & Koch VP9 Tactical, the Mini Boss suppressed the subsonic Browning load’s report from a dangerously loud 152.6 dBs at the ear to a much more tolerable level of 135.7 dBs. Meanwhile, the sound reading for the light-for-caliber, 90-gr. Winchester load was 154.9 dBs unsuppressed and a hearing-safe 139.0 dBs when fired through the can. Gas blowback was an occasional issue, however, the piston worked perfectly as intended—functioning of the semi-automatic pistol was 100-percent.

The presence of the suppressor installed at the end of its barrel obviously moved the handgun’s center of mass forward, but—due to the unit’s short stature—it was not so much as to make shooting the gun awkward. The silencer shifted the point of impact of the subsonic load about two inches to the left at 25 yds., and the supersonic load’s group moved about two inches up and one inch left. Blackhawk recommends that the shooter manually re-tighten the suppressor to its host periodically, and I found a quick check after every couple of magazines to be a prudent policy. Care should be taken to avoid potential burns, however, as all silencers heat up considerably during use—even more so during high-volume firing atop semi-automatic hosts.

Many suppressor owners understandably skip over the .35-cal. pistol cans in favor of the added versatility of a .45-cal. model that can typically also handle 9 mm Luger and .40 S&W in addition to .45 ACP. However, for those whose primary handgun is a 9 mm, the compact dimensions of the Mini Boss and its ability to digest all .300 Blackout loads make it worthy of special consideration.

Final Thoughts

Ask anyone you know who owns one or who has spent a decent amount of time behind one, and, to a person, they’ll tell you—silencers spoil you. By comparison, they make unsuppressed fire seem all the more abrasive and jarring. Which brings us to the suppressor’s final practical benefit, not mentioned above: fun. The muffled report, reduced recoil and diminished flash all combine to make a suppressed firearm markedly more pleasant to shoot—and an enjoyable gun is both easier to shoot well and more likely to be trained with often. And improved proficiency with your firearm through increased familiarity is the greatest tactical benefit of all.

Each of the three Blackhawk suppressors that I’ve had the opportunity to put through their paces have demonstrated themselves to be durable, capable performers, priced competitively at their respective MSRPs. And by wisely choosing to hit the market with a full line of models at the ready rather than just a few introductory SKUs, the company has ensured that, regardless of your gun and regardless of your application, Blackhawk has a viable suppressor option available to you.

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=770&height=430&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=150&height=150&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)