The horizon hemorrhaged rainbows as birds lifted from watery havens and suddenly appeared like flapping dragons painted across a fuchsia dawn. First came the teal, flighty and reckless, then lumbering black swans, spanning across the horizon in twos and threes with necks outstretched like unfurled elephant trunks—their six-foot wingspans flogging the air rhythmically in search of morning grub.

Meanwhile, the rising sun cast violet rays on the fantastical world before us, lighting the South Pacific Ocean in the near distance and, with it, the white, gray and auburn hues of the region’s prize: paradise shelducks. Our guide, whose eyes and ears are trained to pick them out at distance, began the distinct, high-pitched series of clucks—screams almost—on his call.

In response, three American hunters, this one included, instinctively hunkered tight to the blind’s thatch like nervous hobbits, and found the safeties on the Super Black Eagle 3s. Not wanting to miss a rare opportunity (how many times would a man make it halfway across the world to New Zealand to hunt ducks, anyway?) I hooked a pinky around the bolt handle to press-check the semi-automatic’s action, making sure a shell was piped—something I’d never do with the original gun. Satisfied, I rode the bolt home and readied for the birds that were now cupped and committed.

While many modern Americans think of New Zealand as the green, mountainous fantasyland where the “Lord of the Rings” movies were filmed, I do not. Rather, I think of it as paradise for waterfowl. And oh, what a venue to field test Benelli USA’s new flagship shotgun it was!

In addition to high-volume wingshooting with both light loads for farm-pilfering pigeons and 3" magnum steel on ducks, geese and swans, New Zealand in July is the opposite of the States. Temperatures ebbed below freezing while rain and sleet pelted us like prisoners. I purposely did not clean the SBE3 once during a week of hunting, but rather abused it with mud and more than 1,000 shots.

While several companies have made a run at the Italian-based firm’s stranglehold on the waterfowl market in recent years after its inertia-action patent expired, it’s my hunch that Benelli will reassume its waterfowl and do-all shotgun dominance with its SBE3. With new features that offer real advantages over previous models, combined with upgrades in reliability, recoil mitigation, handling and aesthetics, I think the SBE has re-established itself as the ultimate waterfowl gun. During each lull in the action between waves of pigeons, I studied the SBE3 to compare it to my experience with the prior two models.

The Eagle Evolves

I bought a Super Black Eagle in 1992 as soon as the Benelli Armi S.p.A. firm worked a deal with Sterling, Va.-based importer Heckler & Koch to deliver a batch to my gun store (December 2016, p. 56). It was the first semi-automatic that would shoot 2¾", 3" and 3½" shells in any order without adjustment; it came with five choke tubes for nearly any situation; it weighed 7 lbs., so it could be carried all day; it wore a then-rare synthetic stock and matte-black-finished steel to survive any environment. I lugged that shotgun countless miles and took scores of game; it’s been dunked, frozen and battered. Because of its proven reliability, “Ben” served as my home-defense shotgun of choice for years.

When the SBE II (March 2004, p. 44) hit shelves 13 years later, it boasted a couple features over the original such as modernized styling, a cryogenically treated barrel and its ComforTech stock system that padded the cheek and was touted to lengthen the recoil impulse, thereby decreasing felt recoil. But with the new and improved features came an “enhanced” price tag, and I didn’t feel these relatively minor improvements (except perhaps for the stock) were enough to render my beloved SBE to the relic rack just yet. (To be sure, plenty of my duck-hunting buddies and, indeed, many other Americans, disagreed with me, as proven by the parade of stylish new SBE IIs in blinds across the country.) Still, my original was functional, and it was paid for. But that’s not to say it was perfect.

After 25 years of abuse, I’ve only generated two complaints about the original. That is, several gobblers have been spared by the rotating bolt head of Benelli’s inertia action. If the bolt is eased into battery, or ridden home, the bolt head can fail to lock fully into battery. The trouble is two-fold; bolt lockup requires forward momentum, and therefore the actual slamming of the bolt fully home—not just a nudge forward—which is quite loud (This is not unique to Benelli, but to all ARs among other guns). Also, its rotational design makes it visually difficult to tell at a glance whether it’s in battery or not. Thus, plenty of hunters have returned from the woods disgusted when, after thinking they were being savvy by riding the bolt home in an attempt to be quiet, were shocked when the gun went “click” instead of “boom.” While I can live with a turkey or a duck getting away occasionally, it’s another thing if you’re defending lives. Secondly, due to its heavy recoil and inertial springs required to handle 3½" shells, it struggled to extract and eject light, 1-oz. loads.

Three’s Little, Classier Brother

Other than its 3½" chamber, stock technology and synthetic furniture, the SBE3 actually has more in common with Benelli’s Ethos model (March 2014, p. 58) than the prior two Eagles. Introduced in 2014, the Ethos addressed a couple of the SBE’s shortcomings by dropping a slightly tweaked action into a more lithe, lively package for upland hunters. But with its 3" action, glossy finish and walnut stock, what the Ethos isn’t is a do-anything, plunge-its-butt-into-ice-water-to-paddle-the-boat gun. That role is reserved for the SBE, and it remains so with version 3.0.

Still, if the Ethos was more intuitive to shoot and bettered the SBE’s action, why wouldn’t the company enlarge its chamber to 3½", remove embellishments, stifle its recoil and bombproof it with a camouflage-dipped synthetic stock? That’s just what the company did.

Make no mistake, while the SBE3 remains one of the most versatile shotguns available, I believe the company decided to make the SBE3 the best gun in one category rather than attempting to do the impossible and make one gun that’s perfect for everything. So Benelli wisely focused the SBE3 on its bread and butter, waterfowling.

As with the Ethos’ bolt, engineers added a spring-and-ball detent to the inside, 5-o’clock position of the bolt body. “It applies rotational pressure to the rotating bolt head,” said George Thompson, Benelli USA director of product development. As a result, the SBE3’s dual-lug bolt head and hook-style extractor lock up to the corresponding recesses of the barrel extension and the shell rim, respectively, with much less momentum required than the SBE and SBE II.

While laying on its side, I couldn’t get the SBE3 to fail to go into battery despite my most gentle efforts. Curiously, I could get the action to fail to lock up when the gun was standing vertically barrel up or barrel down, but then any movement of the gun would initiate the last 1/4" of bolt movement required for lockup. Because of this upgrade, if the bolt is inadvertently pulled back, or if a shooter wishes to be quiet by riding the bolt while chambering a shell, the new bolt’s default is to move into battery to avoid misfiring. This is a significant improvement, especially for those who intend to use this shotgun for home defense.

Scores of articles have been written describing exactly how Benelli’s Inertia-Driven system works, and by now I assume most of you have a conceptual idea of its operation, so I’ll skip its description. It is inherently reliable, however, because it self-regulates according to shell size, it has few moving parts and, unlike gas actions, it blows most shell grime out of the barrel. Really the only negative is that gas actions tend to mitigate recoil better, and that is why I think Benelli has developed other ways of countering recoil. More on that later.

The SBE3’s slender, 9¼"-long machined-aluminum receiver hails from the Ethos, with its arrowhead-shaped joint that combines the upper and lower receivers. The limousine-long upper features an ejection port that’s 3.54" long. Noting that a spent 3½" shell opens to nearly 4", the SBE3’s port is able to accommodate them because the fully retracted bolt recedes behind the port by nearly 1/2".

A spring-powered ejector is affixed to the inside left wall of the receiver that burps hulls with authority. In more than 10,000 shells fired by my group in New Zealand, we experienced not a single ejection malfunction. In fact, to my knowledge only one gun malfunctioned at all, when, on the last day, one particular gun experienced a shell carrier malfunction. It’s become accepted fact that Benelli makes some of the most reliable semi-automatics ever produced. Although Benelli does not guarantee that the SBE3 will cycle 1-oz. shells (1 1⁄8 ozs. is the standard 12-ga. load, and they are guaranteed), I found that the new gun cycles 1-oz. loads 75 percent of the time, which is more than the original did, probably owing to the slightly modified return spring and its cup that’s like the Ethos’ so-called “dynamic” system. It would not cycle 0.9-oz. reduced-recoil loads, but it devoured everything over 1 oz. that was fed to it, including the heaviest 12-ga. shells ever commercially made. Again, this is a shotgun designed for burly waterfowlers who eat fresh goose livers for breakfast.

Certainly, the SBE’s styling is updated over prior models, but most hunters are not wooed by aesthetics alone, and this would seem to explain why hunting gun styling has changed comparatively little during the last century. Hunters tend to be traditionalists, where function trumps form. I’ve always felt the SBE II had a little more Batman-esque styling for the sake of styling itself, whereas the SBE3’s changes are more for a functional reason. Its fore-end is notably slimmer, 1.52" at its narrowest and very subtly flaring to 1.74" near the cap that is cleverly triangular so it’s much easier to twist. The fore-end has a channel for the thumb to lay parallel to the barrel on its top edge. The pistol grip is deep and aggressive with a 90-degree angle. I believe that the closer the head, hands and eyes can be to a shotgun’s bore line, the better the gun can be instinctively pointed and used to down moving targets. The SBE3 is a naturally quicker handling and more intuitively pointing shotgun than was dad’s or gramps’, not that those guns were slouches.

The SBE3 also borrows the Ethos’ oversized controls. Rather than a round, pea-size action-release button, the SBE features a Tylenol-bar shaped, 0.69" job that’s easier to find and punch with a gloved hand or with a finger of the support hand. The 0.57" wide bolt handle and 0.40"-diameter safety button are larger for the same reason.

Also facilitating swift shell loading is the SBE3’s scalloped trigger guard that forms a pseudo-loading ramp. It can help direct the hand and shell to the proper place for loading the magazine by feel alone. From there, the shell can be guided straight forward and onto a loading port that has also been altered. Compared to the old version that was a straight, two-pronged affair, the new gate is a slightly concave design that’s supposed to guide the shell into the magazine with less effort. It features a newly designed two-piece shell latch that reduces the tension required to manipulate it—addressing one common complaint of the original gun, that it was notorious for pinching the thumb between the gate and the magazine tube.

Comfort Tech 3 Stock

The SBE3’s main advantage over most other inertia-action guns, including other Benellis, is its utilization of the company’s patented Comfort Tech 3 system. I know it reduces recoil because I can feel it, so I’ll spare you Benelli’s neat recoil graphs used for marketing. Just shoot a 3½" magnum in the old SBE, then shoot one in the SBE3, and you’ll know it, too. It does so in three ways.

First, it uses a gel-type, springier recoil pad material that dissipates some of the recoil force that hits the shoulder; it spreads it over a larger area, slows the impulse and cushions the blunt force of it. Its 1½" facial wings extend lower than old versions to pad more of the cheek. In the same way, the soft comb insert that Benelli calls “Combtech” cushions the blow of recoil to the shooter’s cheek bone. And while at first I thought this was a simple pillow effect, Benelli engineers actually took great strides to make this comb insert as effective as possible. As I learned after I investigated, the pad itself must be soft enough that it cushions the blow, but not so soft so that it bottoms out on the hard stock buttstock body below; it’s got to have some backbone. Yet it also can’t be so soft that it’s fragile and tears over time.

Benelli’s solution was to design what is essentially a plastic leaf spring that fits under the gel insert, so that the comb material can still be soft, yet it meets spring resistance before it contacts the hard-plastic frame below it. To see this contraption, remove the buttpad by pulling it from the stock, then pull the plastic tab hidden within the buttstock backward. This latch releases the comb insert. Benelli offers combs of various sizes so the shooter can customize gun fit.

The next way the Comfort Tech 3 system mitigates recoil is via a series of 24 chevron-shaped holes that are spanned with rubber dampers. The company says these chevrons make the stock flex slightly and soak up recoil energy, both slowing and dissipating some of its force before it reaches the shoulder. Frankly, however, it’s tough to believe some of this hype, and even tougher to prove it scientifically, but what I can discern is the Comfort Tech 3 has an additional cutout that the previous version does not; it’s a 2.15"-deep, 1/2"-wide cut that traverses both sides of the buttstock just behind the comb. As I demonstrated by holding the gun barrel down on the floor and placing force on the butt, it allows the buttstock to flex about 1/2". Any in-line flexing of the stock creates a spring effect that mitigates recoil.

All told, Benelli says the Comfort Tech 3 system reduces recoil “up to 48 percent” more than the competition. Compared to a 12-ga., 3½", lightweight pump gun, maybe, but to my shoulder 48 percent is too high when compared to top-end waterfowl guns like Remington’s VersaMax or Beretta’s A400 that also have a very soft recoil pad technology, comb inserts and gas-operated actions. However, those guns do weigh more, and we all know that the best killer of recoil is gun weight. What I can say is that I believe the 6-lb., 10-oz. SBE3 is the lightest-recoiling, sub-7-lb., 12 gauge I’ve ever fired, and certainly the lightest recoiling Super Black Eagle. The most apples-to-apples shotgun I can think of is Browning’s excellent new inertia-operated, 7 1/2-lb. A5, and I think the SBE3 recoils less, thanks to the Comfort Tech 3 system. No doubt, Benelli has done as much as any company to reduce the effects of recoil, and its technology is one luxury you pay for when you choose a Benelli over, say, a Stoeger M3500.

Another factor that can influence recoil mitigation, as well as accuracy, is stock fit. Like guns before it, the SBE3 offers a four-piece shim kit that alters the stock’s drop and cast for right- and left-handed shooters. Shooters are remiss in failing to take the time to fit their expensive new shotgun to their body. Not only can doing so make you a more consistent shooter and lessen felt recoil, it can alter the pattern’s point of impact. And the point-of-impact of my particular test gun remains my only concern with the SBE3.

My test gun printed its pattern an average of 6" higher than my point of hold. When I asked Benelli reps about this, they insisted that the gun, with its 0.317"-tall rib, is designed to print about 3" above point of hold, and that shooters should “float the bird” over the fiber-optic front sight pipe. In some wingshooting scenarios where birds are predominantly rising, like in trapshooting, this is a good thing. That’s because on rising targets, the shooter must apply lead above the bird, but if your shotgun places its pattern on point-of-aim, the bird will be hidden from view by the barrel; it’s the reason most bird guns’ barrels are regulated for 60/40 patterns, and trap guns often more than that. While shooters can adapt to shoot nearly any gun well, you should know where yours patterns if you plan to use the gun for, say, turkey hunting, where hunters generally like to place bead on beak and expect something to die. My test SBE3’s pattern seemed excessively high.

I must admit, however, that when reps asked me how I shot the gun on birds, I was honest when I told them I shot it really well. Silence ensued as they rested their case. In relaying my findings to the staff of this magazine, they patterned two SBE3s from inventory and found the central thickening for five patterns on each gun 3" and 4" high, respectively, well within Benelli’s specifications.

I must admit, however, that when reps asked me how I shot the gun on birds, I was honest when I told them I shot it really well. Silence ensued as they rested their case. In relaying my findings to the staff of this magazine, they patterned two SBE3s from inventory and found the central thickening for five patterns on each gun 3" and 4" high, respectively, well within Benelli’s specifications.

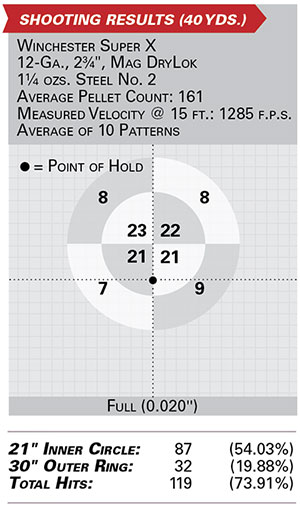

Point-of-impact aside, all five included choke tubes—cylinder, improved cylinder, modified, improved modified and full—produced rich, even patterns with all loads I tried. Two of them, the improved cylinder and modified (the two most commonly used for waterfowl) are the extended type; they give the gun a custom look and are quick to swap. I also tried two additional custom choke tubes, a Skeet II and an Improved Mod from TruLock, and they performed beautifully by delivering unbelievable patterns out to 50 yds. with steel No. 2s.

Action, fit, feel and upgrades aside, there are a couple new features that round out what I’m calling the ultimate waterfowl gun. First, its optional Gore/Sitka Optifade Timber camouflage pattern not only looks killer, but it’s effective in concealing the gun from wary eyes. I realize that staying still is the key to hiding from game—and I also opine that camouflage, to some extent, is fashion for hunters—but I’m convinced that birds see in color. Ducks and geese are masters of spotting movement from high overhead. Good camouflage can conceal movement. As drone footage showed me later, the Optifade blends into most fall environments like a mottled mallard hen on a nest.

Perhaps just as important, the undercoat and plastic film emulsion process, or dipping, protects the gun’s metal finish from rust and scratches, and so I think the Optifade is worth the extra $100. All told, as much as I love my original SBE, I feel like the SBE3 has enough features to be worthy of an upgrade. I was pleasantly surprised when I learned it only costs $100 more than the SBE II.

Sure, going to New Zealand just to hunt paradise shelducks and black swans might seem a little ridiculous to some. But to me, well, I’d rather spend my cash on a hunt and a superior shotgun that’ll last generations than on a fantastical trip to Disney World, where the only feathered game in town is probably named Donald. Indeed, by the way it downed birds with wizard-like efficiency on that faraway island, I’ll forevermore call my new Benelli SBE3 … Bilbo, Lord of the Wings.