The study of ballistics is dedicated to understanding how firearms and their projectiles perform. This includes gathering data related to bullet weights, velocity, kinetic energy levels, rifling twist rates, flight paths and so on. Terminal ballistics, a sub-set of ballistics, focuses more specifically on bullet behavior when it strikes its intended target and how the transfer of the bullet's kinetic energy affects the target itself. This write-up focuses on a few of the more popular types of media used for both formal and informal bullet testing.

Just as you don’t have to be a mechanical engineer to drive a car, so too, bullet tests can be conducted without a physics degree. But it is helpful to understand what types of information can be gleaned from various media along with the advantages and disadvantages they each have to offer. But before we get into the media types, let’s talk about the purposes of bullet testing.

The Purposes of Bullet Testing

Simply stated, bullet testers are striving to generate some or all of the following measurable results:

Bullet Penetration: This is the distance the bullet travels through the media before expending all of its energy and coming to a complete stop. Bullets that under-penetrate are those that do not travel far enough into the test media to meet their design parameters. Overpenetration is when a bullet travels too far or exits the target with enough residual energy to cause unintended collateral damage.

Bullet Behavior: A big part of bullet testing is finding out whether or not a particular bullet does what it's designed to do. Most commercial rifle and handgun bullets fall under one of the following three bullet type categories:

Non-Expanding Bullets

These solid or jacketed bullets are designed specifically for deep penetration. They drive through the target with little or no change in shape or loss of bullet weight. This category is favored for military applications, some types of hunting and pursuits that don't require expanding bullets, such as target competition and casual plinking. Fragmentation or excessive deformation in test media can indicate the bullet is not up to par.

Expanding Bullets

Expanding bullets have tips designed open up, flatten out or 'mushroom' upon impact. These include soft-point and hollow-point bullets along with some more specialized designs. Expanding bullets are intended to increase media disruption while reducing the chances of overpenetration. A failure to expand, minimal amounts of expansion, under penetration or fragmentation in test media may mean that an expanding bullet is not operating as intended.

Fragmenting Bullets

This category includes segmented hollow points and frangible bullets. Segmented hollow points are scored so as to break apart into three or more separate pieces upon impact. This results in multiple wound channels. Frangible bullets are made to shatter into particles of dust, or small pieces, when striking hard surfaces. This reduces or eliminates the chances for ricochet. Unlike the previous two categories, bullets in this class that don’t fragment are failing to perform properly.

Target Disruption (Wound Channel): Bullets are intended to be disruptive. They transfer their kinetic energy into a target with the goal of changing the target in an intended manner. Bullets are used to produce a variety of desired results, such as knocking over steel plates, punching holes in paper, and harvesting big game, to name just a few. How the disruption is quantified, and what form it takes, vary depends on the bullet type and the test media. Soft test media, including gelatin and clay, is useful for preserving a snapshot of what is called a wound channel, or the shape and size of the path of disruption caused by the bullet’s passage through the media. Now let’s dive into the media types.

FBI-Style 10-Percent Ballistic Gelatin Blocks

Back in the late 1980s, the Federal Bureau of Investigations’ (FBI) Firearms Training Unit (FTU) codified a series of ammunition performance tests in which handgun, rifle and shotgun rounds are fired into 10 percent ballistic gelatin blocks. This includes barrier testing or firing bullets through various materials including clothing, dry wall, automotive glass, etc., before impacting the gelatin blocks to see how such barriers effect performance.

Although the FBI did not invent gelatin block testing, their protocols and procedures have shaped how the ammunition industry conducts their tests for military, law-enforcement and civilian applications. As a rule of thumb, FBI testers are looking for defense-grade ammunition projectiles that penetrate to an optimum depth of 12" to 18" while forming a large, disruptive wound channel along the way.

Ballistic gelatin is intended to simulate the effects of bullets traveling through muscle tissue. Gelatin is a protein extracted from pig or cow bones, ligaments, skin and tendons, by boiling them in water. FBI-style 10 percent ballistic gelatin is often made by dissolving 1 part 250 bloom type A gelatin into nine parts of warm water. The liquid mixture is then poured into molds and chilled to 39 degrees Fahrenheit until the gelatin solidifies into usable blocks.

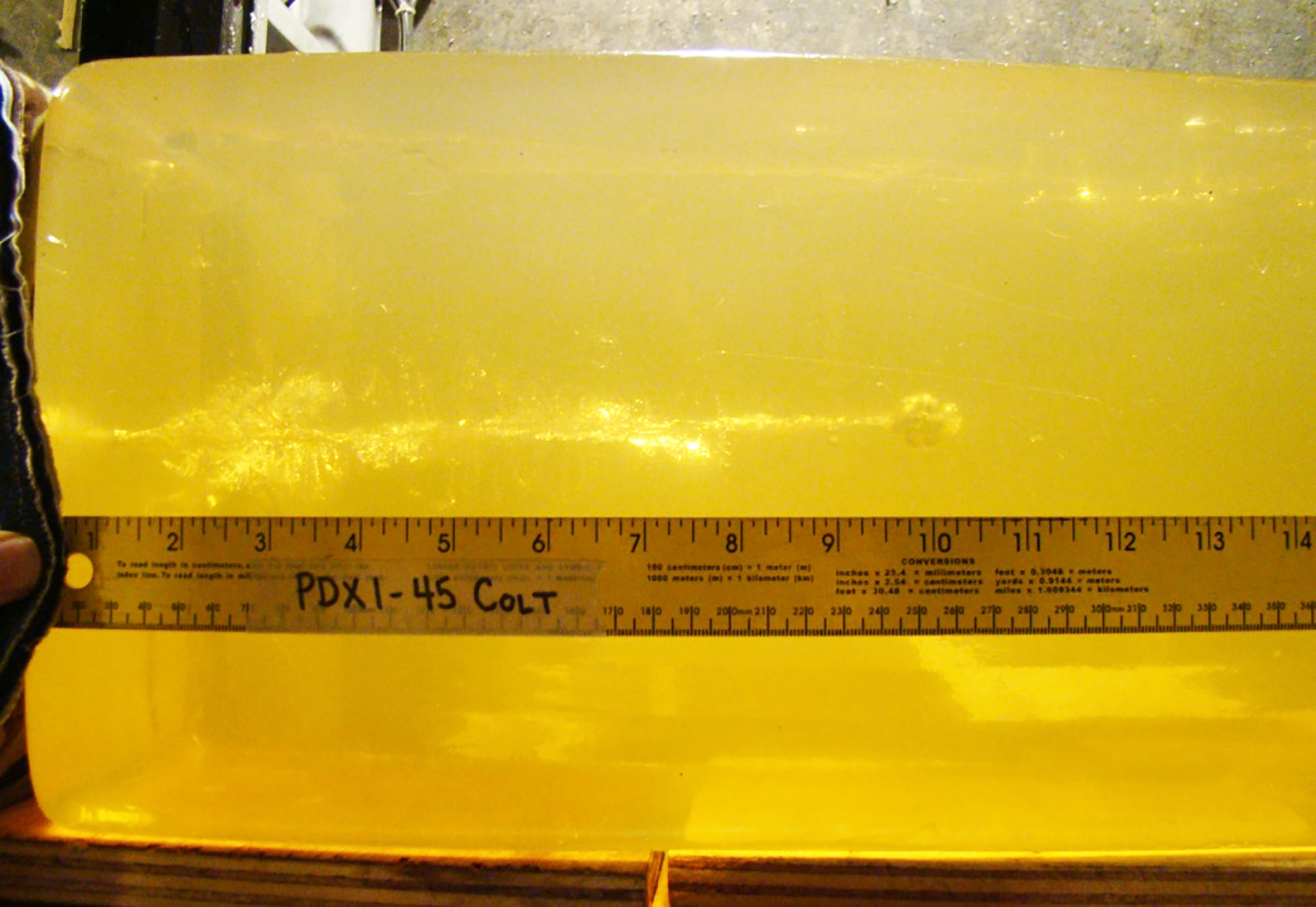

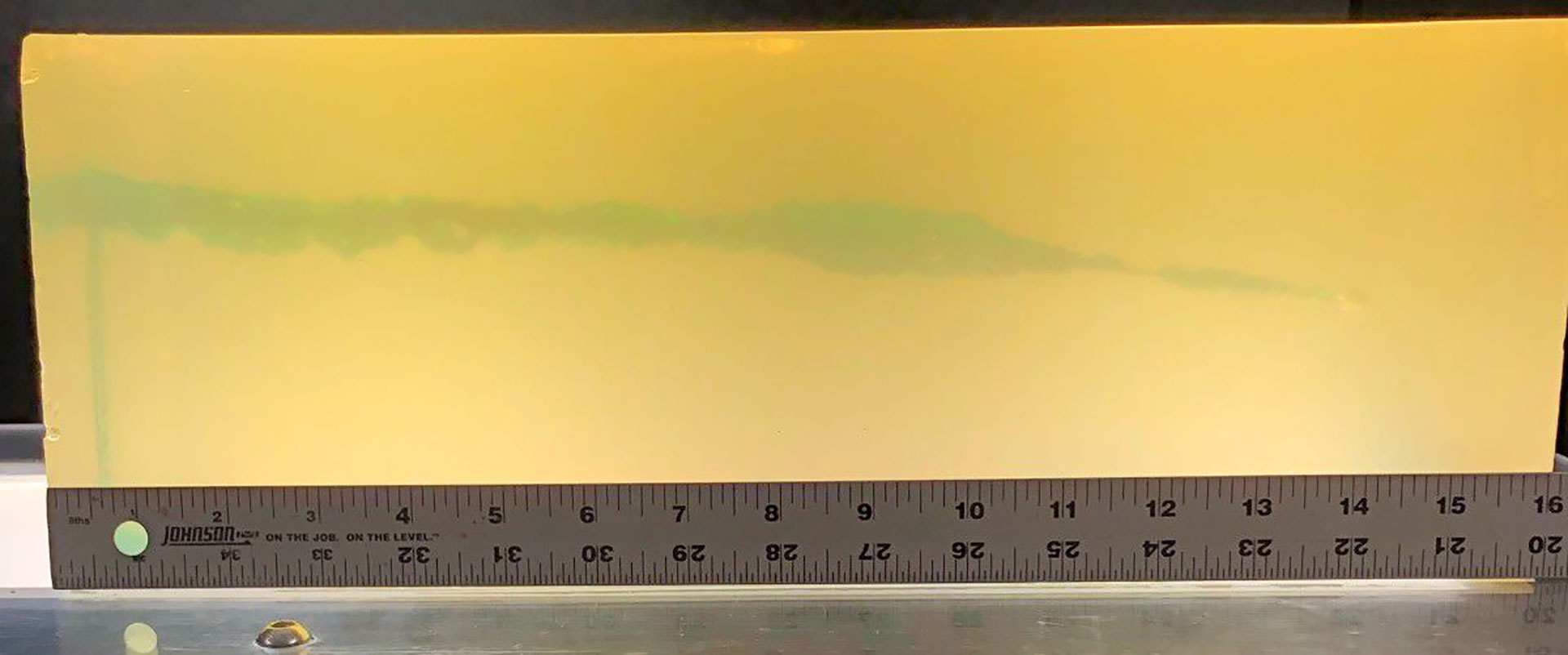

For more than three decades, 10 percent ballistic gelatin testing has been the gold standard for both government and commercial bullet evaluation. The blocks are useful for gathering all three types of test data. Bullet penetration distance is easy to see and measure with a yard stick or tape. Bullets that stop in the gelatin can be pulled or cut out and checked for expansion and weight retention. Gelatin is especially good for preserving an observable wound channel.

But 10 percent ballistic gelatin has several limitations that make it difficult to work with outside of laboratory or dedicated testing facility conditions. It has to be mixed and cooled precisely or it won't be the correct consistency. It must be calibrated and kept within a specified temperature range. The blocks are somewhat opaque, making it more difficult to see where the bullet stopped. If properly refrigerated, the blocks only have a working life span of about 7-10 days. They cannot be re-used and, quite frankly, they don't smell so good. Handling these blocks can leave you needing a shower and a change of clothes afterwards.

Two: Synthetic Gel Blocks

Synthetic ballistic gel blocks are designed to solve many of the challenges inherent in using protein-based gelatins. Clear Ballistics makes a synthetic that I've worked with for several years. Their gel is completely transparent, odorless, colorless, and it’s shelf stable at temperatures ranging from -10 degrees to 95 degrees Fahrenheit. It is also reusable. The gel blocks can be melted down and re-molded many times. It will eventually start to take on an amber hue from repeated heating but that will not affect its consistency.

Over the last few years, synthetic gel has become a popular test media for the shooting industry and content providers. It's easy to see where the bullets stop and to take photos or videos due to the material's transparency. The gel does not spoil or get moldy, so it can be used for bullet performance displays at trade shows or stored for long periods of time. I enjoy working with it for bullet tests like this one.

However, synthetic gel tends to be a bit more elastic than protein-based gelatins. As a result, it does show bullet penetration and upset quite nicely but does not preserve the wound channel nearly as well. The re-molding process can be time consuming, and it's relatively expensive to buy synthetic gel along with the molds and melting equipment. The products quickly pay for themselves for folks who get paid to generate bullet test results for print or website content. But it may be too much of an investment for more casual hobbyists or those who want to evaluate a hand-loaded hunting round or two.

Three: Clay Blocks

Clay blocks, including modeling clays (oil plus minerals) and pottery clays (water plus minerals) are the poor man's ballistic gelatin. As the photo shown here demonstrates, clay yields immediate and often impressive results. It is stable at a wide range of temperatures, relatively inexpensive, easy to find at craft supply stores and it is reusable. Just pat it back into shape and you're ready to go. Although the blocks are opaque, it's easy to cut them in half with a wire or knife in order to see a cross section of the wound channel.

Clay blocks can be useful for side-by-side bullet comparisons, like this .22 Mag. rimfire ammunition test. Seeing how the blocks responded to the different loads is informative. Unfortunately, clay blocks are inconsistent. Testers working at different facilities can produce, or reproduce, comparable bullet test results using FBI 10 percent ballistic gelatin because the blocks are made using a shared formulation that maintains consistency.

Clay varies as to its composition, moisture content and density from block to block. Shooting the same ammunition into clay blocks from different suppliers will yield different results. How well clay simulates muscle tissue is not well understood, and the mineral content makes it significantly more abrasive than protein-based gelatins or synthetic gels. This means that expended bullets may not exhibit the same shape or weight retention one would expect if tested with a different media. But due to its low price and easy access, it can be a useful test media for folks who would like to conduct less formal bullet testing while avoiding the costs and inconveniences of working with gelatins.

Four: Water Jugs

Firing bullets into water jugs is one of the most commonly used bullet test methods today for professional media members and amateurs alike. Years ago, wet-paper was often the low cost choice for budget-friendly bullet testing. Now that stacks of old newsprint and out-of-date phone books have gone the way of the dodo bird, water jugs top the list.

Test methods include shooting into individual jugs, to judge energy transfer, or lining up several jugs in a row to also check for bullet penetration and behavior. Water is a terrific media for catching expended bullets for evaluation. Expanding bullets tend to mushroom much like they do in muscle tissue, even though the penetration distances may not be exactly the same.

Water jugs are plentiful and cheap to buy. Anyone who wants to conduct a bullet test can use them without much in the way of expense or inconvenience. Unlike the previously mentioned gel and clay media, water does not preserve a snapshot of the wound channel like gels or clay. However, jugs can display energy transfer quite dramatically. A low-energy bullet will simply punch a tidy little hole in a jug. But a high energy round can cause one or more jugs to split open or detonate like a hand grenade. Clean-up is easy, too. Just pick up the empty jugs and dispose of them properly.

The scientifically minded among us will point out that differences in jug sizes and polymer composition, along with water mineral content, temperature, etc., introduce too many variables to make water jug testing repeatable. Fair enough, but jug testing isn't exactly precise for other reasons.

The common, budget-priced water jugs where I live are the same in shape and composition (a semi-soft polymer) as the one-gallon milk jugs. They provide, roughly, a 6"x6"x3" block of water contained between the base of the bottle and the lower portion of the molded in carry handle. When a bullet stops inside of a jug, without marking or lodging into the opposite side of where it entered, then there's close to 6" worth of guess work regarding bullet penetration.

Nevertheless, members of the shooting community at large (including me) are perfectly happy to keep blowing up water jugs in front of a camera. Despite its limitations, water-jug testing is easy, affordable and fun to film in slow motion.