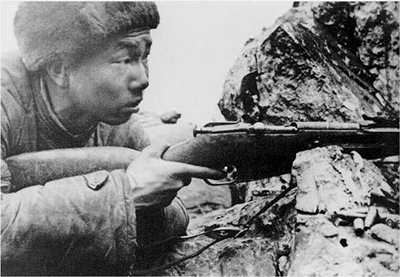

The M1C rifle saw little use at the end of World War II, but it saw considerable service during the Korean War, such as with this U.S. Army sniper in 1950.

There was little sniping in the Korean War—at least during the war’s initial six months. On June 26, 1950, the North Koreans invaded the South, nearly overrunning the peninsula. In September, American-led United Nations forces landed to their rear at Inchon, cut them off and then invaded North Korea. Then, in November 1950, with the U.N. forces on the verge of victory, a half-million Red Chinese troops intervened, throwing Allied forces 250 miles southward.

By early spring 1951, this ebb and flow finally stabilized near the mountainous 38th parallel, where both sides dug-in on high ground overlooking wide valleys—ideal sniper country.

But where were America’s snipers? There were almost none.

The Commander’s Prerogative

Problem was, as a 1951 United States Marine Corps study observed, in the new atomic age, “The Marine Corps no longer trains snipers, nor are such personnel designated in TOEs [Tables of Organization].” The U.S. Army likewise offered no sniping guidance, no selection standards, no sniper schools and no sniper slots. Sniping was, the USMC Tactics and Techniques Board determined, “the prerogative of Commanders.”

The Garand’s top-loading action greatly complicated scope mounting. The Army initially tried a prismatic sight with an offset scope body, but eventually settled on an offset Griffin & Howe side mount.

Thus, it was up to individual field commanders in Korea to select and train their own snipers, with no outside support. The earliest Korean War sniper school I’ve found was formed by 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, in April 1951, 10 months into the conflict, amid the Chinese spring offensive. Since the 2nd Battalion had 18 scoped rifles, this was the class size. Hopefully, the battalion could draw upon competitive riflemen or World War II sniper veterans as instructors, but imagine their challenge: In the early 1950s, few American riflemen had any idea how to use such an expensive, novel device as a riflescope. The 2nd Battalion’s one-week course, though hardly more than a rifle and optic familiarization, at least was a start.

Other 1st Marine Division units soon followed, convening more sniper courses, but due to ongoing combat, little more than a week could be spared. Select marksmen were brought to the rear, hastily instructed and sent back to their units with brand-new sniper rifles.

In Korea, Capt. William Brophy fitted a .50-cal. barrel to a captured Russian PTRD Model 1941 in an attempt to create his own sniper rifle—see the sidebar below for more details.

The U.S. Army, too, initiated sniper training, with the 2nd and 25th Infantry Divisions soon launching their own schools. In early 1952, after dodging a Chinese sniper’s bullet, the commander of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines set up his own school: a three-week course that addressed far more than weapon familiarization, with students training on M1C Garands, bolt-action Springfields and a scoped .50-cal. M2 machine gun.

Returning to their units, these newly trained snipers had no slots—no permanent assignments except for how each Marine and Army battalion commander organized them. Initially, the number of battalion snipers was dictated by the unit’s available sniper rifles. Thus, the 1st Marine Division’s 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, created six two-man teams for each rifle company, with two teams in each rifle platoon.

The Korean War U.S. Army 1903A4 Springfield sniper rifle was identical to the World War II version except for its 2.5X Lyman Alaskan scope (top). Originally developed as a Marine target rifle, the M1941 sniper rifle employed an 8X Unertl scope, which offered three times the Lyman scope’s magnification (above).

By contrast, its sister battalion, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, carried its scout-snipers in the battalion Weapons Company, with 12 teams of two men each, forming three squads with four teams per squad. They were deployed wherever the battalion commander thought best. A year later, the 5th Marine Regiment consolidated training and formed “Sniper Group/Platoons” within each battalion.

The Army, too, lacked slots, although there was one sniper rifle per 11-man infantry squad, with that rifle issued to a squad rifleman as an additional duty. If this part-time sniper proved to be effective—or had attended a sniper school—his job usually became permanent. Any organization beyond this was, “the commander’s prerogative.”

Squatting beside his dented helmet—struck by a Chinese sniper’s bullet—USMC T/Sgt. John Boitnott reloads his M1C sniper rifle. His scope is a Lyman Alaskan M81.

Rifles And Optics

America’s snipers went into combat with both bolt-action and semi-automatic rifles. The Army bolt-action, the U.S. Rifle, Cal. 30, Model 1903A4 Springfield, was identical to its World War II configuration but with a better optic. Gone was the M73B1 (Weaver 330) scope, replaced by a military version of the 2.5X Lyman Alaskan, dubbed the M81 (crosshair reticle) or M82 (post reticle). The Lyman functioned identically to its commercial cousin, except it had target dials—adjustable for one-minute-of-angle (m.o.a.) increments. To accommodate the scope, the Springfield’s rear sight base was milled flat and the receiver ring tapped to install a simple bridge mount.

Despite its 5" eye relief, the ocular (rear) bell was fitted with a rubber eye cup. Early M81 and M82 scopes were blued, but later production added a matte finish and extendable sun shade.

Cradling an M1C rifle, a 1st Marine Division sniper and his spotter lie hidden in foliage overlooking a Korean valley.

The Marine Corps fielded its own bolt-action sniper rifle, based on the Model 1903A1 Springfield, distinguished from Army A4 models by its ladder-style rear sight forward of the receiver. Designated the M1941, it had been developed a decade earlier as a competition rifle and was topped by a Unertl 8X scope with micrometer-like target knobs and an adjustable focus. Due to its protruding knobs and lengthy tube, some thought the Unertl more susceptible to damage than the Lyman, but the trade-off was substantial, as it featured triple the magnification of the Lyman scope. Although not officially a “prescribed” USMC arm, Korean War-era Marine divisions were authorized 100 Springfield M1941 rifles fitted with the Unertl target scope.

Both the Army and Marine Corps employed the semi-automatic M1C sniper rifle, a modified version of the trusty M1 Garand. The M1C, refined during assembly at Springfield Armory, offered a 4-lb., 8-oz., to 6-lb., 8-oz., trigger pull, versus the standard M1’s 5-lb., 8-oz., to 7-lb., 8-oz. pull. A Lyman Alaskan scope and mount increased the weight from 9 lbs., 8 ozs., to 11 lbs., 13 ozs. With the Lyman scope and trigger job, the M1C cost $120.68 more than the standard Garand. The Army eventually authorized 27 M1Cs per infantry battalion.

Unlike the bolt-action Springfield rifle, the M1C loaded and ejected an eight-round clip vertically—which precluded placing a scope directly above the receiver. This was solved by positioning the optic to the left using a unique Griffin & Howe mount. Attached to the receiver by three screws and two pins, the G&H baseplate incorporated a dovetail slot on which its quick-release mount slid and then was locked with dual levers.

To accommodate the sniper’s cheekweld and eye alignment with the scope, the M1C included a leather cheekpad laced atop the butt. This undoubtedly took some time for a sniper to get used to, but apparently worked just fine.

To reduce muzzle flash, the M1C was issued with either a cone-shaped M2 or a prong-shaped T37 flash suppressor, held in place on the bayonet stud. These were often removed because snipers found they worked themselves loose, resulting in harmonic vibrations that degraded accuracy.

The M1C Technical Manual, TM9-1275, recommended a 300-yard zero for the M1C, which approximates a point-blank zero for the .30-cal. M2 cartridge—ensuring a likely hit from the muzzle to perhaps 360 yards. However, due to the scope being mounted left of the bore, windage was only true at the zero distance, beyond which the bullet path angled to the right. The farther the target, the greater the deviation. Thus, for long-range shots, the sniper had to adjust both elevation and windage—or, as was often the case, hold left to compensate for the deviation.

Stateside, the Marine Corps developed its own variation of the M1C, designated the M1952, its greatest distinction being its scope, a military version of the 4X Stith Bear Cub. This scope, designated the “Telescope, Rifle, 4XD,” employed the same Griffin & Howe mount as the M1C, and likewise positioned the scope to the left of the receiver. According to American Rifleman Field Editor Bruce Canfield, the M1952 went into production too late for Korean War service.

As for ammunition, the war’s primary American sniper round was the standard 150-grain M2 ball, which typically achieved groups of four m.o.a. or larger. Based upon student marksmanship during sniper training, the M2 ball could be fired to a maximum of 600 yards with the shooter likely to score a hit. However, many snipers thought the 163-grain, black-tipped, armor-piercing round could achieve better long-range accuracy.

Snipers In Action

By the summer of 1951, American snipers had made their presence felt, especially in the “Battle of the Outposts,” with familiar names like Old Baldy and Outpost Reno. A major sniper mission was dominating the area between the lines to thwart enemy reconnaissance and disrupt infiltration attempts. On outpost duty, they typically operated from first light to sundown and then withdrew to the unit’s main position. Touring an outpost, a Marine commander was especially impressed by his snipers’ “camouflaged bunkers which protruded only a foot above the ground’s surface. These were artfully concealed and the occupants entered or left only in darkness.”

At night, snipers usually rested unless called upon to support their infantry comrades in repelling enemy attacks. However, during periods of good moonlight, or while parachute flares illuminated the area, their low-magnification Lyman scopes significantly improved their ability to discern targets. On cloudy nights, a tank’s brilliant xenon searchlight (even from a mile away) provided sufficient reflected light off cloud bottoms for sniping engagements. The night did not belong to the enemy.

Sniper teams often accompanied daytime squad patrols, providing overwatch or—vice versa—the squad provided security while the sniper team engaged distant enemy targets. In particular, USMC sniper L/Cpl. Juan Alvarez, recalled that his daytime patrols hunted Chinese forward observers who directed enemy mortar and artillery barrages on U.S. positions.

In offensive action, snipers supported their platoons and companies, providing covering fire, especially to engage machine guns and crew-served weapon positions.

At times, their worst enemy was the weather, with winter temperatures reaching -30o F. Corporal Ernest Fish, a Marine sniper, could hardly remain in a prone position, recalling, “You stuck to the ground if you lay there too long.” Lubricants themselves sometimes froze, rendering a rifle useless.

Still, America’s snipers proved their worth. Marine M/Sgt. Bradley Westerdahl was credited with killing 17 Chinese and North Korean soldiers. Wounded twice, after returning stateside he shot in competitions, earning his Distinguished Rifle badge in 1952.

Army SFC Chester Hamilton had been a Distinguished Rifleman before being assigned to the 7th Infantry Division. During one engagement, shooting his new M1C, Hamilton spotted Chinese soldiers crossing a ridge, silhouetted against the sky. In a series of shots, which he likened to a carnival shooting gallery, he knocked them down, one after the other, until, he estimated, he’d hit 40 enemy soldiers. In 1953, seriously wounded, he returned stateside but continued his competitive shooting career for another 25 years, including winning the NRA’s 1,000-yard Wimbledon Match in 1962.

Perhaps the war’s best-known sniper—another pre-war Distinguished Rifleman—was T/Sgt. John E. Boitnott of the 5th Marine Regiment. While stationed at Outpost Bruce, a visiting war correspondent photographed Boitnott’s novel tactic of drawing enemy fire by having his teammate, PFC Henry Friday, trot along their trench. Hunkered down, eye to his scope, when a distant enemy soldier rose to the bait he met Boitnott’s dead-on shot. For three days they continued this tactic, scoring nine kills at up to 1,250 yards. Senior officers put an end to this after reading about it in the newspapers. But Boitnott’s long-range shooting continued, and, as his battalion’s staff journal recorded, during one four-day period, firing only 12 rounds, he was credited with eight more kills.

Having begun the war with literally no sniping capability, America’s soldiers and Marines trained hard, studied and mastered their shooting, stalking and fieldcraft skills. As the commander of 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, noted, once his snipers went to work, “In nothing flat there was no more [enemy] sniping on our positions.”

Using the tripod’s Traverse and Elevation Mechanism, a scoped .50 cal. allows fine adjustments, measurable in mils of elevation and windage.

Fighting Fifties

Due to Korea’s terrain, the front lines often faced each other at 1,200 or more yards, well beyond the M1 rifle’s maximum range. This inspired perhaps the war’s greatest sniping innovation: employing the .50-cal. Browning machine gun as a long-range sniping arm. Lacking portability—the tripod and machine gun together weighed 127 lbs.—it was suited only for firing from fixed positions. Each infantry company was authorized one .50, but more guns were at the battalion level, depending on the type of unit.

The 50’s 709-grain bullets generated five times the energy of .30-cal. projectiles and were half as susceptible to wind drift. Even at 1,500 yards, a .50 was a bunker-buster, penetrating 21" of soil or 6" of dry sand.

These guns typically fired five- m.o.a. groups—5" at 100 yards—hardly a precision arm, yet the gun’s tripod included a Traverse and Elevation Mechanism that allowed a steady hold and repeatable shots. The elevation wheel offered 50 mils of elevation at one mil per click, while the traverse bar allowed 500 mils of windage right or left. Using his .50’s T&E Mechanism, Marine Sgt. Joseph Eberlin found, “We could squeeze off one round at a time with tracer bullets [and] could zero-in on a target more easily.”

A U.S. Army company commander, Capt. Kenneth Mertel, witnessed considerable success with his unit’s .50s. Assigning one scoped .50 to each of his three infantry platoons made life difficult for any communist soldier firing potshots at his men. A Marine Corps battalion commander whose unit experienced continuing enemy sniper fire deployed scoped .50s in his forward lines and, “In nothing flat there was no more sniping on our positions and nothing moved out there, but we hit it.” Eventually, the .50 proved to be so effective that the 1st Marine Regiment’s sniper school added the gun to its curriculum, with students firing to 1,200 yards.

One especially effective engagement technique was simultaneously firing two separately emplaced .50s at the same target, which doubled the odds of a hit and confused the enemy as to the guns’ locations.

While serving in Korea, U.S. Army Ordnance Capt. William S. Brophy, a heavy-rifle pioneer, fitted a .50-cal. barrel to a captured bolt-action 14.5 mm Russian-chambered PTRD Model 1941 anti-tank rifle, adding bases and a 10X Unertl scope. Firing standard ball ammunition, his single-shot .50 produced unimpressive 80" groups at 1,000 yards (eight m.o.a.), but his experiments were an important step toward today’s heavy precision rifles. Brophy later served on the NRA Board of Directors. His PTRD rifle is today displayed at the NRA’s National Firearms Museum.

Chinese and North Korean Snipers

The Communist Bloc’s ubiquitous sniper rifle, the Mosin-Nagant M91/30 rifle and its 3.5X PU scope, saw extensive service with the Chinese People’s Army in Korea but limited use by the North Koreans.

Unlike American snipers, the Chinese normally operated as individual shooters, not as two-man teams. Their most basic tactic was sniping in daylight from dug-in positions. To lure American fire, enemy snipers sometimes placed straw human dummies in elaborate fake positions, alert to any unwary G.I. ready to chance a shot.

Chinese snipers loved their shovels, spending untold hours digging in, often tunneling completely through ridgelines to create excellent concealment and overhead protection from artillery and air attacks. These “volunteer snipers,” a post-war Chinese brochure reports, “backed into tunnels,” only to re-appear and, “inflict great loss on the enemy.” According to Chinese sources, 22-year-old Zhang Taofang was the People’s Army’s top Korean War sniper, and it’s claimed he killed or wounded 214 “American enemies” in 32 days, firing only 432 shots. Assuming eight-hour shooting days, this means Taofang inflicted one American casualty every 63 minutes, every day, for four weeks—and expended only two rounds per hit—a statistic that is difficult to believe.

One of China’s most distinguished movie directors, Zhang Yimou (nominated three times for the U.S. Academy Award) is producing a major motion picture based upon Taofang’s wartime exploits. Announced last fall, “The Coldest Gun” is fully financed, with production commencing in 2021. The film’s producer, Tan Fei, believes the film will send a message, that, “… although the U.S. is strong, it is not unbeatable.”