The first time I saw the 6 mm Creedmoor we were filming a segment for a television show. The rifle, a Ruger Precision Rifle (RPR), wasn’t sighted in—and we didn’t have much ammunition. Honestly, TV is what it is—it’s not always necessary to actually hit anything. But I was curious. So I rough-zeroed the rifle—with as few rounds as possible—and lay prone with an attached bipod. Good Lord, five shots went well under an inch, and recoil in that heavy RPR was so mild that I could call the hits through the scope.

I don’t want to sound like a curmudgeon, but I’m one of the guys who often thinks we have enough cartridges, so I don’t always herald the introduction of a brand-new whiz-bang with glee and anticipation. But there is always room for good cartridges, so while the limited 6 mm world suggests obvious reservations, my first experience with the 6 mm Creedmoor was extremely positive—and I accepted this assignment without reservations.

NECKING DOWN A CHAMPION

In just the past couple of years, Hornady’s 6.5 mm Creedmoor has become extremely popular (September 2017, p. 56), but its 6.5-mm (0.264") bullet diameter has a poor track record of acceptance in the United States. The .264 Win. Mag. made a significant blip when first introduced (1958), but peaked quickly and has fizzled ever since. The 6.5 mm Rem. Mag. (1966) never went anywhere, and, despite amazing initial hype, the .260 Rem. (1996) has been slow. Norma’s 6.5 mm-284 has some traction, and the 6.5x55 mm Swedish Mauser is a great old-timer that refuses to go away—but it’s a stretch to say that any of these 6.5-mm cartridges are “popular.”

Yet amazingly, right now the 6.5 mm Creedmoor is probably the most talked about and most popular cartridge in American riflery. I used the word “amazingly” because the 6.5 mm Creedmoor is not new. It’s been around for 11 years, got off to a slow start, and has suddenly taken off like a rocket. Its hallmarks are accuracy and efficiency—great performance with modest recoil. It uses a .308 Win. case shortened to 1.920" (technically, the .30 T/C case necked down) to reduce the powder column and increase efficiency. This also allows the use of extra-long bullets with high ballistic coefficients (BC) in short actions, without having to seat them so deeply as to intrude into the propellant space.

Given the checkered history of the 6.5-mm cartridge category, only time will tell if it remains popular. But it’s almost inevitable that the latest stubby case with the now-famous name will be necked this way and that. In fact, wildcatters have undoubtedly already taken the Creedmoor case up and down, although what we’re concerned with here is the first commercial cartridge based on the 6.5 mm Creedmoor: Hornady’s brand-new 6 mm Creedmoor. And since the availability of such a cartridge without rifles to fire it is pointless, Ruger has joined in on the introduction, initially chambering both the RPR and the Predator version of the Ruger American Rifle in 6 mm Creedmoor.

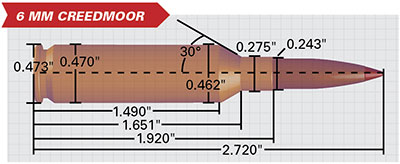

The cartridge is not complicated to create; it’s a simple necking down of the 6.5 mm Creedmoor case to take a 6-mm (0.243") bullet. Someone, however, had to do it first. Simultaneous developments are always possible, but so far as is known, the 6 mm Creedmoor was developed by George Gardner of GA Precision and John Snow of Outdoor Life—both Hornady and Ruger credit them. Especially considering the few (if any) genuine gaps that remain in the broad spectrum of commercial cartridges, wildcatting today requires a reach of faith—so I applaud Gardner, who I don’t know, and Snow, who is a friend, for calling their cartridge the 6 mm Creedmoor, which we can all relate to, rather than succumbing to the temptation of calling it the .243 GS or 6 mm Gardner-Snow, which would have meant much less to most of us.

BRAVE OR FOOLISH?

Even if it is not the name that comes to mind first, you must admit that Hornady Mfg. is incredibly adaptable, agile and innovative. When Gardner and Snow presented their concept to the company, it jumped on the idea—although acceptance in Grand Island wasn’t universal, and some might characterize the move as having jumped on a live hand grenade of sorts. There were obvious reservations considering several existing cartridges. The 6-mm cartridge world is limited, and the .243 Win. is dominant, seemingly almost unshakeable and unimpeachable. I’ve long believed that the 6 mm Rem. is a “better” cartridge—but it has never had a chance. Without question the .243 WSSM was faster, although it essentially died in infancy. And the .240 Wby. Mag. hangs on as a proprietary cartridge, even though it isn’t among Weatherby’s best sellers. The 6 mm Creedmoor, thus, steps into a limited niche dominated by the .243 Win.

It would be silly not to recognize that the .243 Win. is a great cartridge. Since its introduction in 1955, generations of beginning hunters—including yours truly—took their first big game with a .243 Win. It remains a crossover varmint and/or big-game cartridge with a track record for exceptional accuracy. And of course, since the cartridge is so popular, everybody loads for it.

A BETTER MOUSETRAP?

The 6 mm Creedmoor thus enters the 6-mm world bucking some serious competition. I am not going to suggest it will soon take over as the most popular 6-mm cartridge. In fact, I think that’s highly unlikely. However, although I’ve long appreciated the cartridge’s worth, I would never have predicted the recent (and stunning) success of the 6.5 mm Creedmoor either—so who knows?

Today we know a lot more about cartridge case design than we did in 1955, and with the current fascination for shooting at longer ranges, we have a better appreciation for bullet aerodynamics. The 6.5 mm Creedmoor case was designed for long-range accuracy, the intent being to start a long, heavy-for-caliber, aerodynamic bullet at enough velocity that it remains supersonic well beyond 1,000 yds. This principle applies to the 6 mm Creedmoor as well; Hornady’s initial offering is an ELD-Match load with a 108-gr. bullet that has an amazing BC of 0.536 (G1). Obviously that’s a very heavy 6-mm bullet, but that’s also the beauty of the Creedmoor’s relatively short case: Longer bullets, such as this 108-grainer, still result in a cartridge overall length that functions properly in short actions.

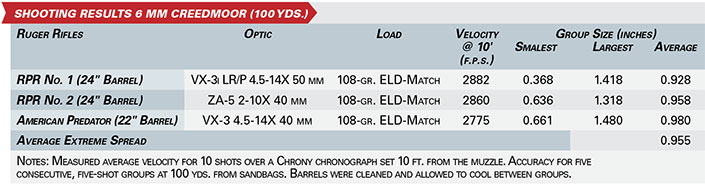

Now, to be clear, we Americans demand accuracy; but, historically, we also crave velocity. The Creedmoor concept is about accuracy and efficiency, but not necessarily maximum velocity. Hornady’s specifications for the 108-gr. match load calls for 2960 f.p.s. from a 24" barrel. For this article I was able to spend time with three 6 mm Creedmoor rifles, two RPRs (24" barrel) and one Predator (22" barrel). Hornady’s 108-gr. ELD-Match was the only load available for testing. At the time this was written, that ammunition was very much a “first batch,” but, as the table shows, all three rifles ran a bit slow. As an average over my chronograph, neither 24"-barreled RPR reached 2900 f.p.s., and with 2" less barrel, the Predator rifle came in at 2775 f.p.s.

Standard velocity for a .243 Win. with a 100-gr. bullet is 2950 f.p.s. Obviously you can play with bullet weights and handloading recipes, and there are extra-fast factory loads such as Hornady’s Superformance. But, just to keep things in perspective, on the same day I also ran some standard Winchester 100-gr., .243 Win. ammunition over the chronograph with my 22"-barrel Ruger American. Uh, yep, that was also slow in that rifle, actual speed 2745 f.p.s. So in terms of actual velocity, I’m not sure there’s going to be a clear winner between the .243 Win. and 6 mm Creedmoor. Theoretically, the .243 has a bit more case capacity and should be a wee bit faster—but in practical terms it’s going to depend on which loads are used. Either way it breaks, the difference isn’t going to be significant.

SHOOTING FOR GROUPS

As we all know, the .243 Win. is no slouch in the accuracy department. The 6 mm Creedmoor has some advantages, not only in case design, but also in its initial introduction with a match-grade load. But barrel quality is such a huge factor in accuracy that I didn’t see any utility in attempting a shootout between the 6 mm Creedmoor and the .243 Win. Over time—thousands of rifles, millions of cartridges—we will learn if the upstart 6 mm Creedmoor will, on average, exceed the accuracy not only of the .243 Win., but also its parent, the 6.5 mm Creedmoor.

I used four rifles in the accuracy testing. As mentioned, I had two identical Ruger Precision Rifles. The first was topped with a new Leupold VX3i LR/P 4.5-14X 50 mm; to keep myself straight I dubbed this “RPR No. 1.” The second was topped with a Minox ZA-5 2-10X 50 mm scope, dubbed “RPR No. 2.” Both were set in Leupold Tactical mounts, using the RPR’s Picatinny rail. The Ruger American Predator in 6 mm Creedmoor was mounted with a VX-3 4.5-14X 40 mm scope using Weaver bases on the American’s rail. Then, just for fun (and curiosity), I took an identical RPR in 6.5 mm Creedmoor and mounted it with an identical VX-3i LR/P 4.5-14X 50 mm scope. Although not included in the accuracy table (after all, this story is about the 6 mm Creedmoor, not its parent cartridge) an obvious comparison many will want to make is exactly how the 6 mm Creedmoor stacks up against its daddy.

So, let’s talk about shooting groups. American Rifleman’s protocol for accuracy is the average of five, five-shot groups. This is a tough protocol, but I am extremely pleased to report that all three 6 mm Creedmoor rifles held a sub-minute-of-angle (m.o.a.) average for five, five-shot groups. Other than scoping, zeroing and chronographing, that’s straight out of the box with a brand-new factory load. Strong!

Hey, we know that the Ruger Precision Rifle is a wonderfully accurate platform, as is the Ruger American. But gun weight is a factor for bench shooting, and barrel stiffness matters more with five-shot strings. For interest’s sake, I cleaned each barrel after each group, and all groups were fired from cold barrels. Optics are also a factor in shooting groups. I fully expected RPR No. 1, with the new, bright, 30-mm-tube VX-3i LR/P to turn in the best performance, and it did with a 0.928" average. But with less magnification (thus more human error) RPR No. 2 held up extremely well with a 0.958" average.

When planning this shooting marathon I asked Ruger’s Mark Gurney, “So, how would you feel if the sporter-weight Predator beat the RPRs?” That was mostly in jest. I didn’t expect it to, and it didn’t. But, geez, it came in pretty close with an average of 0.980"! For three brand-new production rifles with a brand-new cartridge and a brand-new factory load that is awesome performance. Or at least I think it is; you can be the judge.

Now, for my just-for-fun comparison, what about the RPR in 6.5 mm Creedmoor with a big VX-3i LR/P scope (identical to 6-mm RPR No. 1)? Shooting tests are not scientific, but if they were you would call this the “control.” Shooting a similar load, Hornady’s Match line with 140-gr. ELD-Match bullets, I expected it to come out ahead. After all, the 6 mm is brand new, while the parent 6.5 mm Creedmoor has had a decade of fine-tuning. It did, but not by that much. The average of five, five-shot groups was 0.847". If you like numbers, that’s just 0.081" difference between the identically scoped 6.5-mm RPR and 6-mm RPR No. 1.

One of the problems with any test protocol is that groups can be flukes, and flukes can be good or bad, which is why we take an average of several. I caught a calm day and really took my time, I did not see any “called fliers,” but, shooting from a bench rather than a machine rest, it’s impossible to rule out human error (which is also why we take an average). So, interestingly, the very best group out of 20 groups (four rifles, five groups each) was a circular 0.368" cluster from 6-mm RPR No. 1. The next tightest group, 0.584", came from the 6.5-mm RPR. The big difference in the averages, however, was that the worst group (of five) in the 6.5-mm RPR was just over an inch (1.042"). With all three 6-mm rifles I had one group of the five that opened up from 1.3" to almost 1.5". Obviously that skews the average, but it’s impossible to know if it was the fault of the rifle, the load or (most likely) the shooter.

Let’s note, too, that none of these barrels was broken-in, and there was only one production load available. You can explain it any way you wish, but I wasn’t surprised that the 6.5 mm Creedmoor came in slightly ahead—but it should be obvious that the 6 mm Creedmoor maintains an exceptional potential for accuracy.

WHERE DOES IT FIT?

One of the strengths of the 6.5 mm Creedmoor is, when mated with aerodynamic bullets, it remains supersonic for a great distance without beating up the shooter. The 6 mm Creedmoor, when mated with an aerodynamic bullet, also offers exceptional performance—but there is a difference. The 140-gr. 6.5 mm ELD-Match bullet that I grouped in the 6.5 mm Creedmoor RPR has BCs of 0.620 (G1) and 0.312 (G7). This is not even the most aerodynamic 6.5-mm bullet available, but no 6-mm bullet can compete with these numbers. The 108-gr. 6 mm ELD-Match bullet used for these tests is near the top of the 6-mm heap with BCs of 0.536 (G1) and 0.270 (G7). With the muzzle velocities obtained in my testing it will remain supersonic to well beyond 1,000 yds., but it cannot hold up as well as an aerodynamic 6.5-mm at extremely long range.

I just crunched some numbers through Hornady’s 4 DOF online ballistics calculator (hornady.com). The new 6 mm Creedmoor is faster than its big brother. At the actual velocities I was getting—let’s say 2860 f.p.s.—at sea level with a 100-yd. zero the 108-gr. ELD-Match 6-mm bullet drops 312" at 1,000 yds. and retains a very respectable 1368 f.p.s. The 6.5 mm Creedmoor’s 140-gr. ELD-Match bullet, at the stated velocity of 2710 f.p.s., using the same criteria, has 7" more drop at 1,000 yds. but has a retained velocity of 1419 f.p.s., meaning it will pass the 6-mm bullet based on pure aerodynamics. If one were to start the same 6.5-mm bullet at the same velocity—2860 f.p.s. (not likely in the Creedmoor case, but easy in larger cases)—then you’d have 32" less drop at 1,000 yds. and a retained velocity of 1546 f.p.s.

Ultimately, a higher BC eventually wins—but that’s accepted and is not what the 6 mm Creedmoor is about. Instead, it offers incredible capability for a 6 mm. “Long range” means different things to different folks, and not everybody needs maximum extreme-range capability. The 6.5 mm Creedmoor is a mild-mannered cartridge, but the 6 mm Creedmoor is a lot more fun to shoot. With a fairly heavy rifle like the RPR you can, essentially, call your shots through the scope, and with the much lighter Predator there is still very little movement from recoil. It thus combines proven Creedmoor-case accuracy with even more manageability—and the ability to use the longest and most aerodynamic bullets in a short action designed for the .308 family’s cartridge overall length.

The 6 mm Creedmoor comes to market against stiff competition, but I think it deserves success. Whether you’re into tight groups or ringing steel, it has plenty of long-range capability. It’s going to be an awesome varmint and predator cartridge, and will fill the same crossover role in regards to big game as its competitors.

Now we’ll see what the shooting public thinks.