This article was first published in American Rifleman, October 1945

By Lt. Comdr. William J. Thompson

When the U.S. Marines stormed ashore at Iwo Jima, the Seabees swarmed in with them, armed and ready to fight, if needed.

In the early days of the assault there was no opportunity for the Seabees to fight. They were too busy handling materials, supplying the men on the line, and doing whatever construction could be done under fire. For, although they hadn't time to shoot back, they were shot at. Mortar shells and small-arms fire rained incessantly on the beachhead area.

One tired and dirty-faced Seabee crouched in a shell crater when a mortar barrage let go. “If we could only fight back it wouldn't be so bad,” he said. “It drives a man mad to wait and wait, never knowing where to expect the next shell."

As the fierce fighting left the beaches and Motoyama airfield was wrested from the Japs, the Seabees moved in behind the lines. Frequently they had to move their bulldozers and earthmoving equipment from the area because of enemy fire. No place was secure. They worked—and took it.

But they got their chances at the Japanese after the battle lines were pushed back far from their construction projects, that is, as far as they could be on an island that was only five miles long and about half as wide. It was then that the Seabees showed they could shoot! Tactics reminiscent of Indian-fighting days were brought into use. The men went to work in the inevitable green uniform, wearing helmets and carrying carbines and other weapons. On every project “Up North,” as the boys termed the central portion of the island, it was necessary to post sharpshooting guards. The survey crews kept an armed guard with the transitman and each rodman. The M1 carbine was a favorite weapon because of its portability, fire power, and effectiveness at the short ranges at which the enemy was encountered.

Bulldozers were busy pushing the rough terrain into usable areas. Suitable space was needed for air strips, for camps, and for roads. Sentinels were stationed at vantage points to protect the equipment operators, the oilers, and the other men in the work details.

The Japanese that had not been killed when the Marines mopped up the last pockets of resistance, crawled into the maze of tunnels and caves that hollowed the central and northern portions of the island. From the caves they fought with fanatical fervor and with the finesse of an intelligent enemy. The terrain favored their passive defense. The need for water and food brought nocturnal forays that kept the camp guards busy.

One night, long after “D” Day, Seabees spotted a thin veil of steam coming out of a cave less than 100 yards from two battalion guard posts. A few minutes later, a trip flare was kicked off and there were the Japs. Instantly, a hail of Seabee fire was directed at the cave dwellers.

“I grabbed a tommy gun and started spraying the hillside,” said Calvin E. Broady, Seaman First Class, of Berea, Ohio. “Those [guys] began ducking behind rocks or anything else they could find.” Norman L. Baker, Carpenter's Mate Third Class, of Walled Lake, Michigan, was in the guard Post adjacent to Broady. “The first thing I knew was the flare going off and Broady yelling, ‘There's one over there, and another one and another one—Christ, there must be a thousand of ‘em. It sounded like 'D' Day all over again,” added Baker. “My gun jammed and I was really scared. I didn't waste any time tradin’ it. One Jap had almost reached the dugout when I got him.”

“When the shooting started I joined in with an M1 (Garand),” said Russell J. Mellinger, Carpenter's Mate Third Class, of Indianapolis, Indiana. “After the flares burned out the Sergeant of the Guard came up behind the dugout and fired some parachute flares they call ‘Bouncing Betties.’ We saw a [guy] try to hide in an oil barrel that had the head knocked out of it. Next morning we examined the barrel and it was a sieve. So was the Jap.”

When daylight came, the Seabees discovered eleven Japanese before their posts. Ten had fallen before the deadly fusillade and the eleventh had successfully escaped the scathing fire by hiding in a hole. Total count-ten killed, one prisoner, three escaped.

Apparently the Japanese had not realized that, on opening the entrance to the cave, steam came seeping out of the hot ground.

It gave them away before the flares were tripped. Some of the caves become unbearably hot from the underground temperatures when the entrance is closed. Upon opening a cave, or during rainy weather, they frequently emit steam. This time, nature was on the side of the Seabees. “We had some interesting evenings at that post besides that night,” said Robert S. Humphrey, Coxswain, of Lexington, Kentucky, “but it was usually one or two instead of a dozen. There were a few times I was glad I had learned to shoot bull's-eyes.”

Marines were still patrolling a section where one of the construction battalions was busy building the battalion camp. Someone suggested that the battlewise Marines divide their nightly ambushes and guard posts with Seabee camp outposts. This was done. After three or four nights, in which combined efforts netted several dead Japanese, the Seabees were on their own. The coaching and seasoning were excellent, for the Seabees soon performed like veterans. Getting a Japanese was almost a nightly occurrence. The posts were manned on a volunteer basis and soon the battalion commander was besieged with requests to do guard duty at the new camp site.

“One night we put an ambush on top of a high rock near the battalion water point,” Robert P. Hopkins, Carpenter's Mate Second Class, of Oakland, California, said. “There were three of us in the ambush and it was my turn on watch. I saw three Japs in the moonlight, creeping toward the rock. I pointed them out to my two companions and then fired a burst with a tommy gun. Two of the Japs were knocked down. The next morning we found we had killed two, the other one had escaped.”

“One of the funny things that happened that night was the new youngster we had with us,” added Fred G. Fogg, Shipfitter Second Class, of Pacific Grove, California. “He manned the .30 caliber machine gun. When the firing started, he yanked back on the trigger and the next thing Hopkins and I knew he was firing at an elevation that would make you think we were having an air raid.”

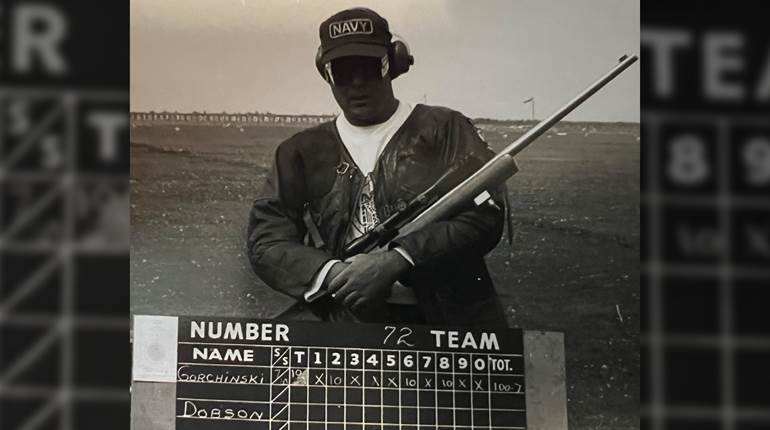

Hopkins is a thirty-year-old ex-Texan who really knows how to handle a gun. In boot camp he fired a heartbreaking 174 x 200 score for record with the M1 carbine—just one point short of the necessary score for the Navy's Expert Rifleman Medal. A year later, before shoving off for this operation, he tried for record again and ended up with 182 points to earn the coveted medal with a wide margin.

“We killed several Japanese from our guard posts while building the camp,” Hopkins added, “but the biggest thrill was capturing twelve prisoners. It was about half an hour after daylight. The Marines had secured their posts and left for chow. We were getting ready to return to our bivouac for breakfast when I saw a movement behind a rock. I fired a quick shot but didn't connect. A minute or so later a white flag was stuck up over the crest of the ridge. We flanked the ridge with another group of guards and asked for the flag waver to come out. The flag-bearer came out, followed by others in single file. We made them take off all their clothes so they couldn't hide hand grenades. Next we searched their clothing and then let them dress before we loaded them on the truck.

The driver took us by the Marine bivouac so we could show them what they had missed. The Marines looked at us with amazement. One of the veterans said, "Hell, you Seabees don't need us around anymore!”

Surveying roads, camp boundaries, and pipe lines brought the most opportunities for contact with the enemy. Each rock, each gully or draw, each cave opening was a potential hiding place for a Jap.

One construction battalion camp is named in honor of a member of their survey crew killed while running the traverse for their camp site. Lieutenant (jg) Hiram H. “Fuzzy” Farnsworth, Civil Engineer Corps, U. S. Naval Reserve, of Las Cruces, New Mexico, was in charge of the party. On that particular day, Farnsworth demonstrated that his Expert score with the carbine and the two Sharpshooter qualifications with the Springfield and .45 caliber pistol were no fakes.

“We were running a traverse control that crossed deep ravines, which were full of brush and caves. All morning we had struggled through and over this type of terrain. We were on the alert and kept two men as lookouts on each side of the line. Also, we had one guard follow about fifteen yards behind the crew so that we would not be attacked from the rear,” said Farnsworth, describing the area he was working.

“About three o'clock in the afternoon we were moving up to a new transit point when I heard an explosion behind me and to my left. I whirled, thinking that one of the men had stepped on a mine. Instead, one of the men had been hit by a hand grenade thrown from a slit trench in a draw. A Jap moved in the trench and I fired two shots into his head with my carbine. At the same time another started running down the draw. I knocked him down. At that moment two hand grenades were thrown toward me by three Japanese farther down the ravine. I ducked from the grenades and emptied my clip through the brush at them. That ended the fight. When it was all over, I found that it lasted only about ten or fifteen seconds.”

Edwin A. Mullin, Carpenter's Mate First Class, of New Castle, Wyoming, from another battalion, had a similar experience as chief of a survey party. Mullin isn’t a gun nut but he has hunted coyotes, deer, and antelope on his father’s ranch. When he went through boot camp, he qualified as a Sharpshooter with the carbine. He’s the kind of fellow that’s more interested in classical music than in shooting, but his ability to handle a carbine paid dividends on this particular day.

“The transitman had moved up to a point on a ridge and was getting the transit leveled. I was copying some notes,” said Mullin. “One of the guards was scanning the countryside when he saw the officer in charge of the survey parties coming down the ridge. The guard turned and found the transitman standing motionless by the instrument.”

“Get on the ball, the boss is coming,” said the guard. “Let's look like we're at work.” The transitman lost his paralysis and pointed toward some rocks about fifty feet away.

“’There's a Jap down there!’ he stammered. We hit the dirt and I began stalking those rocks like I was after an antelope. Pretty soon I had a good view of the spot and I waited for the Japanese. A minute or so passed and I saw the top of a brown cap slowly raising above the top of a rock. He didn't have on a helmet. I didn't wait for him to expose his entire head. I fired. At the crack of the carbine he disappeared. We waited awhile and nothing happened, so I sent two guards to flank the draw. They found him. He was harmless even if he did clutch a grenade in his hand. The bullet from my carbine plugged him in the forehead right at the hair line.”

There was one organized banzai attack after Iwo was secured. The path of the attack stopped at the edge of camp where a battalion, which had just reached the island, was bivouacked. For two or three hours it was a real initiation for the newcomers.

“It was hardly daylight when the charge started,” said Richard C. Webster, Carpenter's Mate Second Class, of Crewe, Virginia. “I was on watch and, the first thing I knew, there was shooting all around me. It was being done by some Marines waiting to go aboard ship, and by some Army groups. I did a lot of shooting too. When it was all over, there were ten dead Japanese in one shell hole not far from my post.”

Seabees are more noted for their building than for their shooting, but they do some of both. One enterprising ‘Bee mounted a light machine gun in the body of a dump truck. He jockeyed the truck around where he had a good view of the area for frontal fire. For two or three nights he found enough targets to keep his interest but, as the Japanese thinned out, he let boys in their dugout guard posts take over. Perhaps the Japanese became suspicious of the vehicle.

On Iwo Jima, the Seabees did more than build bases en route to Tokyo. They demonstrated they could protect themselves, or fight if needed, as well as construct airfields. And they used all of the various types of small arms a construction battalion carries. The total Japanese killed and captured makes a fancy figure for a service troop organization. Especially one that did not go looking for the enemy.

They are a versatile organization. They are sharpshooters with carbines, Thompson submachine guns, and machine guns, as well as experts with their famous bulldozers. On Iwo Jima they proved that “Seabees Can Shoot!” as well as build.