This article, "Ruger's New Vaquero: Made For The Cowboy," appeared originally in the November 2005 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

Bill Ruger’s bread ’n butter gun was unquestionably his first—the .22 Auto. But he sensed something significant in the American shooter’s psyche when he came out with his first single-action revolvers in .22 Long Rifle at a time when Americans were captivated by the colorful history of the Frontier era. Ruger’s Single Sixes were instant hits, so the astute Bill Ruger immediately followed with a center-fire revolver called the Blackhawk. Once again, he had a hit, and his company was off and running. Within a few years, Ruger’s modernized single-actions had established a niche for themselves on practical grounds. A related niche is now filled with the New Model Vaquero, the subject of this story. Fully understanding both the niche and the gun requires taking a little time with some history.

Blackhawks quickly earned a reputation for being tougher than Arizona antelope jerky. Instead of educated Kentucky windage, the old Model Blackhawk buyer had a decent-quality adjustable rear sight. He also got a brute-strong grip frame and investment-cast mainframe, and modern high-quality springs, pins and screws throughout. Blackhawk price tags were easy on a working stiff, too. Ruger literally brought the single-action revolver into the 20th century.

In 1973, Ruger completely changed the lockwork of the Blackhawk revolver and went to a somewhat larger frame and cylinder. These guns are referred to as New Models. They have been with us for 32 years with an enormous array of variations in chamberings, sights, finishes and barrel lengths. Lots of shooters went for the Bisley-style grip frame that came along in 1986 and offered arguably better recoil control in the more powerful chamberings. But the gun that came along in 1993 is really more germane to our story.

It was the Ruger Vaquero, a New Model Blackhawk variant that came with fixed service sights and a simulated case-hardened main frame on its carbon steel variations. The company developed the model in response to a demand not far removed from the one that drove the first Ruger single-actions into existence in the early 1950s.

Cowboy Action Shooting (CAS) burst onto the shooting scene in the mid-1980s and grew by leaps and bounds. This was a tradition-based sport, and everyone wanted to use guns that looked like the arms of the frontier era. Therefore, the original Vaquero—essentially a fixed-sight variant of the New Model Blachawk—was an instant hit.

Some CAS shooters have been reluctant to use original Vaqueros because of their size and weight. They are pretty hefty revolvers, but that’s because they were specifically built for strength.

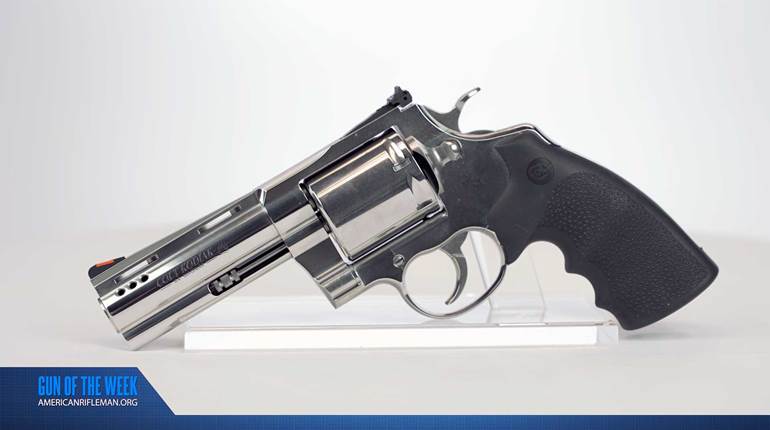

The XR-3 Vaquero (above), shown here next to a replica Peacemaker from Cimarron (top), demonstrates that the new Ruger looks and balances much more like the original Single Action Army.

Now, for the 21st century cowboy action shooter, Ruger offers the New Vaquero. The main difference in the two Ruger Vaqueros is size. The New Vaquero returns to the smaller “XR-3” grip frame of the 1950s-era Blackhawks. Further, the main frame is also smaller, with a significant reduction in the size of the cylinder itself. It’s as though Ruger went back in time and built its original gun, except with fixed sights. Compared to the first-style Vaquero, the New Vaquero has the weight, balance and most of the features of the 1873 Colt product it emulates.

New Vaqueros are made in Ruger’s three principal barrel lengths: 7½", 5½" and 4 5⁄8". Two calibers are available: .357 Mag. and .45 Colt. Your new Vaquero can be either a blue and casehardened gun in the old style or all stainless steel, polished to give the appearance of nickel plating.

My specimen was the gun that is likely to be the most popular—a 4 5⁄8" .45 Colt in the blue and casehardened finish.

When Ruger changed from the original Blackhawk revolvers to the New Model Blackhawks in 1973, there were two major differences. One of them was the overall size, which we have already talked about. The other change was in the gun’s lockwork. For a variety of reasons, Ruger decided to discontinue the original actions, which handled almost exactly like the original Colt. These pre-’73 guns had three visible screws on the frame and shooters began to refer to them that way—“three-screw Rugers.”

All post ’73 guns—including the New Vaqueros—have a pair of pins. It is a quick means of identifying the gun without picking it up. By now, most single-action shooters are aware that the original action can be unforgiving when mishandled. Ruger even went so far as to develop a retrofit action, which it will install free of charge in the pre-’73 revolvers. If a shooter should be so unwise as to load all six chambers of a pre-’73 Ruger and so clumsy as to drop the gun on the hammer, it may fire. Every savvy sixgunner understood that, for all practical purposes, his six-gun was really a “five-gun.” Not so with all of the post-’73 Ruger single-actions, including the New Vaquero.

Looking at the New Vaquero (l.) as compared to an original Vaquero (r.), you can see there is a large and immediately noticeable difference in the size of the cylinder and frame. Although it has smaller frame and cylinder dimensions, the New Vaquero is proofed with the same loads as the original gun.

The loading procedure for this gun is simple. Open the loading gate on the right recoil shield. This will permit the cylinder to turn freely. Slip a cartridge into the visible chamber, then rotate the cylinder clockwise until you hear a click. Insert another round and repeat until the gun is full. CAS shooters who are required to load five by match rules simply load five and stop. There’s no more of the old “load one, skip one, load four” stuff. Five straight will leave the empty chamber under the hammer and give a competitor five consecutive shots. For any other use, there is no need to leave the chamber empty. Actually, there has not been such a need on new Rugers since 1973.

In order to make speed handling of the revolver a little easier, the New Vaquero comes with a new part that Ruger calls “a reverse-indexing pawl.” The audible click I mentioned simply tells the shooter the cylinder is precisely aligned with the loading-gate cutout in the frame. It’s also aligned with the traditional spring-loaded ejector rod in its housing on the right underside of the barrel. This arrangement makes the New Vaquero a very simple and safe single-action revolver to handle and fire.

Subjectively, Ruger has added some other handling improvements. The hammer spring is redesigned for smooth and easy cocking. A new shape gives the hammer a slightly longer spur and a somewhat different down curve to the top edge. This makes the gun look a little more original, but it also means the shooter has increased leverage. Older Frontier Models had a so-called “blackpowder chamfer” on the front edge of the cylinder. So does the new Vaquero, and among other things, it speeds up holstering and is easy on the leather.

The butt shape of the new Vaquero is the XR-3 style used on original Blackhawks. It closely replicates that of the original Peacemaker. The checkered stocks are plastic, but they strongly resemble the hard rubber ones used by Colt in the 1880s.

I put an older Vaquero next to the New Vaquero. Apart, the two guns look quite a bit alike. But on close comparison, the differences are clear. The first-issue Vaquero has a cylinder that measures 1.73" in diameter. The New Vaquero cylinder has a 1.67" cylinder. Cylinder length is 1.70" for the original Vaquero, as opposed to 1.61" for the new one. The frame of each model is scaled to match the cylinder, so the New Vaquero is slimmer than the original. The composite grips are slimmer and seem a fraction lighter. When compared to a Peacemaker, the Vaquero seems to have a slightly larger trigger guard and trigger.

Many Ruger shooters roll their own loads and work from loading manuals that list Ruger .45 Colt loads separately from those intended for other single-action revolvers. This Ruger .45 Colt revolver has a cylinder that is measurably smaller than those of the previous models. Will it take those more powerful handloads? When I asked, I was told that the New Vaquero was proofed with the same loads as the previous Vaquero. I was also told that Ruger would not guarantee this or any other firearm with handloads—would you logically expect it to do so? Ruger works mighty hard to build strong, safe guns that will last for many thousands of rounds, so use this one with sensible ammunition, and you will end up giving a still-working revolver to your grandchildren when you head for the big corral in the sky.

I tried the sample gun with a couple of commercial .45 Colt loads. The results are tabulated on p. 78 and show a revolver that shoots quite respectably. I also took on a few dirt clods and my soda can after lunch. The handling, in terms of pointing, cocking and shooting, is better than any Ruger single-action I can recall. Clearly, this is a thoroughly modern rendering of a dated revolver type. Ruger’s designers have expended no small effort to make the Vaquero as easy to use as they possibly could. At the same time, they kept the spirit and style of the design as historically pure as possible.

Rugers have always been known for their rugged dependability. There’s nothing I see here that is contrary to that reputation. I believe the Ruger New Vaquero will be the dominant revolver in CAS in short order.