This review of the Remington 105 CTi, "A 21st Century Shotgun," appeared originally as a feature in the December 2006 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page here and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

It’s easy to say a new gun is revolutionary. It’s harder to prove it. With its 105 CTi, Remington has brought a host of innovations to the semi-automatic shotgun. The first has to do with materials. The CTi’s receiver is of investment-cast titanium—thus, the “Ti” in the name. Of course, Ti is the symbol for titanium on the periodic table of elements. Titanium’s weight is 40 percent of a comparable piece of steel, yet the yield strength of the heat-treated receiver is four times higher. It’s the first shotgun to include carbon fiber in its receiver construction, explaining the “C.” It’s the first production bottom-loading and -ejecting autoloader from a major American manufacturer. The 105 CTi also has a built-in recoil-reduction system and an innovative trigger and loading system.

The intended year of introduction was to be 2005 for the 105 CTi, a century after the John Browning-designed Remington Autoloading shotgun was announced. It took Remington’s engineers a little longer than they anticipated to get the 105 CTi to market, and I didn’t receive a production sample until August 2006. But that’s okay, as the gun was well worth the wait. I am one of Remington’s biggest fans and, at the same time, one of its harshest critics. I expect a lot from America’s oldest gunmaker. The Remington 504 and 597 rimfire rifles earned very high marks from me, but I still shake my head in befuddlement over guns like the 722 Viper and the Model 700 Etronix rifle. The latter, offered from 1999 until 2003, is likely one of the most innovative firearms of all time, but answered a question consumers never asked.

The 105 CTi’s receiver, which mimics the external dimensions of a Model 1100, is skeletonized at its top to reduce weight and material cost. It is what Remington calls a “sourced” part, as the firm lacks the tooling to investment cast or machine titanium. Because the bolt locks into a barrel extension, the receiver is a non-stressed part, so removing the material is not a problem. Remington has epoxied a carbon fiber cover over the openings in the receiver’s top. It’s for looks more than anything else.

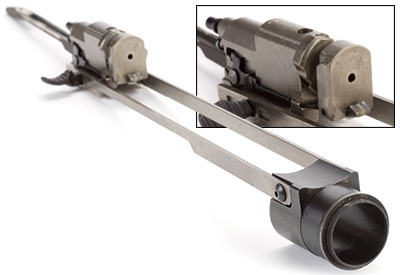

The investment-cast bolt is made of 4140 steel and rests on a bolt slide that rides in dual raceways inside the receiver, and there is a slot cut for the operating handle on the right side. A separate rotating bolt head behind the fixed bolt face rotates 75 degrees for locking and unlocking. The bolt travel is straight back and forth, and the extractor, powered by a mousetrap-style spring, is fixed to the lower front of the bolt face. The extractor doesn’t rotate and stays in-line with the bore. This part has been re-contoured from the pre-production samples I shot in January and now has a radiused top that corresponds to the shape of the cartridge rim. We had some problems with the flat-faced design and some field loads, but the new version worked flawlessly on the production gun.

While the bolt’s locking ring resembles the camming Benelli design, at the front of the magazine tube is a pressure-relief gas-operation system. The gas cylinder is mounted under the barrel, and there are two rear-facing gas ports as well as four smaller holes farther forward. At the front of the gas cylinder is one steel gas-seal ring, while another surrounds the magazine tube atop the action-sleeve assembly. This ring and its assembly are pushed rearward by the bled-off gas, and they are linked to the bolt slide via two stout action bars. The bolt unlocks on its cam track as the action sleeve and carrier moves to the rear. After its full travel, the bolt and action sleeve are pressed forward by a coil recoil spring surrounding the magazine tube between the action sleeve and the front of the receiver.

Available in 26" or 28" lengths, the barrel is overbored to 0.735" (it measured 0.736" on our sample) and has a tapered vent rib made of carbon and aramid fiber epoxied to its top. The rib has a white bead at its front as well as a mid bead. As this is Remington’s first overbored autoloader, familiar RemChokes are not interchangeable with it. Instead, Remington supplies three ProBore choke tubes optimized for use in the 105 CTi. The forcing cones are also lengthened.

The trigger is one of the best I’ve tried. The key is its rolling sear. Instead of having a flat surface on the hammer that engages a flat surface on the sear, the sear is a round, transverse-mounted pin with a corresponding hook on the top rear of the hammer. In short, it’s smooth and crisp. There was a short amount of take-up, followed by a crisp break of 3 lbs., 9 ozs., not varying by more than half an ounce for an average of 10 pulls. While a good trigger may not be as important on a shotgun as on a rifle (slug and turkey guns aside), I’d say this could be a very good rifle trigger.

As a matter of fact, I prodded the company to look into incorporating this design into other guns, such as the Model 597, as I felt it was that good a trigger. The aluminum trigger housing holds all the fire-control parts and is a self-contained unit that may be removed for cleaning or maintenance by simply drifting out two pins. The trigger-blocking crossbolt safety is in the rear of the trigger guard.

Loading and ejection is through the action port in the receiver’s bottom—like an Ithaca Model 37. Unlike the Ithaca, the 105 CTi has a “smart carrier” that is the key to the gun’s TurboFeed system. You can load the gun conventionally by placing a shell in the magazine with the bolt closed, then pull the operating handle rearward and let it go forward. The next option is where the 105 CTi differentiates itself.

If the bolt is open, and no shell is in the magazine, pushing the round just about all the way in—so it engages the two arms of the carrier but is not quite engaged by the magazine stop—then pulling your thumb out of the way allows the round to be lifted into the chamber, and the carrier frees the bolt to travel forward, chambering the round. Then the rest of the rounds are fed conventionally into the magazine. Its description is far more complicated than actually doing it. To be frank, it took some getting used to, but once you get the hang of it, it’s slick. Pressing down on the feed latch on the front right of the action port frees the shells to pop out of the magazine for unloading.

Most Remington autoloaders have the recoil spring at the rear of the bolt as in the 11-87. In the 105 CTi, as mentioned above, the recoil spring surrounds the magazine tube in the Franchi style, and the recess in the buttstock that usually contains the spring houses a new “rate reducer,” which is essentially a hydraulic piston to the rear of the bolt. What would normally be the link protrudes rearward with its tail engaging the cup-shaped top of the recoil reducer.

The oil-filled cylinder will provide more resistance if more energy is forced onto it. A heavier load will increase the reward velocity, but the friction imparted by the oil will increase, as well. Remington engineers claim a 48-percent reduction in recoil, but lacking the means to scientifically measure recoil reduction, I’ll have to take them at their word. I will say follow-up shots are quick, and there is very little muzzle rise, even with 3" high-velocity duck loads.

On a January duck and upland bird hunt at the excellent Deer Creek Lodge in Sebree, Ky., I had the opportunity to try out the 105 CTi. In the hands, it was very lively for a gas-operated, 12-ga. semi-auto. And the weight reduction comes at the receiver with plenty of weight still up front to help the follow through. The gun comes to the shoulder quickly yet swings very well.

Once a production model arrived, I fired 525 rounds of target loads at skeet and five-stand over the course of several days without cleaning and without a hitch. I also mixed up 2¾" and 3" light and heavy loads in the same magazine, and the 105 CTi cycled them all without fail. At the range, follow-up shots were quick, and it was easy to stay on target if a second shot was required.

Best of all, the gun still looks like a Remington. Designers often get tempted to go outside the box on a project like this, but while the construction and design are revolutionary, the lines are pure Remington. Also, for left-handers, there are no shells popping out the right side to distract you. This is as user-friendly an autoloader for southpaws, without being a truly left-hand gun, I’ve seen.

Best of all, the gun still looks like a Remington. Designers often get tempted to go outside the box on a project like this, but while the construction and design are revolutionary, the lines are pure Remington. Also, for left-handers, there are no shells popping out the right side to distract you. This is as user-friendly an autoloader for southpaws, without being a truly left-hand gun, I’ve seen.

Engineers Brent Jarbow, Michael D. Keeney and Director of Development Danny Diaz deserve a solid and sincere pat on the back for the 105 CTi. Remington’s John Fink described the mandate behind this gun as being to create a new shotgun using “cutting-edge technology to see Remington semi-auto shotguns well into the 21st century.” When asked about the 11-87, Fink replied, “We’ll let the market decide.” Indeed it will.

In my view, the 105 CTi is the most innovative gun Big Green has ever produced—and it’s made here by American workers in Remington’s Ilion, N.Y., factory. I would place it ahead of the Model 700 Etronix rifle in innovation—and it’s far more useful to the average shooter.

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=770&height=430&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)

![Auto[47]](/media/121jogez/auto-47.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=150&height=150&rnd=134090788010670000&quality=60)