Want to know the trouble with shotguns?

Pump-Action—You have to shuck the fore-end backward then forward to reload. This while trying to maintain cheek weld, keeping your eye on the target and the gun swinging smoothly.

Autoloader—Yes, it loads itself … most of the time. But 100 percent reliability? We have yet to see that.

Double—C’mon, it holds just two shells; magazine capacity is zero. Good ones cost at least a couple grand and a great one costs as much as a new car.

[He doth protest too much.]

I hear you, Rifleman readers. Of course all three shotgun types are highly functional and universally prized by owners. But the point remains, there’s room for improvement.

And most recently, improvement has come from a source that’s somehow both perfectly logical and yet rather surprising: Remington. A 200-year-old company whose résumé includes the most popular semi-automatic shotgun of all time—the Model 1100; 4+ million sold and counting. But a company reportedly on the skids over the past decade, one whose semi-automatic shotgun credibility and market share have been eroded by imports from Italy, Japan and Turkey.

To battle back, Remington reinvented its gas operation with a system called VersaPort, a concept modeled on one developed in Italy in the 1990s and first adapted by the Benelli M4. After obtaining a U.S. patent, Remington introduced VersaPort in its Versamax model in 2010. For various reasons, the new autoloader was slow to catch on, but as its unconventional operating system earned praise from American Rifleman (December 2010, p. 54) and other shooting-press outlets, this robust successor to Ilion stalwarts such as the Model 1100 and Model 11-87 began to find favor among waterfowlers and 3-gun competitors.

Even so, it wasn’t the right gun to take on today’s top imports, which tend to be lightweight (7¼ lbs. or less), sleek and compact, more reliable than older semi-automatics, and often are equipped with an on-board recoil reducer. Enter the Remington V3 Field Sport, a new gun that ticks all those boxes and more. Thanks to its own rendition of the VersaPort concept and another equally creative mechanical feature, the V3 is forward-thinking even as it strives to exemplify the granddaddy of shotgun-design axioms, the one about keeping the weight between the hands.

Engineering To The Middle

Instead of relying on a gas system rooted near the end of the magazine tube some 7" to 10" in front of the action, the VersaPort centers the entire gas diversion/piston operation directly ahead of the receiver. Its pinhead-size ports are located in the barrel breech, two pairs each at roughly 5 and 7 o’clock. What makes this design truly ingenious is that it relies solely on the chambered shotshell to regulate how much gas is diverted to work the action. With longer, more powerful 3" loads, half the ports are blocked, whereas the shorter and milder 23/4" shells leave all eight ports uncovered. The intention is to equalize the effect of the gas in cycling the action and also to equalize the amount of recoil delivered to the shooter regardless of the load fired.

The ported gas expands into a two-chambered block welded to the underside of the barrel where it imparts force on twin short-stroke pistons. Their high-impulse travel spans just 0.481", enough to unlock the rotating bolt head and shove the heavy bolt rearward with the momentum needed to clear the loading port and eject the spent hull. With this system, there is no need for mechanical adjustments or swapping out springs, valves or O-rings to accommodate different loads.

For consistency with uncharacteristic loads—2 3/4" magnums, for example—the gas block’s cylinders also contain pressure compensating valves that immediately bleed off gas in excess of what is used to cycle the action. Because all the venting occurs in such close proximity to the chamber, Remington says less pressure builds up to be felt as recoil. It’s also quite clean, in part because there’s less surface exposure (than in forward-mounted gas systems) to “catch” the carbon buildup.

But VersaPort is just one way the V3 was engineered to center weight, and, in fact, it’s not the most innovative. The biggest advance is the lack of the customary semi-automatic gun’s recoil spring and tube extending into the buttstock. That beefy appendage—which spreads weight toward the butt—has been replaced with smaller tandem recoil springs located on guide rails along the lower inside receiver walls. Compressed when the pistons retract the action, these springs rebound to bring the bolt and a fresh round into battery.

Remington product managers say the design results in more efficient cycling, fewer maintenance and repair issues and smoother bolt operation. For sure it’s not at all difficult to swab and oil the receiver-mounted recoil springs, an ounce of prevention that beats the alternative of removing a buttstock to gain access to a gunky mess that impedes action cycling, or worse, to a rusted, bent or broken mainspring.

All this—almost all internal parts and the work they do—occurs in a very compact space (remember, between the hands), and in fact the V3 receiver, at 8.36", is one of the shortest in its class and nearly a full inch shorter than Versamax receivers. Literally the only weight not between the hands is in the buttstock, fore-end, barrel and magazine tube and spring.

Built To Perform

Shotgunners who insist that performance completely trumps looks will be the biggest fans of current V3s. While the lines rival the streamlined form of classic Model 1100s, the all-black or camouflage synthetic stocks available thus far are rather plain despite molded-in accents that add some visual flair. A walnut-stocked version is reportedly on the way, and the representative “show” guns we’ve seen were quite nice.

Aesthetics aside, the stock design enhances performance in at least three significant ways. Smartly, it is equipped with Remington’s proprietary SuperCell, perhaps the best factory buttpad going. The strong-hand grip area is generously scalloped to fit nearly the entire lower palm—an aid to handling comfort and control. And the fore-end is very shallow, which closes the gap between the foregrip and the sighting plane, an asset optimized in side-by-sides, though not to that extent here.

The gun’s controls are handy and useful, beginning with its safety button at the rear of the trigger guard, a familiar touchpoint for Remington shooters and instinctive for others. The bolt locks open when retracted, and is released by a contrasting plunger on the right-hand receiver wall. In a new wrinkle for the company, the V3 has a magazine cutoff switch, which is located where the floorplate meets the trigger guard, a nod to both versatility and safety that makes it a snap to unload the chamber without dumping shells remaining in the magazine or to switch loads quickly when the situation warrants.

The gun’s controls are handy and useful, beginning with its safety button at the rear of the trigger guard, a familiar touchpoint for Remington shooters and instinctive for others. The bolt locks open when retracted, and is released by a contrasting plunger on the right-hand receiver wall. In a new wrinkle for the company, the V3 has a magazine cutoff switch, which is located where the floorplate meets the trigger guard, a nod to both versatility and safety that makes it a snap to unload the chamber without dumping shells remaining in the magazine or to switch loads quickly when the situation warrants.

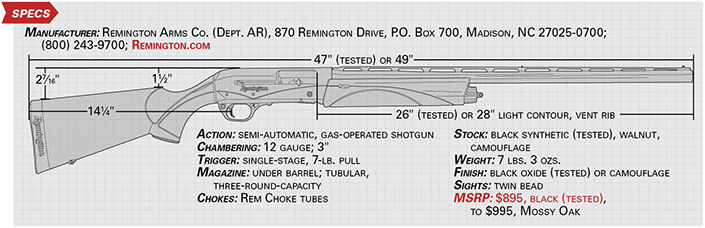

With a 26" barrel, the V3 weighs 7 lbs., 3 ozs., slightly more with the 28" tube. Barrels are topped with a ventilated rib that contains a small mid bead and a larger white bead at the muzzle, which naturally is threaded to accept Rem Chokes. The receiver topstrap is drilled and tapped to facilitate installation of an alternate sight. It’s a bit odd that the receiver and the barrel wear different finishes—both are matte, but the receiver is a bit smoother and darker. The receiver sidewalls are minimally decorated with a flaring chevron and also carry identifying marks, including a fingernail-size QR code.

Shooting and Handling Characteristics

Because the V3 was unveiled to the shooting press in the fall of 2014, more than a year before its actual retail launch, we were able to test more guns and have more NRA editors involved in shooting them than is normally the case. The prolonged T&E, with everything from heavy waterfowl magnums to ultra-mild 2 1/2”, 7/8-oz. spreader loads, afforded ample opportunity to gauge the gun’s functionality. In myriad weather conditions, from guns freshly cleaned to others badly in need of attention, we did not experience a single failure to fire, extract, eject or reload.

One curious trend was that our inexperienced shooters all reported better-than-expected performances with the V3s, whereas veteran shotgunners struggled at first to match their usual scores. It’s worth noting, though, that after a couple boxes of shells, our hit-ability was back to normal. It appeared that beginners were intuitively aided by having more weight centered between the hands, though some work may be required before that advantage carries over to seasoned shotgunners.

My first go with a V3 consisted of about 40 rounds fired at a five-stand course perched atop a steep hillside. The shooting was done from a platform with targets launched below our feet, angling and dropping sharply into thick foliage. My fellow shooters and I had to track and shoot fast, though doing so required little lateral swinging. After striking out on the first half-dozen, I got the timing and went on a couple nice runs where it seemed easy to shoulder the gun, rotate to the flight path and intercept the bird in the narrow window of opportunity. These shots were all about intuitive reflex—point-shoot, break it or miss it. The fact that I was hitting report doubles with my second and third shots indicates that I was recovering form pretty fast, and I’m not so sure that would have been the case with an over-under of similar weight.

Similar learning curves were required when I shot skeet and sporting clays, particularly on crossing targets. In those cases it might have helped to have a gun with a 28" barrel (our loaners were 26" models), however other shooters have told me they think the longer barrel makes the V3 a bit muzzle heavy. Field shooting mirrored my clay-target observations in that flushing pheasants and incoming geese seemed easier to hit, while my luck with flaring doves and pass-shooting ducks was spotty. (For whatever it’s worth, those birds are faster.) Frankly, I feel some muzzle heaviness is a good thing when it comes to shooting wing and clay, and given that the V3 comes with a light-contour barrel, my inclination would be to use the longest barrel I could get my hands on.

As noted, recoil reduction is now a key sales driver in premium semi-automatic shotguns, and top manufacturers have responded with some very clever mechanical solutions. The V3 relies instead on the VersaPort’s efficiency in shedding pressure, prompting Remington to proclaim it “the softest-recoiling auto in the field.” A vivid graph on the company’s website shows that peak recoil force from the V3 is markedly lower than from competing models, and because the kick is more gradual, it’s less jarring to the shooter.

Subjectively, I can vouch that the V3s I fired delivered recoil typical of a mid-weight 12 gauge and are on par with my 11-87, which is a full pound heavier. Frankly, I didn’t much notice the recoil when shooting the new gun, though certainly I could feel the difference switching from light to heavy loads. One who did notice was our least experienced test shooter, who was beaming after her round of clays. “I figured the V3 was going to rock me off my feet, and not in a good way. I can happily say my experience was to the contrary,” she wrote. “I believe I uttered the words, ‘Wow, that’s it?’ after shooting the V3 using 3" magnum loads for the first time.”

The contrast between her perception and mine, I believe, reflects the subjective nature of judging felt recoil. A lot depends on your experience and mindset. Though everyone knows it when recoil hurts, it’s hard to quantify when it doesn’t. Remington’s approach to reducing felt recoil by venting excess gas more efficiently is quite novel and doesn’t add extra parts to the gun.

A Determined Launch

There’s one more box that the V3 ticks off, and it’s an important one—the affordability box. As this is written, black-synthetic V3s are going for $800 or less from some sellers. That’s a different ballpark than any competing model, and by comparison, the affordability box isn’t going to be a selling point on the others’ checklists. The fact that Remingtons are the category’s only U.S.-made entries will also be important to many folks.

The inaugural Field Sport 12-ga. variant is intended as a do-everything gun, the kind of versatility that appeals to many shooters, including one-gun-for-all-game hunters, along with new shotgun owners, who may well benefit most from a design that shifts weight to the middle and dampens felt recoil. The moderate pricing is important to both groups.

There’s every reason to think the V3 platform will be adapted, and later on I bet we’ll see competition guns, youth guns, sub-gauges, dedicated waterfowl and turkey models, and more. One intriguing possibility is a semi-automatic with a folding stock, a feature tactical and home-defense shooters love on their pump shotguns, but which hasn’t been an option for mainspring-dependent autoloaders.

The gun’s relatively modest launch actually reflects a determined new management credo at Remington, the overriding principle of which is to make darn sure a product is 100 percent right before it goes out the door. The company knows it must rebuild its standing with the shooting public, and we’ll know soon if the V3 is a genuine step in that direction.