The patent for the first detachable box rifle magazine was filed in 1879 by James Paris Lee, and the resulting Remington-Lee Magazine bolt-action would go on to birth a whole family of box-fed descendants while influencing the designs of countless others. Military orthodoxy of the day kept the fixed internal magazine relevant for a bit longer—despite the successful fielding of detachable-magazine-fed models such as the Browning Automatic Rifle and the Thompson submachine gun—but prior to World War II it was clear that the removable box was to be the feeding mechanism of the future for rifles. Handgun inventors caught on even more quickly, and the conveniently portable ammunition containers consistently started being utilized in their designs as soon as the early 1890s. The benefits were just too great to ignore.

Yet, nearly 140 years after Lee’s innovation, shotguns that deviate from the same tubular-magazine-fed design in use since the advent of the repeating scattergun remain curiosities, despite those same benefits applying to box-fed shotguns as well. Sure, in the past dozen or so years a handful of exceptions to this rule have arisen—mostly as variants of the AK and AR patterns (or at least designed to superficially imitate them)—but they still remain a meager slice of the shotgun market and more often than not are produced abroad. That is, until now: The box-fed shotgun just went mainstream.

The world of the pump-action shotgun has long been dominated by two models, Remington’s 870 and Mossberg’s 500/590 family, and for 2018, both of these revered American platforms are being offered in their first ever detachable-box-fed renditions: the 870 DM and 590M, respectively. Pump shotguns have a lot going for them, but their reliance on the tubular magazine also hamstrings them with a number of ammunition-related shortcomings. A cumbersome loading procedure results in glacial reload times, a problem exacerbated by the typical shotgun’s low capacity, which necessitates more frequent topping-off of the firearm. And with bandoliers having fallen out of fashion a good while ago, convenient options for carrying the spare shells needed for a reload are limited; more or less, any ammunition that isn’t present in or on the gun won’t be available during a time of need. By introducing the detachable magazine to their mainstay pump-actions, Remington and Mossberg are seeking to address these limitations while still offering an unfailingly reliable product.

A comparison of box-fed and tube-fed shotguns reads a lot like the semi-automatic pistol versus revolver arguments that have been occurring in gun shops around the globe for at least the past generation. Although the revolver still has plenty of adherents, the semi-automatic has beaten the wheelgun—in no small part due to the ease of use and increased capacity of its detachable magazine. As you’ll see below, Remington chose to focus on the former in designing its first box-fed Model 870; Mossberg’s 590M, instead, prioritized the latter.

For all but the most practiced of shotgun users, removing an empty and inserting a fresh detachable box that allows the firearm to immediately return to full capacity is an exponentially quicker and easier operation than collecting shells from the side of the gun or your person and individually inserting them into a tube in order to top-off. This is particularly true if the user is already familiar with the process because of similar procedures required to reload his or her handguns and rifles—which, at this point, virtually everyone reading this magazine is.

Yes, if one possesses the time, manual dexterity and commitment to go the Malcolm Gladwell/10,000-hour route of gaining proficiency, it is possible, through tireless repetition, to develop the muscle memory necessary to run a tubular magazine like a professional competitor, but that’s not a realistic expectation of the typical shotgun-wielding home defender. Practically speaking, for many, a tube-fed shotgun that runs empty during the course of a defensive scenario is fairly likely to stay that way. Remington’s 870 DM and Mossberg’s 590M make a mid-fight tactical reload a much more feasible proposition for the Average Joe.

Another area where the box-fed shotgun shines is in its potential use of dedicated magazines carrying specific loads. With its ability to fire anything from birdshot and slugs to flechettes and bean bags, the shotgun is quite possibly the most intrinsically versatile firearm, and detachable magazines allow that flexibility to be even more fully realized. Whether you’re a hunter who quickly needs to shift from a turkey load to a slug, or a peace officer who must swiftly transition from buckshot to a breaching round, detachable box magazines allow your shotgun to rapidly adapt to a host of different missions. Just drop your current magazine, retract the slide to eject the chambered shell, load the appropriate box and run the action closed again. With practice, and properly marked magazines, it should take only seconds—not so with most tube-fed guns.

At the time of their respective launches, both companies came to market with multiple SKUs at the ready—Remington with six and Mossberg with two—and I’ve had the chance to extensively run what amounts to the base model of each of these two new lines. While it’s highly unlikely that the detachable box magazine will ever usurp the dominance of the under-barrel tubular magazine among shotgunners in the same way that semi-automatics have overtaken revolvers, range time with these two similar-but-different scatterguns leads me to believe there’s plenty of merit to the box-fed shotgun concept.

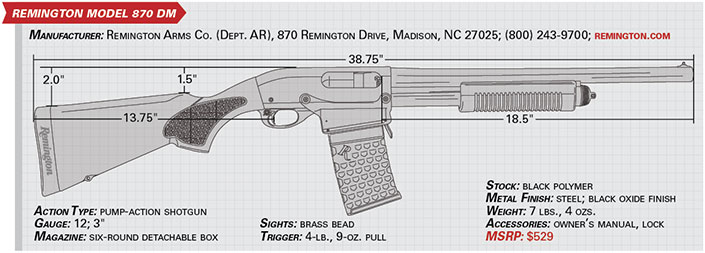

Remington Model 870 DM

Introduced in 1950, and manufactured to the tune of 11 million units since that time, the Remington 870 stands alone as the most-produced shotgun in history. Yet of the countless gauges, grades, barrel lengths, finishes, sights and stock materials in which Remington has offered the guns during the past 68 years, the six variants of the Model 870 DM are the first to feature a removable magazine.

Designed and manufactured in-house by Remington with an emphasis on reliability and versatility, the 870 DM feeds from a single-stack, six-round-capacity box magazine that can accommodate either 2¾" or 3" 12-ga. shells interchangeably. A camouflage-clad Predator configuration ships instead with a three-round box. Each shotgun comes with only one magazine, however, spares can be purchased aftermarket from the company for $35.

When filled with 2¾" ammunition, the 870 DM’s topped-off capacity of seven shells places it on equal footing with the company’s tube-fed home-defense shotguns—which generally have room in the tube for six 2¾" shells or five 3" shells. When loaded up with 3" magnums, however, the new model accommodates an extra round relative to its tubular stablemates—since shell length has no bearing on capacity in a box magazine. And, of course, a quick magazine change allows shells eight through 14 to be quickly brought to bear. Remington initially began research into the development of new pouches that would help facilitate the carrying of extra magazines, but quickly found that it wasn’t necessary—as nearly all M14-style magazine pouches and many AR-10-style pouches are already compatible with the 870 DM boxes.

The portion of the magazine that mates with the receiver within the magazine well is made of steel, while the section that protrudes downward from the well is a glass-filled nylon. Shallow texturing on the sides of the box do little to enhance purchase, but deeper grooves on the front and rear of the magazine are much easier to hold onto. Each box uses a bright orange, anti-tilt follower and can be easily disassembled by depressing a button in the bottom of the baseplate.

I found the 870 DM’s magazines to be quite effortless to load to capacity, thanks to a relatively pliable follower spring, as long as care was taken to avoid hanging up a given shell’s rim on the edge of the brass of the shell beneath it (easier with high-brass loads than low-brass ones). At first glance, the stamped steel feed lips appeared to be somewhat flimsy, however, repeated drops from shoulder height directly onto the lips did not result in any apparent damage to those parts. Empty, the six-round magazine weighed only 9 ozs., and filling it to capacity with 2¾" shells loaded with No. 4 buckshot brought the weight up to 1 lb., 2 ozs.

In order to pull off proper functioning of the 870 DM, the receiver of the standard Model 870 had to be machined differently to allow an aluminum magazine well to be bolted into place. The tube-fed gun’s trigger group and breechbolt also had to be modified, and a lug was designed to traverse the feed lips, strip a shell from the magazine and chamber it when the action is closed. While the magazine tube is still present in order to serve as a guide for the pump-action fore-end, the tube is now empty and the carrier has been altered to dispense with the elevator. Magazines are dropped from the shotgun via a paddle-style release located just forward of the magazine well.

Apart from the changes necessary to accommodate loading from a separable box, the 870 DM is in all other ways a Remington Model 870. The shotgun’s receiver is milled from a single block of steel, and the one-piece slide assembly makes use of dual steel action bars. A spring-loaded extractor is contained within the right side of the bolt, and an ejector is found on the left side of the receiver. As is typical of the 870, the DM’s action bar lock is located forward of the trigger guard on the left side of the gun, and the crossbolt safety is found just behind and above the trigger. Right-handed shooters will find this orientation to be convenient—for southpaws, the arrangement is sub-optimal.

The base-model 870 DM has an 18½" fixed cylinder-bore barrel topped by a single bead, a 3" chamber, a black synthetic stock with a SuperCell recoil pad and a corncob-style fore-end. Overall length of the shotgun measures 38¾", and, with an empty magazine, it has a weight of 7 lbs.,4 ozs. The receiver offers no accommodation for the installation of an optic. Also offered by Remington are: a very similar hardwood-furnished model; a tactical variant with ghost-ring sights, a pistol grip and a ported REM choke; a hunting model with a thumb-hole stock and two TruLock choke tubes; a Magpul version wearing that company’s SGA buttstock and MOE fore-end; and a TAC-14 “firearm” option featuring a Shockwave bird’s head grip and an abbreviated 14" barrel.

The presence of a traditional, rifle-like magazine well on the 870 DM makes no-look magazine changes possible, and the fact that they click audibly into place using simple upward pressure makes reloading the shotgun a quick and simple process—something that can rarely be said of smoothbores. Empty magazines did not reliably drop free of their own accord when the release lever was depressed. Side-to-side wobble of the seated magazine was minimal, however, it could be jostled forward and back a considerable amount; regardless, through 200 rounds of function testing, using numerous types of loads, I was unable to force any malfunctions of the Remington. As long as proper slide-racking technique was employed, the 870 DM ran 100 percent.

The presence of a traditional, rifle-like magazine well on the 870 DM makes no-look magazine changes possible, and the fact that they click audibly into place using simple upward pressure makes reloading the shotgun a quick and simple process—something that can rarely be said of smoothbores. Empty magazines did not reliably drop free of their own accord when the release lever was depressed. Side-to-side wobble of the seated magazine was minimal, however, it could be jostled forward and back a considerable amount; regardless, through 200 rounds of function testing, using numerous types of loads, I was unable to force any malfunctions of the Remington. As long as proper slide-racking technique was employed, the 870 DM ran 100 percent.

On the range, the Remington’s slide was easy to actuate, the controls were intuitive to use and the trigger was excellent. Patterning was done at 25 yds. using Hornady’s 2¾" Varmint Express No. 4 buckshot ammunition. Using an average of 10 shots, the cylinder-bore barrel deposited 22 of the load’s 24 pellets (92 percent) within the target’s 21" inner circle, with a mean pattern size of 18". Of the 240 pellets fired in total, only a single flier ventured outside of the target’s 30" outer ring. This is a pretty typical result for buckshot through an unconstricted barrel, and given the shotgun’s intended close-range applications, would serve a home defender well.

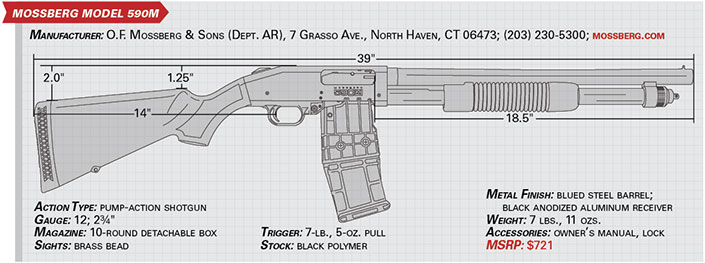

Mossberg Model 590M

Released in 1961, the Model 500 achieved immediate popularity due to its quality, affordability and modularity of design. In the mid-1980s, a few tweaks were made to the 500 in order to appeal more to the law enforcement and military markets (where Mossberg would go on to enjoy great success), and the resulting shotgun was dubbed the Model 590. While the Model 590M cannot lay claim to being the company’s first detachable-box-fed shotgun, or even its first box-fed 12 gauge—those distinctions belong to the 20-ga. Model 85B and the Model 195 bolt-actions, respectively—it does mark the first time that the concept has been applied to the august 500/590 family tree.

The most immediately eye-popping feature of the new 590M is its immense, double-stack, center-feed, 10-round magazine, supplied to Mossberg by Adaptive Tactical. Compatible only with 2¾" shells, the stock factory magazine affords the gun a prodigious amount of firepower. Only by extending the tube well beyond the barrel of the gun (or drawing from multiple tubes) can most home-defense shotguns achieve such a capacity.

Potentially upping the ante even further, the manufacturer also offers Brobdingnagian 15-round ($128) and 20-round ($140) spare magazines—in addition to a five-round ($101) option and additional 10-rounders ($112). At its widest point, the 590M magazine measures just shy of 2.5" across, making it dimensionally compatible with most .308 Win. double pouches already on the market. Empty, the factory 10-rounder weighs 1 lb., 4 ozs.; loaded up with 2¾" 00 buckshot, it adds 2 lbs., 3 ozs., to the weight of the gun.

Principally composed of thick, sturdy polymer, the magazines’ upper portion (where the double-stack assembly of shells transitions into a single column) and floorplate are identical—only the center section of the box, which is secured in place by eight screws, varies according to capacity. Thick ribs all along their circumference aid in the manipulation of the magazines, and hardened-steel feed lips and an anti-tilt follower help provide reliable feeding. The magazines are also easily disassembled for cleaning, however, filling the box to capacity does require some effort due to the stiffness of its ASTM A228 steel follower spring. As with the Remington, to ease the loading process, place the rim of the shell on the brass of the one beneath it (not the plastic hull) before attempting to push it down and slide it under the feed lips.

Six lugs molded into the upper portion of the magazine engage corresponding recesses milled into the receiver, resulting in surprisingly solid lock-up given the design’s lack of a conventional magazine well. Boxes must be rocked and locked into place, in a manner reminiscent of AK- and M14-pattern rifles, resulting in a somewhat slower reloading procedure that may require taking your eyes off of the target momentarily. In addition to machining the receiver differently, the 590M’s bolt, barrel and bolt slide (carrier) all had to be re-designed in order to ensure dependable function with a removable magazine.

Like all 590s, the bolt on the 590M locks up with a steel extension in the shotgun’s barrel when in battery, allowing the unstressed receiver to be composed of lighter-weight aluminum. With an empty 10-round magazine seated in place, the weight of the shotgun comes in at 7 lbs., 11 ozs. An extractor on either side of the bolt serves to pull shells from the chamber, and a user-serviceable ejector subsequently expels them from the firearm. An empty tubular magazine, again serving only to support the fore-end, is topped with a 590A1-type magazine cap. The 590M is partially compatible with Mossberg’s FLEX system of interchangeable components; the shotgun can accept any FLEX buttstock or recoil pad modules, however, the fore-end cannot be swapped out for FLEX components. And while 590M barrels are interchangeable with other 590M tubes, standard Model 500/590 barrels are not compatible with the new gun.

Placement of the 590M’s controls make the gun equally accommodating for both left- and right-handed users. A bilateral, helical, steel magazine-release button is located just forward of the trigger guard and can be actuated by pressing inward from either side. Other operating controls are found in the traditional locations for the 590: The action-lock lever is located on the left side of the receiver behind the trigger guard, and a two-position safety is centered on the shotgun’s tang.

Two styles are available at launch: a base model and an enhanced “Heat Shield” version, both of which are 39" long with an 18½" barrel and utilize a corncob-style fore-end. The former makes use of a simple brass bead front sight, while the latter utilizes ghost-ring sights and features a barrel shroud. Both options come as a cylinder-bore from the factory, however, the Heat Shield model accepts Accu-Choke-type choke tubes, while the base configuration is not threaded for use with chokes. Each variant comes drilled and tapped for the optional use of an optic.

Designing a reliable double-stack box magazine for use in a shotgun is an incredibly difficult feat to achieve—due to shell lengths varying widely (not only manufacturer to manufacturer, but even lot to lot) and a tendency of the rimmed ammunition housed within a box to lock rims with each other. Yet Adaptive Tactical pulled it off admirably. Reliability of the 590M was flawless, as you should be able to expect from a pump-action shotgun, and pressing the release button caused the magazines to fall from the gun without assistance from the shooter.

Initially concerned that the shotgun’s sizeable magazine would render it ungainly at the shoulder, I found throughout several hundred rounds of function testing such anxieties to be unfounded. Of course, moving the weight of the ammunition from a tube underhanging the barrel to a box centered between the shooter’s hands naturally does shift the gun’s center of balance rearward, but it’s hard to view this as a negative change within the context of a defensive shotgun. Even using a fully loaded 20-round box, four-second Dozier drills were commonplace. While circumstances requiring more than 11 shells of 12 gauge (let alone 16 or 21) to resolve will be few and far between for most of us, reloading from the safe confines of an indoor range was not at all difficult, although I can see how stress could serve to complicate the rocking and locking action needed for a reload. But it’s nothing that a little practice can’t rectify.

Initially concerned that the shotgun’s sizeable magazine would render it ungainly at the shoulder, I found throughout several hundred rounds of function testing such anxieties to be unfounded. Of course, moving the weight of the ammunition from a tube underhanging the barrel to a box centered between the shooter’s hands naturally does shift the gun’s center of balance rearward, but it’s hard to view this as a negative change within the context of a defensive shotgun. Even using a fully loaded 20-round box, four-second Dozier drills were commonplace. While circumstances requiring more than 11 shells of 12 gauge (let alone 16 or 21) to resolve will be few and far between for most of us, reloading from the safe confines of an indoor range was not at all difficult, although I can see how stress could serve to complicate the rocking and locking action needed for a reload. But it’s nothing that a little practice can’t rectify.

During pattern testing, the Mossberg 590M grouped incredibly tightly for a cylinder-bore shotgun. Using Federal Personal Defense 2¾", nine-pellet 00 buck, the average pattern size for 10 shots measured a remarkable 7.3" at 25 yds. So much for the notion of not needing to aim your shotgun. Yet surprisingly, a Galazan bore-measuring tool revealed that my test gun actually had a bore diameter of 0.734"—looser than the 0.729" standard for an unconstricted 12 gauge. Regardless, equipped with a red-dot sight, this shotgun is capable of making uncommonly precise shots.

While some will no doubt be hesitant to part with the proven utility of their tube-fed scatterguns, and can hardly be faulted for sticking with the tried and true, broader availability of the box-fed shotgun is a good thing, and it’s long overdue. Armed citizens and professional users alike will benefit from ditching the tube. Given the mission-configurable adaptability of the platform, I can see law enforcement agencies, in particular, taking a long, hard look at the potential adoption of a box-fed shotgun design for departmental use. Although they come at the concept from different directions, both Remington’s 870 DM and Mossberg’s 590M provide legitimate advantages not offered by the tubes of their siblings, and are, therefore, welcome additions to the shotgun market.