If a mega-bank or car manufacturer is struggling, the government (the current one, anyhow) might well declare it “too big to fail” and jump in with a cash bailout. But do you think that would happen in the case of an iconic gunmaker going through a rough patch? Ha!

And that’s just as well, because gun enthusiasts tend not to appreciate such interventions and, in the case of Remington Arms, it’s heartening to see a cultural elder working so intently to connect 200 years of gunmaking genius with bright young minds and forward-thinking technology.

On the heels of a downturn marked by rampant expansion, aborted model introductions and quality-control questions, the company is back to doing what it has done best for two centuries—it’s building guns. Naturally these include the legacy models many know and love, headlined by Model 870 shotguns, Model 700 bolt rifles and Marlin Model 336 lever-actions. But Remington Outdoor Corp. (ROC) is also innovating new designs with new manufacturing methods and new tooling. The company is determined to rekindle the shooting public’s allegiance to all-time favorites and fresh ideas alike.

In December I took part in a north-south junket to the twin hubs of Remington Country, a two-day shooting-press tour of manufacturing plants in Ilion, N.Y., and Huntsville, Ala. I went knowing Remington would put its best foot forward, but in a sense this was about re-opening doors after some difficult changes to the corporate structure and culture. As a Remington fan, I welcomed the resilience and show of corporate determination, and went hoping to come away impressed.

In December I took part in a north-south junket to the twin hubs of Remington Country, a two-day shooting-press tour of manufacturing plants in Ilion, N.Y., and Huntsville, Ala. I went knowing Remington would put its best foot forward, but in a sense this was about re-opening doors after some difficult changes to the corporate structure and culture. As a Remington fan, I welcomed the resilience and show of corporate determination, and went hoping to come away impressed.

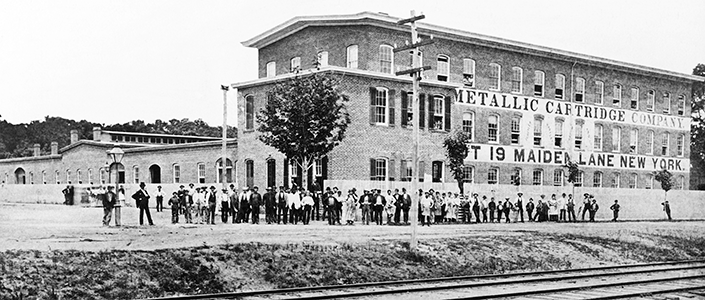

At Ilion we found a smokestack fortress that is so huge, so historic and perhaps so dated, that it was counterintuitive to envision the vitality we would encounter within. Today, 1,300 employees work at this survivor of America’s Industrial Revolution . Inside we saw plenty of honest wear-and-tear, but notably, we also encountered lots of cutting-edge, high-tech computer-numeric machinery. To be sure, some older tooling is still at work, and it appeared the managers and workers have deduced the best and most practical ways possible to merge old and new manufacturing practices and equipment. We saw precision-machined parts being subjected to stringent quality control methods, along with top-flight materials that aren’t always found in current trendy models. We saw sure-handed assemblers fretting over fit and finish. We’ll know soon what shooters have to say about current-edition Ilion-made 870s, 700s and Marlins, too. These models continue to move in the marketplace and, while I don’t have sales numbers to share, I saw several trucks being loaded with guns right off the assembly lines.

Mostly what I sensed was a hard-working culture of skilled labor, the kind that built our country and ensured that precious firearm freedoms could and would be within reach of Americans from all walks of life. We can’t afford to lose that.

The next stop, Huntsville, was predictably quite different, a park-like setting whose sleek, modern buildings presented a sharp contrast to the smoky brick outpost up north. The newly outfitted factory and its state-of-the-art tech center were still getting up to speed, but nonetheless the workforce there was building guns whose designs are newer and whose applications are in step with a new generation of shooters.

Remington’s 2014 acquisition of a large industrial campus in this southern aerospace center made headlines in both the firearm press and national news outlets. In unison, gun owners applauded the idea of America’s oldest gunmaker operating in such a gun-friendly state. It was apparent that settling in would take a while, and yet in several critical ways we observed things progressing at a rapid pace.

Remington’s 2014 acquisition of a large industrial campus in this southern aerospace center made headlines in both the firearm press and national news outlets. In unison, gun owners applauded the idea of America’s oldest gunmaker operating in such a gun-friendly state. It was apparent that settling in would take a while, and yet in several critical ways we observed things progressing at a rapid pace.

Repeatedly we heard how the company is tackling its quality-control issues and learned about an innovative new approach to merging R&D, marketing and operations teams in hopes of developing, perfecting and supplying new products that are truly ready for market. Everyone we met cited the commitment of all 350 employees to quality control. New Remington CEO Jim Marcotuli put it in perspective, with the frank admission that, “We know we need to fix it first, then tell the story. We need real results to speak for themselves, and while we can’t claim success yet, we’re committed to getting there. I don’t want to say we have fixed it yet. But we do want to offer transparency, and to say this is the path we’re on to getting it right.”

That path includes new guns stamped “Remington Huntsville, AL.” Our media group observed Remington’s first major new product in quite some time—the RM380 micro carry pistol—coming off assembly stations (and later got to shoot RM380s on an R&D test range). We also observed DPMS AR-style rifles and AAC silencers in production, and saw racks of newly machined R1 1911 slides. All the manufacturing equipment appeared to be spanking new, to go along with the renewed priority of customer satisfaction.

Production processes are being organized in “value streams” that conveniently co-locate machining, assembly, testing and packing operations to maximize efficiency and quality. Managers we met included both transfers from other Remington facilities and locals, many with engineering backgrounds in Huntsville’s booming automotive and aerospace economy. To help find employees that are a good fit, the state-run Alabama Industrial Development Training offers a 40-hour pre-employment course where prospective hires are given basic instruction in operating factory tooling. That, along with the fact that Huntsville has America’s highest per-capita engineer population, ensures that a top-notch work force is being assembled.

In addition, Remington operates a third gun-making unit, namely Dakota Arms, in Sturgis, S.D., devoted to building custom and semi-custom firearms. Along with Dakota and Nesika brand rifles, the company recently shifted its long-running Custom Shop from Ilion to Sturgis, and so bread-and-butter Remingtons are re-stocked in exhibition-grade wood, hand finished and embellished, accurized to the nth degree and/or modified for special purposes, all according to customer specs, tastes and budget.

This is fine-art gunmaking, where the volumes are low and the quality and prices are just the opposite. It’s worth noting that no other major U.S. manufacturer presently possesses the in-house competence to compete with legacy European firms in this rarefied arena.

A close look behind the doors at the Ilion, Huntsville and Sturgis plants makes it evident that Remington is rebooting its hopes and its standing with shooters by doing what it must do—building good guns for a shooting public that’s looking for quality and fair deals. To echo Marcotuli, I’m certainly not in the position to say the company’s troubles are fixed, but I can report that an ambitious and promising plan is moving forward to reclaim Remington’s rich legacy as it prepares to celebrate the biggest milestone ever in American gun manufacturing.