With proven production lines, motivated workers and new owners, Remington’s comeback in ammunition production brings a high-value supply stream aimed at offsetting America’s lingering shortage.

Redemption is a part of the human condition all of us rely on for course correction. It’s a big part of our faith, Western culture and the American way. God willing, second chances come for those who bring troubles on themselves, as well as for victims of circumstances beyond their control.

Last fall, however, for employees at the Remington Ammunition factory in Lonoke, Ark.—and by extension for the entire community—it appeared there would be no redemption. After years of financial struggles, and as the nation recoiled from the COVID pandemic, Remington Arms filed for bankruptcy on July 27, 2020—its second such filing in two years. National headlines screamed out the irony of declaring bankruptcy even as demand for firearms and ammunition surged off the charts.

Last fall, however, for employees at the Remington Ammunition factory in Lonoke, Ark.—and by extension for the entire community—it appeared there would be no redemption. After years of financial struggles, and as the nation recoiled from the COVID pandemic, Remington Arms filed for bankruptcy on July 27, 2020—its second such filing in two years. National headlines screamed out the irony of declaring bankruptcy even as demand for firearms and ammunition surged off the charts.

Though Remington’s ammunition business was healthier than its other units, when the axe started falling on company operations in four states, Lonoke wasn’t spared. Furloughs and layoffs thinned the workforce at what had long been the area’s biggest employer, and those who kept their jobs didn’t know what they’d face from one day to the next. Vital raw materials and components were in short supply, and machinery was sidelined for want of commonly needed parts. Regardless of the remaining workers’ determination and clever hacks devised to keep the machines running, production dropped and more were sent home.

Meanwhile, news circulated about a September 30, court-administered liquidation sale of Remington assets. Unlike the reprieve that forestalled the 2018 bankruptcy, not even the hottest sales market ever could save the company this time. Soon employees received a letter stating that their jobs and the factory’s future were uncertain. Tensions rose in the town of 4,250 residents, and Mayor Trae Reed recalls, “People at the plant were nervous. In a previous job, I saw companies and plants dismantled, and those were some of the worst days of my life. There was a concern it would not get back up and running.”

When the auction results were announced, word that Vista Outdoor was the plant’s new owner ricocheted through the huge, largely idled factory. Frantic online searches for “Vista” led to relief and jubilation. While the gun-blog crowd fussed about the logic and motives of the corporate owner of Federal, CCI and Speer (plus other outdoor firms) snapping up a competitor, Lonoke workers weren’t troubled in the least. One of them would later say, “I hadn’t heard of Vista before, but when we learned it was an ammunition company, that was a ray of hope. When we learned they own Federal, we said, ‘That’s it—we’re one big family now.’”

Though acquiring an ammunition company is far more complex than purchasing a house or a car, because of the circumstances, Vista executives hadn’t done a walk-through or kicked the tires before submitting their winning bid. But it was hardly an impulse buy.

“[Vista CEO] Chris Metz and I talked often about acquisition targets, including Remington,” acknowledged Jason Vanderbrink, president of Vista’s ammunition brands and the new boss at Remington. “Even before what happened in the past year, we were thinking strategically: 205-year-old brand, American-made. In fact, we viewed Remington as a must-have. Opportunities like this don’t come around very often.”

Post auction and prior to the settlement, an advance team led by soon-to-be plant manager Adam White visited the campus. An up-and-comer who earned his spurs working for CCI in Idaho, White shared, “My first afternoon, about 3:15, I walked through to get a drink, and the lights were off. It was just the cleaning crew and me. It amazed me when I realized that, for the first time in 11 years in an ammunition plant, a department wasn’t running at full capacity, didn’t have enough material to keep going. But we knew a lot of furloughed teammates were out there, anxious to get back to work. I had no doubts we could do that.”

The sale closed shortly thereafter, and work began in earnest. “The day after closing, I was here,” Vanderbrink said. “First, we had to let employees know that ammo is all we do. We had to let them know we are not an investment banker but instead would invest in this facility and load it up with skilled labor and raw materials. Our message was: ‘We’ll work together, and you needn’t worry about us selling this business in a few years. Ammo is what we do.’

“The factory itself was in good shape, capable of doing what we needed. We just had to get the people back, and that’s not easy. It doesn’t make sense to bring people in faster than you can get them into your system and train them.

“After an acquisition, you wonder what the workforce is like. Well, the workers in Arkansas are second to none. I love their pride and soon knew the labor piece would not be an issue,” Vanderbrink recalled. A meeting with all furloughed workers was held during Vista’s first week, and the rebound picked up steam. “Every day since, we have produced more ammunition than the day before. It’s increased steadily and matched expectations Chris Metz and I had coming in. The factory is actually running a little better than we expected.”

Though the prospects couldn’t have been better for the speedy return of America’s second- or third-largest source of ammunition, that news appeared to be moot to disgruntled shooters confronting empty retail shelves, online backorders and an ammunition supply chain tapped bone-dry. Despite working 24/7, manufacturers got hammered by frustrated customers; their phones rang non-stop and message-board commandos called for their heads.

In early December, I asked Metz for Vista’s perspective regarding how the acquisition might affect the shortage, and he was cautiously optimistic. “Our acquisition of Remington [ammunition] is ahead of plan,” he said. “We’ve been working to re-hire 400 to 600 furloughed workers, have been re-training them and getting the manufacturing processes back in place. Remington ammunition should be coming back on the market in early January. We all grew up with the brand, we love it and we know we’re not alone.”

Following our chat, I dug deeper, phoning customer service at the Remington factory. My article on the status of America’s year-long ammunition squeeze was due, but I felt we owed American Rifleman readers more than just another refrain about shelves being bare. More than anything, I wanted to provide credible insight into when it would end.

Lucky to get through after a couple of tries, I spoke with a sweet lady who couldn’t answer the loaded question, but confidently confirmed, “Production is coming back. We’re running more every day. More people are coming back to work every day. Oh, everyone is going to see Remington come back.”

A Demise Exaggerated

A few months later, American Rifleman was invited to come to Arkansas to witness the progress. It was too late to inform reports already published on the ammunition crisis, but that story wasn’t going away. America’s shooters remained (pardon the pun) up in arms, though there had been a not-so-subtle shift from “can’t find any” to “can’t afford it” (expletives deleted).

NRA Publications Editorial Director Mark Keefe, Sales Manager Tony Morrison and I drove west through vicious spring storms, then on a symbolically bright Monday morning, we queued up to get through the plant’s front-gate security office. There we joined about 20 new hires completing paperwork and getting their employee badges, a routine occurring more often than not since Vista’s takeover.

Inside the main building, we met the Vista crew, razzed them about changing teams, then proceeded right into a production room where lead wire coiled inside 55-gallon drums was fed into extruders that transformed it into bullet cores. For much of the next two days, I tagged along with Keefe and “American Rifleman Television” videographer Jake Stocke as they filmed segments on the myriad operations required to produce Remington’s extensive ammunition menu. The workers were engaged, busy and friendly, and their jobs varied from one spot to the next. Several, epitomizing the hybrid IT specialist-machinist role of modern manufacturing, rotated through banks of computerized cutting and forming centers. Others, like the fellow squeegeeing rimfire priming trays and the ladies hand-inspecting finished rounds, were studiously hands-on. It was a hive of skill and activity, and it’s hard to imagine a busier scene, though we learned that more hiring was planned. Typically, around 800 folks are employed there, though that number fluctuates, and the new managers weren’t yet sure how high it would go now.

The spectacle of fresh 9 mm Luger cartridges raining from loaders into bins reminded me of our pent-up demand. A conveyor-belt river of Core-Lokt .30-’06 Sprg. rounds conjured thoughts of treestands and bucks, and an endless train of boxes full of STS shotshells translated into shattering claybirds. I thought then and will repeat here: America, ammunition you need is on the way.

In a quiet lobby, I met three employees—Charles Carter, Shontelle Ford and Sandra Strickman—who collectively possess close to a century of tenure with Remington. Foremost, they talked about family. There’s a general sense of it among the workforce, but, more literally, many employees have relatives as co-workers. That made the past year even tougher.

A shotshell supervisor, Carter said, “The saddest part was receiving those letters, that if the company wasn’t sold by so-and-so date, we’d all be terminated. I think a lot of us did a lot of praying.” Ford, who returned from furlough to her job in centerfire production, recalled colleagues being “scared” and that “quite a few people were lost.”

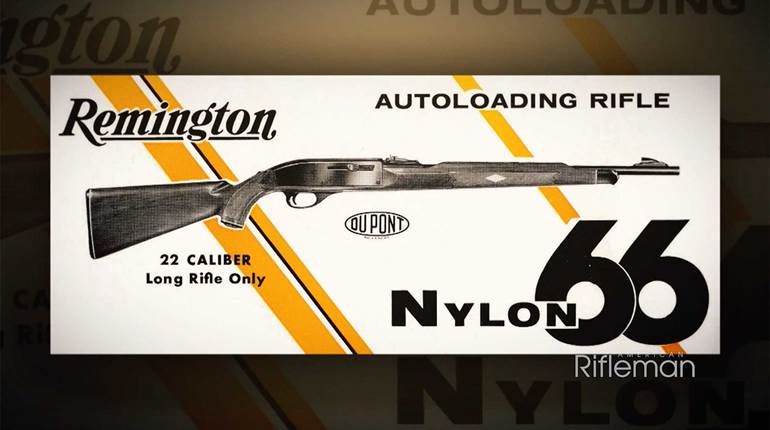

Strickman has held several jobs at Remington since starting in 1973 and is determined to pass the 50-year milestone before retiring. “I never got laid off,” she said, “and it was a very stable job back in the days when the owner was DuPont (1933-93). But things changed drastically, and we could see the recent owners didn’t care as much. But now, with Vista coming in, it was a blessing. We feel confident our jobs are in a good place.” It didn’t take long for me to recognize Sandra’s voice. She was the customer service rep from my December phone call who assured me Remington ammunition was coming back.

Enduring Headstamps

At the time the Lonoke plant opened in 1969, Remington was dominant in the firearm industry, and the new facility fell in step, pushing out green-and-yellow boxes of rifle, pistol, shotshell and rimfire cartridges. Capacity there was enormous, and it sat on 1,200 acres. Presently there are 1 million square feet of manufacturing space, and the grounds include a trap/skeet range that hosts youth clubs and local shooters. A sporting-clays course is now in the works. As before, Remington ammunition was favored for all commercial applications and issued to law-enforcement and military units, including U.S. forces in Vietnam.

Feeding the nation’s insatiable rimfire appetite—more than a billion rounds yearly—is skill- and labor-intensive and requires hands-on creation of the priming compound that goes into each tiny case (above).

For nearly a century, Remington and subsidiaries Union Metallic Cartridge and Peters had been leaders in ammunition innovation. Their proprietary rounds helped to set the bar on firearm performance, all-timers like .22 Long Rifle (1887), .35 Rem. (1908), .44 Mag. (1955), 7 mm Rem. Mag. (1962) and .223 Rem. (1964). Influential firsts also included the Core-Lokt tapered-jacket, controlled-expansion bullet (1939) and plastic-hulled shotshells (1960). The synergy between Remington’s firearm and ammunition houses benefitted shooters worldwide.

The move to Arkansas did nothing to impede that creativity. In year one, the .25-’06 Rem., and .25 Rem. Rimfire Mag. cartridges emerged, followed by notable developments such as 7 mm-08 Rem., .416 Rem. Mag., the Ultramag family and .300 Blackout, plus Duplex and Nitro 27 shotshell loads. More recently, Big Green developed well-regarded Golden Saber handgun loads and a quiet-shooting Subsonic line, but the financial battering eventually took its toll.

“Our engineering lead left as part of the bankruptcy, and we were very short on talent,” said longtime employee Nick Sachse, who has continued as director of product management. “Remaining development team members got pulled into production work. We were still developing new products on a very limited budget, but those projects were suspended in the bankruptcy.”

That’s changing, as Vanderbrink vowed, “we’ll be pouring in resources to innovate at Remington,” thereby echoing Metz, who told news sources, “You’ll see more innovation from Remington in the next 10 to 12 months than you’ve seen in a long time.”

One major resource is Jared Kutney, promoted from senior product developer at Federal to take over as Remington’s senior director, design engineering. “We have opportunities to make improvements and line extensions, related to components and production-cost efficiency. There are things all Vista ammunition units do well, and we can learn from them. But it also goes the other way. We came in and saw how Remington does certain things, good solutions we then passed on to corporate partners. The sharing will strengthen all of us.”

As Kutney views it, “Remington is the brand that’s affordable and always does the job well. It’s not necessarily a leader in niche categories—a current example is extreme long-range—and we’re not trying to be something we’re not. One opportunity area is development of an in-house premium projectile, and you will see exciting things with Core-Lokt. Down the road, bullets from other Vista brands may be added. There’s tremendous opportunity and tremendous interest from both internal and external applicants as we get staffed-up in engineering.”

In fact, help is coming from multiple directions. “I’ve learned that Vista companies regularly get ideas or feedback through their marketing side, that is, from customers and dealers,” Sachse added. “Remington’s marketing team before was quite small and had to split its time between so many categories and brands that our ideas had to come from within. Now we have this new channel, part of a collaboration where all the partners share ideas and together figure out where they best fit in.”

Keeping It Big, Keeping It Green

No one wants to see Remington become Federal or anything other than the successful ammunition supplier it’s been for generations. Everyone involved—most emphatically Jason Vanderbrink—talks about fraternal connections between companies, but he insisted, “Remington will be Remington—shooters need to know that firsthand. It won’t be CCI, won’t be Speer, won’t be Federal. But when any of our brands come up with technology worth sharing, sure, we’ll learn together.”

Incoming management was relieved to find the plant’s machinery and production lines (below) in “good shape to do what we need.”

Vanderbrink continued, “Remington’s strengths are well-known. About half of all rifle hunters shoot Core-Lokts. On the clay-target side, Premier STS and Nitro 27 are as good as it gets. But a weakness is law-enforcement product, where Speer Gold Dot is the king. So, naturally, we will leverage what we do best.

“New-product development is Vista’s strength. Federal, CCI and Speer all have a very innovative culture and mindset, but it was quite the opposite when we came in here. Remington’s not alone, however, because many companies in recent years pulled back on R&D. That’s too short-sighted for me. We need to meet demand, but also to be looking three to five years ahead. When the market was down, Vista ammo companies reinvested and are now reaping benefits in legacy business. Same will hold true for Remington.”

More tricky, perhaps, will be polishing up a Remington brand that suffered major hits because of the firearms’ diminished quality and resulting fiscal woes. Though the ammunition had little or nothing to do with either, guilt by association happens.

Jason Nash, Vista VP of Marketing, and Joel Hodgdon, as in-house marketing director, are charged with ensuring Remington Ammunition wields the same clout as in years past, and both were full of optimism.

“We may be starting at a low point, but it’s as challenging and fun to work on a brand with room to grow as it is working for brands on top,” Nash said. “Here’s a factory that was under-utilized, and we are bringing it up to full capacity. That’s already making a positive impact. The brand has been lacking new-product energy, but it’s coming.

“We’re doing some testing and working with new creative partners on a look that’s true to company roots and really different than anything from Vista’s other brands. Plus, we’ve brought in Ted Nugent as the brand spokesman, and no one is as brash as Ted. That’s Remington Ammunition making a statement, and it’s being heard because Remington actually has the biggest database of all of our brands.

“In the past, Remington heavily promoted its firearms, which was its legacy. But we’re an ammunition company, and so it’s important to put ammo forward and first,” Nash explained. “We don’t need to make Remington trendy. There’s nostalgia for the brand—it’s original Americana. Why not embrace that history? The boxes may change a little, but they’ll still be green.

“We’re casting a wide net for raising visibility. So how do you reach 8 million, 10 million new gun owners [from 2020]?” Nash asked. “We know a lot of people are coming to our websites, so we put a lot of emphasis on the content there. Though our industry doesn’t advertise on social media, we’ve placed advertising in magazines where we’ve never been before, like Good Housekeeping, and it has worked well. Partners like the NRA also have great resources for new shooters, and we’re glad to share those articles.

“We’re still setting goals,” Nash said, “but when we look at how Remington scores when actual end users are asked if they would recommend the brand or product, it’s positive.”

Just before our American Rifleman road trip, a video was posted featuring Jason Vanderbrink doing a factory walk-through. It was upbeat, but not all sweet talk. “You know what? I am sick and tired of not being able to find Remington ammunition on the shelves,” he said. “We are fixing that. American manufacturing is about to roar, and Remington Ammunition is back.”

That was six months ago. Has the situation changed where you are? My one-man survey of five retail gun stores and a bunch of online sites says it’s well on the way. More importantly, it says that Remington ammunition is here to stay, which hopefully bodes well for other Remington products.

Standing Tall: The Shot Tower Legacy Lives On At Lonoke

Standing Tall: The Shot Tower Legacy Lives On At Lonoke

Visible from nearby I-40 is an 11-story, beet-red obelisk rising like an exclamation point from the Remington ammunition works’ north end. It is both a relic of the smokestack age and a working structure instrumental in the production of the lead pellets the company loads into its shotshells. In a workroom at the top, molten lead is screened and dropped down an open shaft to collect in a water bath at the bottom. The individual lead droplets cool and harden on the way down, but, more importantly, the free-fall transforms them into spheres.

The dropped-shot method was invented in England in the 1780s when plumber William Watts experimented by repeatedly adding stories to his house and digging a pit beneath it until he obtained the uniformly round pellets he’d envisioned. The method soon spread, and through the 1800s, dozens of shot towers were erected across the U.S. A few of them live on as tourist attractions, including examples in Wythe County, Va., (reputed to be America’s oldest), Baltimore, Md., and Dubuque, Iowa. The rise of alternate shot-production methods in the 20th century made the towers all but obsolete. Remington’s square-sided monolith is just one of three active shot towers remaining in North America, along with those at the Winchester plant in Illinois and at Aguila in Mexico. This matters in shotgunning circles, particularly to some champion clays shooters who insist that dropped shot is more perfectly spherical than other types and thereby yields denser, more uniform patterns. So demand lives on for an old-tech product available in limited supply.

So far as we know, the Arkansas tower from 1969 was the last one built in North America. Interestingly, the Mexican tower was also Remington’s doing, as part of a production facility it developed for a short-lived outsourcing effort in the 1950s. After less than a decade, it was sold to the company that formed Aguila.

The day we ventured up the Lonoke tower coincided with the return of technician Mike McNeill. After working at the Remington plant for 45 years and producing tons of grade-A shot pellets in the process, McNeill retired in 2017. But, upon hearing so many good things about the new ownership, he told us he wanted back in. We found him at the smelter, liquefying 125-lb. ingots in preparation for transforming them into a lead product worth its weight in gold to avid shotgunners.