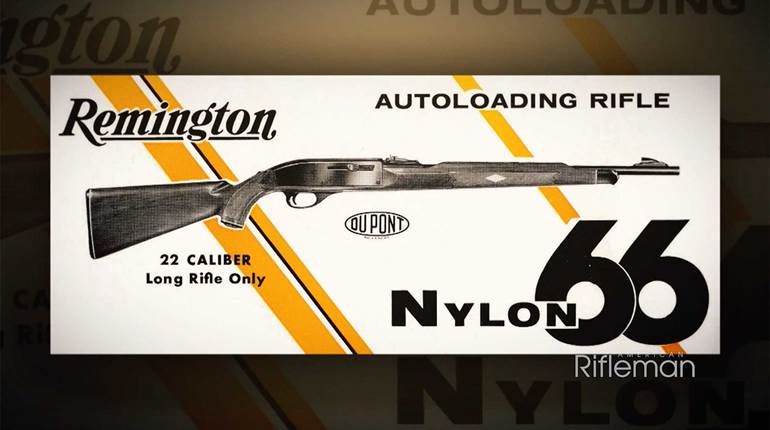

This article, “Fast And Fancy,” appeared originally in the October 1974 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the monthly magazine, visit NRA’s membership page.

Far from resembling long, lean movie gunslingers like John Wayne, Gary Cooper and his contemporary, William S. Hart, he stood only a stumpy, barrel shaped 5’, 5”. Caught up in a crowd, he looked commonplace. But with one or a pair of handguns, he could erupt fire like a small gun turret.

This was Ed McGivern, reputedly "the fastest gun in the world." Born [over] 100 years ago at Omaha, Neb., Oct. 20, 1874, of immigrant Irish parents, he became by vocation an outdoor sign painter. But by instinct, self-training, research and infinite diligence, he made himself the foremost handgun shooter during the period between the two World Wars.

Ed McGivern demonstrates fanning (above) with a Colt Single-Action Army.

Ed McGivern demonstrates fanning (above) with a Colt Single-Action Army.

Nebraska being too far east for him, he spent most of his adult life at Butte, Lewistown and Great Falls, Mont., and billed himself in public appearances at fairs and other events as "Ed McGivern of Montana." Except for his high-peaked cowboy hat and remarkably sharp blue eyes, however, his appearance yielded no clues to his fantastic skill and speed with handguns.

World Record Holder

McGivern's crowning feat as recorded in The Guinness Book of World Records took place when he was 58 years old (he lived to 83) while on an exhibition tour. Of it, the standard sports reference book says:

"The greatest rapid-fire feat. Ed McGivern fired two times from 15 ft. five shots which could be covered by a silver half dollar piece in 45/100's of a second at the Lead Club Range, South Dakota, Aug. 20, 1932."

The phenomenal performance was no fluke. On Sept. 13, 1932, at the 163rd Infantry Armory at Lewistown, McGivern fired a five shot group into the outline of a hand in 2/5ths second, according to the timer. That Dec. 8, he fired 20 five-round strings, four of them in 2/5ths second.

Although hailed as an inspiration to latter-day fast draw shooters, McGivern apparently thought of himself more as a pioneer and guide to law enforcement officers whose dangerous duties required sure, fast shooting. Of his array of 140 experimental, training, exhibition and aerial shooting feats, at least 15 were designed specifically for police work.

From the start of his shooting career, he worked methodically up to his unsurpassed eminence. As a youngster, he sold eggs to buy his first shotgun. Good at mathematics and the sciences, he worked his way through Creighton University, Omaha, for nearly four years. A trip with relatives to Wyoming, then swarming with pistol wearers, prompted his resolve to become "a scientific combat shooter"—not a showoff gunslinger.

Fascinated by firearms, he nevertheless made a lifelong business of outdoor sign painting. But he soon opened a shooting gallery in Butte. A friend gave him his first large-caliber revolver, a .41 Colt. With it he began to shoot aerial targets single-action and managed to hit a few doubles. Soon he discarded pre-conceived practices and current ideas on handgunning, and launched into a world of personal research. It was said of him in this period that he studied neurology, anatomy, psychology and physiology and became proficient at ballistics, mechanics and practical electricity.

Smith & Wesson .38's include top-break Model 1891, cal. .38 S&W (center) and pair of .38 S&W Special Military and Police Target models (discontinued 1941). Top revolver has special trigger guard for double-action firing.

Smith & Wesson .38's include top-break Model 1891, cal. .38 S&W (center) and pair of .38 S&W Special Military and Police Target models (discontinued 1941). Top revolver has special trigger guard for double-action firing.

Developing his own electric timing devices, he coordinated for one of them three stopwatches fined down to record 1 /20ths of seconds and verified by the U.S. Bureau of Standards. Although he at first used semi-automatic pistols such as the Savage .32s, he soon found that he could achieve a faster rate of fire with a double-action revolver. Ultra-skilled muscles and reflexes proved speedier than recoil-operated mechanisms.

Fortunately for McGivern's shooting career, his transition from single-actions and semi-automatics to the double-action revolvers coincided with the development and improvement of the latter arm. Although he tested various modifications such as cut-away trigger guards, he seldom departed far from factory models except for sights and grips. Oversize grips and special front sights became the hallmarks of his personal handguns.

Three McGivern Colt Single-Actions include (top to bottom): .45 with S&W target sights and two .38 Specials with triggers taped. Center gun has slip hammer, while lower gun with smoothed hammer bears markings "Ed McGivern's Fanning Gun."

Three McGivern Colt Single-Actions include (top to bottom): .45 with S&W target sights and two .38 Specials with triggers taped. Center gun has slip hammer, while lower gun with smoothed hammer bears markings "Ed McGivern's Fanning Gun."

Nor did McGivern go for long-barrelled guns. His favorite barrel length was 4" or 6". A long barrel, while it made for a better sighting radius, slowed the draw. In caliber he favored the .38 Special as "the best all-round" and nearly all of his records were set with .38 Specials.

In a hypothetical shootout against a rifleman, he determined how far an experienced handgunner with a .38 Special might stand a 50/50 chance: 200 yds. When the .357 Magnum was developed, McGivern declared it a triumph of power and accuracy and promptly backed off his hypothetical opponent to 600 yds. Some of his .357 shooting at that range afforded the first confirmation of the new "powerhouse" among revolvers.

Nevertheless, McGivern was a firm believer in .22's for beginners. "Less noise, less recoil, less cost," he used to say. "The combination of recoil and noise throws the beginner off. The cost can scare him off."

To all handgunners, McGivern left a legacy in the form of his book Fast and Fancy Revolver Shooting, first published in 1938 and reissued in 1957 shortly before his death.

"Positive movements, properly controlled, correctly timed and accurately directed, form the basis of success in the fast and fancy revolver shooting field," McGivern declared. "The main thing is economy of movement and minimizing of motions. It is easier to move your finger one inch than two or three. Once you grasp the gun in the holster, don't shift your grip."

McGivern's hand demonstrates proper grip for double-action shooting with the revolver.

McGivern's hand demonstrates proper grip for double-action shooting with the revolver.

Like champions in every field of activity, McGivern kept fit at all times. Although bulky for his short height, he never was bulgy or greatly overweight.

"Body balance is one of the very vital factors governing well-placed hits in quickdraw shooting," McGivern wrote in The American Rifleman in June 1945. "Contrary to Western movies and Western story writers who insist on the 'gunman's crouch', on 'widespread legs' and on 'claw-like hands poised over holstered guns,' all stiff, cramped, awkward poses and all sprawling, strained positions of body, legs or arms are detrimental to results. Entirely aside from the fact that such actions would telegraph your intentions, they would materially slow up your own movements."

Pupil of McGivern's, Mrs. Bernice Peterson shot this whitetail at 45 yards with a .357 Magnum revolver in October, 1956. Her accomplishment made news in the Great Falls (Mont.) Tribune.

Pupil of McGivern's, Mrs. Bernice Peterson shot this whitetail at 45 yards with a .357 Magnum revolver in October, 1956. Her accomplishment made news in the Great Falls (Mont.) Tribune.

Fast, accurate handgunning, he wrote in another American Rifleman article, "depends to a very great extent upon the way the gun is handled the instant before and the instant after it leaves the holster." The gun should be grasped so that it lies and balances in the hand in relatively the same position as a normal shooting hold from start to finish.

At one point in perfecting a shoot-from-the-hip demonstration, McGivern is said to have burned up 3,500 rounds in short order. His enormous consumption of ammunition, especially for a man of moderate means, led some critics to doubt his whole standing.

Benefactor Identified

There are of course several explanations of how McGivern could afford to use up cases of cartridges and wear out revolver bores. One is that he received some help from manufacturers. Another, which time and The American Rifleman have verified, is that he had a particular "financial angel." Walter Groff, a wealthy Philadelphia Main Liner, was so intrigued by McGivern's impressive skill that he in effect grubstaked his shooting for years. Groff himself became the principal disciple and devotee of the McGivern system.

Thanks to Mrs. Walter Groff, the NRA Firearms Museum has become the resting place and showcase for 14 of Ed McGivern's choicest handguns and other memorabilia of the great little Montanan. Mrs. Groff presented them to the museum at the instance of NRA Life Member Henry M. Stewart, of Wynnewood, Pa., noted gun collector, in memory of Walter Groff. They may be seen in the museum today.

Memories Of McGivern: The Master From Montana

Former Army Air Corps Engineer recalls being instructed by the "fastest gun."

The commanding officer was fascinated with guns, especially pistols. As a second lieutenant commissioned directly from civilian life and posted as engineering officer to the B-17 bomber training base at Lewistown, Mont. in 1942, I was, of course, a rapt listener to the C. 0. when he spoke of any hobby interesting to him. It wasn't long before he mentioned his consuming preoccupation with pistols. He had a matched pair of S&W K22s, and since I had been familiar with guns most of my life, he found a willing listener.

The willing listener became quite excited when he told me that right in this small Montana town there lived one of the world's most fabulous masters of pistol shooting, especially rapid-fire work—none other than Ed McGivern, author of Fast And Fancy Revolver Shooting. I had stumbled onto his book in my hometown library several years before and was elated that I would have the chance to meet this author and famous pistol shot.

Though I concealed it, my first impression of Ed was disappointing. Probably around 60 years of age at the time, garbed in rumpled trousers, brilliantly colored shirt, nondescript cardigan and carpet slippers, he gave no evidence of romantic or spectacular ability with any type of weapon and certainly not anything as deadly as a six-gun.

Being only human he did brighten up a bit when he learned that I had read and re-read his book, marveling that any human could accomplish what the documented records showed he had done.

Elaborate timing device was a product of McGivern's own ingenuity. Providing measurements in increments down to 1/20 second, its accuracy was verified by the U.S. Bureau of Standards.

Elaborate timing device was a product of McGivern's own ingenuity. Providing measurements in increments down to 1/20 second, its accuracy was verified by the U.S. Bureau of Standards.

With a pixie-like quirk to his mouth he recounted to us how he had balanced a wooden safety match box on the back of his outstretched right hand, snatched for his holstered gun with the same hand while allowing the match box to fall freely, drawn his gun, fired, and demolished the box before it could reach the ground. All this with one hand! Again he told of using his right hand to throw into the air simultaneously five wooden blocks about 1 1/2" square then drawing his holstered gun with the same hand and shattering all five blocks.

As I recall, the first meeting with the C.O., Ed, and myself was given over to a general discussion of pistol shooting. After a few more visits to Ed's, there evolved from our talks tentative plans to form from some of the officers at the airbase a group for instruction in pistol shooting. Several were enthusiastic, although guns were something of a problem. Very few of us owned pistols and no issue revolvers in .22 caliber were available from ordnance. In my own case it was by extreme good fortune that I learned of a matched pair of H&R 2"-barrel revolvers fitted with adjustable sights and gold front beads owned by Ed and Mrs. McGivern. While Ed wouldn't part with his, some blandishment on his part convinced his good wife to sell hers to me, so I at least was armed for lessons under a real master of the art. By dint of scrounging, borrowing and what-not we managed to have some sort of handgun for each officer who was to participate. Ed even persuaded a local doctor friend of his to join our group to help with some of the teaching. He not only looked the part of a typical lean gun-slinger but was very fast with his revolver and deadly accurate to boot.

We needed the best possible instruction from both these individuals. Aside from the C.O. not one of the group could shoot a pistol for beans. One medical corps officer from Pennsylvania had never held a gun in his hand during his entire life. But we all got started one night.

We fired a few rounds at paper targets to whet the interest of those Ed felt might be lukewarm. Results were bad, as might be expected. Then we began to get what we'd come for; criticism from a master as to what we were doing wrong. Grip, stance, squeeze and all the fundamentals were drilled into us by Ed, sometimes with a caustic outburst at the evidence of monumental boobery on someone's part.

The first session didn't last long and gave no hint of the staggering supply of ammunition each one would need. Later Ed thought nothing of having each man expend 50 to 100 rounds at each nightly session, twice a week over a two-hour stretch.

We fired on paper targets to start. As we became more proficient Ed would generally limit our target perforating to what he termed "getting tuned in" with a few rounds. With his background of fast and fancy revolver shooting he had something else in mind. One of the first routines highly impressive to us was the business of cutting a playing card in half. While it did require a steady hand, we customarily shot at close range. We had the full length of the card to accommodate any error in elevation and had only to concentrate on the lateral placement of our shots. None of us realized at first, although of course Ed knew, that you don't stand directly in line with the card edge for this stunt. Rather the position is just slightly to one side. This serves to increase the target width by possibly 10 times over the bare thickness of the card itself. Even though the card isn't cut cleanly in two and is only about half separated, leaving a heavy black lead-smeared line for the balance of the width, it's still quite impressive.

Ed was also responsible for our introduction to "Poison Pete." Through a past assignment to train FBI personnel in defensive pistol shooting (as I got the story) Ed had the unshakable conviction that no mere target expert could truthfully be known as a master of the revolver. He claimed that one must know quick-draw, hip shooting, shooting with little warning and from unfavorable positions—and more —before he was truly an all-around pistol expert. He was also a firm believer in the competitive aspect of defense work. For this reason he rigged up a ludicrous life size dummy with threatening visage, curling black mustache, an old slouch hat, piercing eyes and—more to the point—a moveable right arm fabricated from gas pipe and swiveled at the shoulder so it would rise from the hand at hip position and simulate a gun arm rising in a drawing action. This action was produced by Ed standing out of sight behind the student and pulling a wire.

We were deadly serious about it. Each one would stand facing Poison Pete about 10 or 15 feet away, gun holstered, and when Pete's gun hand started to move without warning we were to draw, fire, and HIT. Ed had marked on the dummy those areas he considered critical zones where our bullets were to land.

One night, blue eyes twinkling, he told us we'd have no more trouble with Poison Pete because henceforth he would permit us to gang up on this tough hombre. Two of us instead of one were assigned to get Pete. But what Ed failed to tell us at first was that the two "good guys" would get only one effective shot—the first one. If I beat my partner to the draw and fired first— and missed—then his shot, no matter how squarely centered in Pete's black heart, didn't count. In this case our team was retired amidst jeers. Later only one was retired; either the one who fired last or the one who fired first and failed to hit a vital spot.

Ed had devised a spring-operated trap for throwing tin cans vertically into the air and when the Montana winter had moderated we held class outdoors. Ed would cock the trap, insert an empty gallon can, then pull the trip cord, and up it would sail. It looked large and slow and we were all quite embarrassed when no one hit it. Just about the time we were ready to give up the whole deal Ed admitted, with a chuckle, that he'd used this approach just to "build up our humility." Then he walked us over behind an old corral to a sort of gallows arrangement he had quietly rigged up the day before. With a cord threaded through the elevated pulley and attached to a can he could then pull the can up slowly, hold it momentarily, then let it fall, slowly. He explained that he was duplicating in slow motion the action of the can rising and falling when projected from the trap. In no time at all we were scoring hits on the can this way, usually at the preferred point in its trajectory—just as it reached the crest and started its downward descent. Having mastered the principle we had another go at the trap-projected gallon can with much better results. From gallon cans we went to quarts, then to soup cans and later to small milk cans. Not in one day, of course but over a period of time. Not one of the crew failed in due time to make good consistent scores on the small milk cans.

Our graduation from this phase of aerial shooting came when most of us were able to hit a penny thrown into the air. Not at every shot, and not everyone was able to make it, but most did. I still have my dented penny some 30 years later.

Our shooting was not all bloodless, however. One day we were shooting outdoors in the early summer. We killed a few paper targets "to get tuned in" as Ed was fond of saying, then went to card cutting. Ed broke into our routine and said, "All right, sports, you think you're getting pretty sharp, don't you? Let's see just how good you really are on a tough target."

To our amazement he pointed out an ordinary house fly crawling on the white paper background of our target frame and indicated that at least one of us ought to be able to hit it with a pistol! The C.O. raised his K-22, just started to aim, and was interrupted by Ed who suggested that any kind of a sportsman would give the game a decent chance by using not his own gun that he was familiar with, but another one. "Take the lieutenant's little 2" belly gun," Ed boomed, meaning mine.

The C.O. killed the fly at about 10 ft. with his second shot. Ed seemed pleased about the whole thing and I suppose he had a right to be. He taught me there was a lot more accuracy in that little short-barrel gun than I'd ever be able to get out of it until I was a lot better shot, as Ed so diplomatically put it. The gun is still a Stewart possession and I still think his conviction was entirely true.

Those of us who shot under Ed's tutelage so many times so many years ago will remember the old Army Air Corps. We'll remember the C.O., the hard winters, the B-17s which failed to return from routine training missions, the work, the responsibility, the crews who trained at this little satellite air base in Montana—not all of whom made it back from combat—and we'll remember something else. We'll remember Ed.

—Russell Stewart