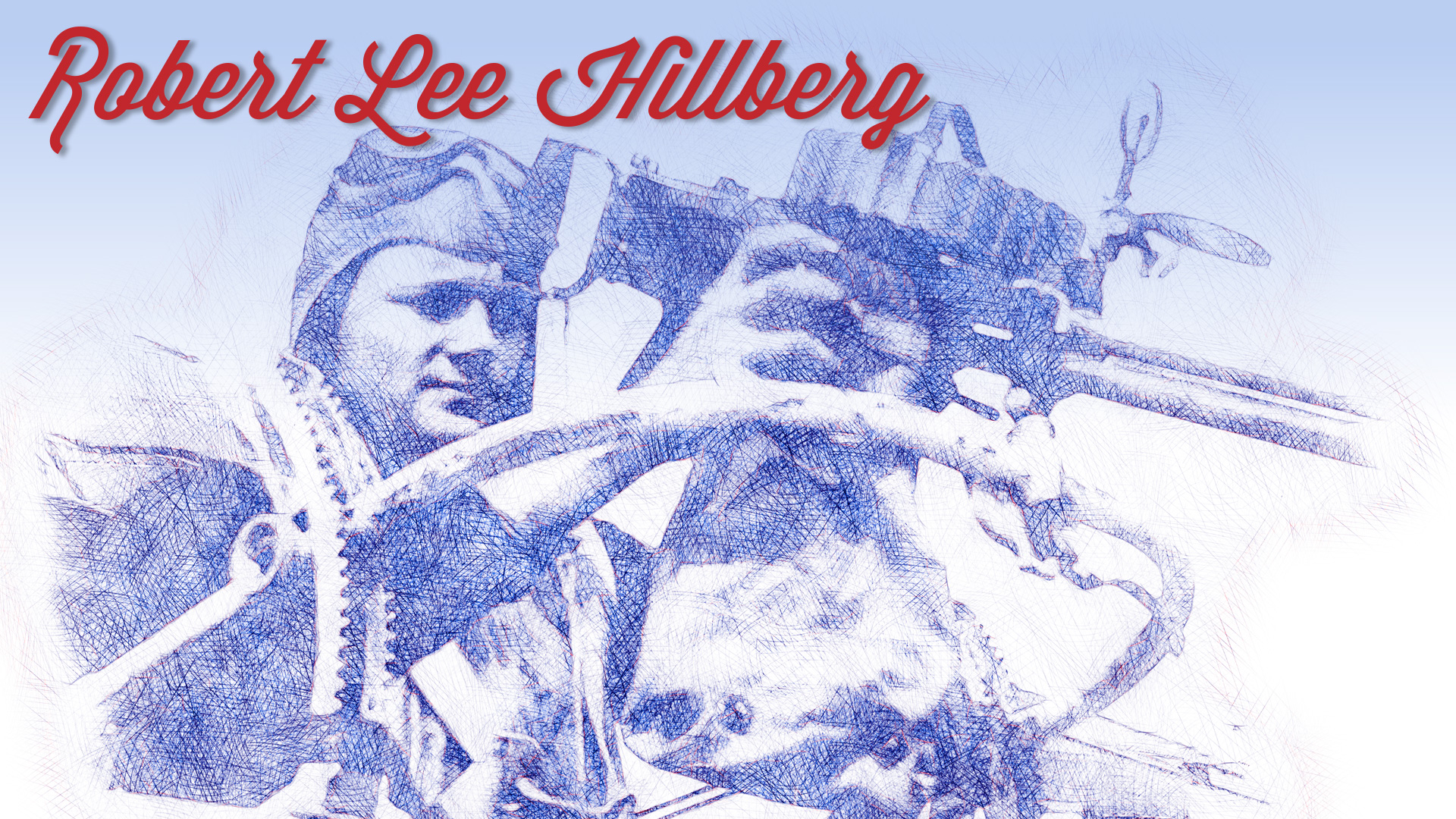

Unless you work in the firearm industry and are actually involved in the production of guns, you’ve probably never heard of the late Robert L. Hillberg. But he was not only one of the many men who designed and tested guns—working in the background and leaving others to receive the accolades for their achievements—he was one of the best.

Robert Lee Hillberg was born in Anamosa, Iowa, on Aug. 27, 1917. Growing up, he had a natural motivation toward everything mechanical and was particularly fascinated by the design of firearms. After several years of studying and collecting all types of firearms, he designed a .38-cal. machine gun. Then, while serving as a reserve member of Squadron VN11RD-9, at the U. S. Naval Air Base, Wold-Chamberlain Field in 1937, Hillberg built a working prototype. The following year, he went to Colt’s Patent Firearms in Hartford, Conn., in the hopes of selling the design. He demonstrated the prototype, but the famed company ultimately decided it was not interested in Hillberg’s gun—but it was interested in him. Colt extended a job offer, and Hillberg eventually worked there in various roles, including engineering, assembly, inspection and manufacturing. In fact, while at Colt, Hillberg designed a short version of the company’s Single Action Army revolver along with a 7/8-scale, .22 Long Rifle-chambered version of the Colt Frontier, which the company went on to produce years later.

After two years at Colt, Hillberg saw more opportunities to advance his career in the airline industry. He accepted a better-paying job with Pratt & Whitney Aircraft. While there, he began development of an aircraft cannon. He later accepted a job with the Ordnance Division of Bell Aircraft and, after several years at Bell, he moved on to Republic Aviation. It was there that he became the F-92 armament unit leader and engaged in the “Secret Room” as an armament consultant for advanced fighter aircraft. However, despite the fact that the money and opportunities in the aircraft industry were great, Hillberg’s heart remained in firearm design.

In 1951, he was hired by High Standard Mfg. Co. as head of research and development. He designed the T-152 tank machine gun, a .22-cal. semi-automatic sporting rifle and one of the earliest commercial, semi-automatic, gas-operated shotguns: the Model 60. High Standard had a model shop for fabricating designs into working prototypes, and most of the modelmakers worked in the civilian/commercial end of the business yet also handled the model fabrication for military test projects. The answer to this problem was to contract the military jobs out. The Bellmore Johnson Tool Co. had produced parts for a recent military machine gun project, which Hillberg ran. Bellmore Johnson, located in Hamden, Conn., was also a source for specialty tools for the firearm industry, and it employed the best modelmakers in the business. It was also a leading producer of experimental-model firearms for various manufacturers including Winchester, Marlin, Mossberg, Colt and High Standard.

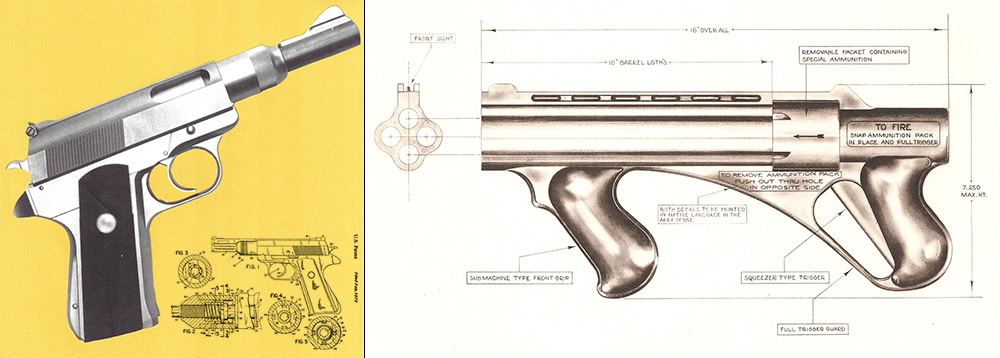

Even with his busy work schedule at High Standard, Hillberg found time for a personal project—a pistol with one main frame, capable of firing three different chamberings: the Tri-Matic. Hillberg’s design had a streamlined, space-age profile that eventually morphed into what later became one of the most iconic pistols of all time. He presented his drawings and production ideas to High Standard’s management, but the company already had a line of top-selling .22 pistols, and management was not receptive to Hillberg’s proposal. So, Hillberg showed his drawings to Howard Johnson, one of the owners of Bellmore Johnson, who was impressed and convinced Hillberg to resign from High Standard and come to work for the company. Hillberg agreed, relocating to Bellmore Johnson as chief engineer and moving into a small office in Cheshire, Conn. Along with other members of Bellmore Johnson, Hillberg formed Whitney Firearms, Inc. with the goal to produce and market the .22-cal. pistol of his own design: the Whitney Wolverine. The venture was short-lived, with only 10,000 of the pistols being produced before Whitney Firearms, Inc. went into bankruptcy in 1957.

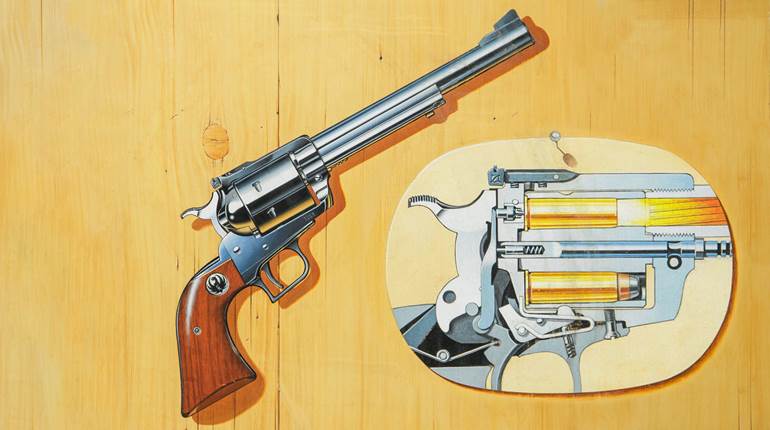

From 1957 to 1980, Hillberg remained as Bellmore Johnson’s chief engineer, with the company’s customers including about every major firearm company in the United States—along with several confidential firearm contracts associated with the military. His designs while at Bellmore Johnson ranged from handguns to shotguns, both combat and sporting, and rifles. In this capacity, Hillberg also conducted business as a gun consultant and designer for the firearm industry. A listing of the customers he served reads like a who’s who of the industry: Browning Arms; Colt; High Standard; Winchester; Marlin Firearms; O.F. Mossberg & Sons; Remington Arms; Savage Arms; Ithaca Gun Co.; and the Springfield Armory. Hillberg is also credited with a raft of commercial and military firearm designs, including:

T-152 tank machine gun (Tank Arsenal, Springfield Armory)

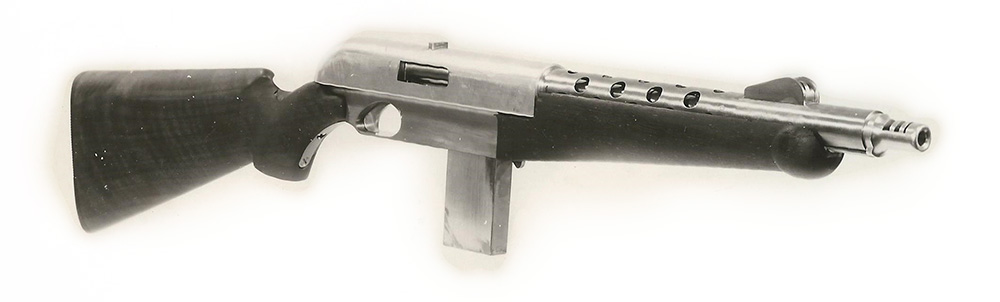

9 mm Luger submachine gun

.223 Rem. M1 carbine (CIA)

.22 Long Rifle conversion for M16 rifle

12-ga. police riot pump shotgun

Four-barrel military & police riot shotgun

Eight-barrel military & police combination tear gas riot shotgun

.38-cal. pocket-size revolver (Colt)

Four-shot tear gas & .22-cal. pocket pistol (Colt)

.22-cal. family line sporting pistol (Colt)

Low-cost plinking pistol (High Standard)

Single-shot .22 Western-style revolver (Savage)

Single-shot simulated Winchester 94 boys rifle (Ithaca)

Single-shot shotgun (Ithaca)

Single-shot shotgun (Savage)

Low-cost semi-automatic shotgun (Savage)

.357 Mag./.22-cal. revolver (Browning)

Over-under high-power rifle (Browning)

Pump-action shotgun (Browning Model BPS)

.357 Mag./.22-cal. revolver (Winchester)

Cattle stun gun (Winchester)

.45-70 Gov’t lever-action rifle (Marlin)

Sharps high-power rifle (Colt)

12-ga. semi-automatic shotgun (Marlin)

Compact off-duty police handgun, .357-cal. four-barrel (COP, Inc.)

Ring airfoil missile launcher (Government)

.22-cal. semi-automatic pistol (Whitney)

Folding shotgun stock (Remington)

.45-cal. semi-automatic pistol (Wildey)

He is also the listed patent holder for more than 40 U.S. firearm innovations, including the following: (most of the dates listed are for the time the patent was issued—some were applied for much earlier)

176516 – Pistol – 1956

2842885 – Firing pin with plastic sleeve (High Standard) – 1958

2845001 – Manual charger – 1958

2909101 – Gas operated firearm with gas piston surrounding a tubular magazine (High Standard) – 1959

3621596 – Firearm with falling breech block – 1959

3060810 – Sear mechanism disconnected by breech block motion – 1962

263413 – Handgun (COP Inc.) – 1974

3260009 – Multi-barrel firearm with rotatable and reciprocable hammer (Olin Mathieson Corp.) – 1966

3546417 – Shotgun barrel construction (Bellmore Johnson Tool Co.) – 1970

3621596 – Firearm with falling breech block (Colt) – 1971

3651594 – Shotgun barrel construction – 1972

3798819 – Folding gun stock – 1974

3810326 – Construction for revolver (Browning) – 1974

3988849 – Handgun signal launcher – 1976

4141164 – Magazine isolator for pump shotgun (Browning) – 1979

4221066 – Firearm grip assembly (Wildey) – filed 1974

4208947 – Firearm hammer block safety mechanism (Wildey) – filed 1974

4291481 – Firearm magazine safety mechanism (Wildey) – filed 1974

262567 – Rifle design – 1982

4400900 – Multi-barrel handgun firing mechanism – 1983

4416078 – Handgun strut assembly – 1983

4424638 – Handgun – 1984

After retiring from Bellmore Johnson, Hillberg continued to serve as a firearm expert witness, for both plaintiffs and defendants. His expertise pertained to anything connected to firearms, with a special interest in cases that involved the testing and safety of firearm designs. He was also a retired deputy sheriff and a member of several police organizations, including: the New England Ass’n of Chiefs of Police; the Intl. Ass’n of Chiefs of Police; the American Law Enforcement Officers Ass’n; the New Haven County Sheriffs Ass’n; the National Sheriffs Ass’n; and the Connecticut Chiefs of Police Ass’n (firearms committee).

Robert Lee Hillberg died Aug. 12, 2012, at 94. He was predeceased by his wife, Jeanette, and is survived by his son, Lee. His career had spanned from before World War II into the 21st century and continues to influence the firearm industry to this day. When asked what design accomplishment he was most proud of, he was quick to answer: “The Whitney Wolverine.”

The below letter, sent by Hillberg, appeared originally in The American Rifleman in "Dope Bag" of June 1966.

Editor:

The golden era of firearms design was at the turn of the century. Men like von Mannlicher, Paul Mauser, Andreas Schwarzlose, John Browning, and others pioneered the art so thoroughly that virtually nothing new in basic firearms design has been developed since. The heritage of every modern design, both military and commercial, can be traced back to the creative genius of a small group of designers some 60 years ago.

The firearms industry of today has certainly made tremendous inroads in the improvement of design, the efficiency of production, and the perfection of materials and processes. The competitive future of a company in business today vitally depends on this. ·

From an individual design point of view, the present firearms designer will concentrate mostly on the perfection of older basic designs. His main efforts will be directed toward less direct labor or reduced manufacturing cost. Gone are the days of an individual craftsman applying a high degree of skilled hand labor on high production, domestically manufactured guns. The few rare exceptions are factory prestige items made only in limited quantities at a premium price. Of secondary importance to the designer is -the perfection of the weapon for performance and durability. In the field of military arms design, the order of importance would be performance, durability, and cost.

To the novice designer, this does not present a very attractive picture as opportunities for individual expression in the hallowed field of radical departure from today's basic concepts are practically nonexistent. The highly competitive position of today's modern firearms manufacturers by economic necessity must place the engineering scope in this priority.

This, of course, does not include such exotic developments as the laser, liquid propellants, rocket projectiles, self-disintegrating ammunition cases, and special purpose developments. The development of these "way out" designs is beyond the practical reach of an individual designer. If these products are 'around the corner' they will be perfected only through the team efforts of many specialists in the fields of chemistry, electronics, physics, hydraulics, and engineering. For the most part, the gun industry participates very little in this area. There are only 2 firearms companies in the business who have the highly skilled technical personnel and the research facilities necessary to carry out these programs. In almost every instance the government sponsors these programs with research and development contracts.

Non-Firearms Manufacturers

A major part of these programs is carried out by non-firearms manufacturers such as research organizations or large industries possessing the necessary technical personnel and facilities.

The participation of a young man in such a program as this makes a college education in his chosen technical field mandatory.

What, then, is left for the future Mauser or Browning in the firearms business? The answer, I'm afraid, is not too glamorous. The industry offers a tremendous opportunity and challenge for tool designers, processing and planning, etc., but a very limited future for the pure-bred product designer. Actually, today's needs are dictated by the sales department and market research. The product objectives, once established, are solved in routine design procedure. The encompassing objectives leave little room for true pure design imagination. The real secret of today's designers is the ability to meet the product objectives with 'the least possible manufacturing cost. From this we can readily deduce that a firearms development engineer must have a complete background in engineering, modern processing, materials, and costing. These requirements are important because the over-all value of the design to a given company is whether or not the product can be built at a low enough cost with a reasonable profit to allow sales to market it at a low enough price to be competitive with adequate volume.

This is equally true whether the product is selling in the low or high cost bracket since few companies, if any, care to market even a high price quality product at a loss for prestige reasons. It is very important for the independent designer when submitting a new product to a company for consideration that he is also equipped with a processing and cost study, as well as complete detailed drawings. If the pocket-book will afford it, a working model is a great stride toward selling the design.

The education requirements for the designer, as stated previously, should be augmented by other attributes. While secondary in importance, they are nonetheless extremely desirable. These would include a broad background in firearms technical history, a creative mind, and good draftsmanship ability.

This is today's firearms designer. Unfortunately, the exacting demands required are not compensated by. today's rewards. The basic reason for this is the relatively restricted role imposed by today's manufacturers. From a pure design point of view only, my advice to a young man with these attributes would be to lend his talents to the automotive, aircraft, missile, or other industry where the monetary rewards are much higher and the limits of a fertile imagination are Jess restricted.

This applies to design genius only. Today's firearms industry needs top technical help in all other phases. If giving the public a better gun for the same money, or the same gun for less money, is your destiny, the gun industry will welcome you with open arms. If being a part of a team to produce this gun or to merchandise it is your aim, there is a place for you in the industry. If your burning ambition is to design a new gun and get rich–forget it."