Like Bill Jordan, Combs favored the Model 19 Smith & Wesson .357 Mag. with a 4" barrel as the best all-around handgun/cartridge choice for the majority of peace officers.

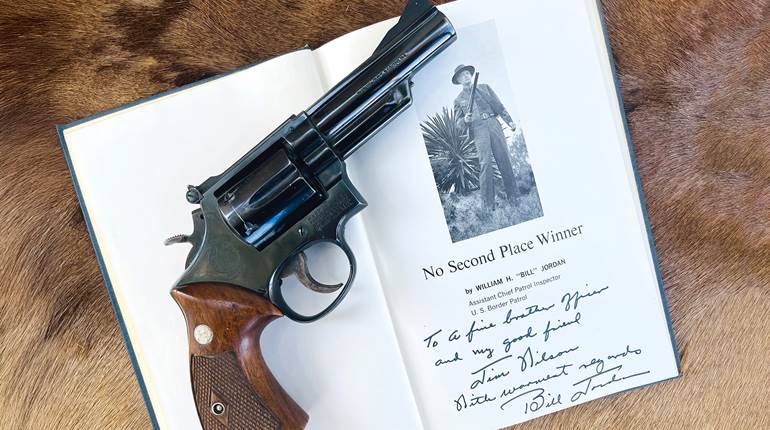

After I came to know Captain Dan Combs of the Oklahoma Highway Patrol in the mid-1960s, we often would meet at my motel during my visits to Oklahoma City,” explained former Border Patrol assistant chief, legendary pistol shooter and author Bill Jordan (1911-1997). “We’d both unload and holster our Smith & Wesson Combat Magnum revolvers and then get ready and turn on the television set. Whenever the picture would change, we’d draw and snap at the image. I won’t say which one of us usually won this contest, but if I had known Captain Combs when I was writing my book No Second Place Winner, I would have included a chapter about him and his gun-handling expertise.”

That is fitting praise from Jordan who, during his career was recorded drawing, firing and hitting his target in 0.27 of a second with a double-action revolver.

Combs and Jordan were among a handful of elite law enforcement exhibition shooters active after World War II. This included Jacob Aldolphus “Jelly” Bryce (November 2017, p. 60). Bryce was an FBI agent of the 1930s who was formerly with the Oklahoma City Police Dept. Unlike Combs and Jordan who favored the K-frame-size .357 Mag. revolvers, Bryce favored the early .38-44 Outdoorsman on the larger N-frame. He also shot that frame size Smith & Wesson in .357 Mag. and .44 Spl. While each of their styles varied, all were blessed with excellent eyesight and coordination that most people simply don’t possess.

They occasionally shot together in Oklahoma City. All three were in the category of the low-sub-second draw, earning them the labels “before you can blink” and “hit what you point at.” What a day at the range that must have been.

Much of Jordan’s exhibition shooting was, by necessity, done indoors with wax bullets. Much of Bryce’s shooting expertise was usually limited to an FBI audience but also included some unlucky gangsters.

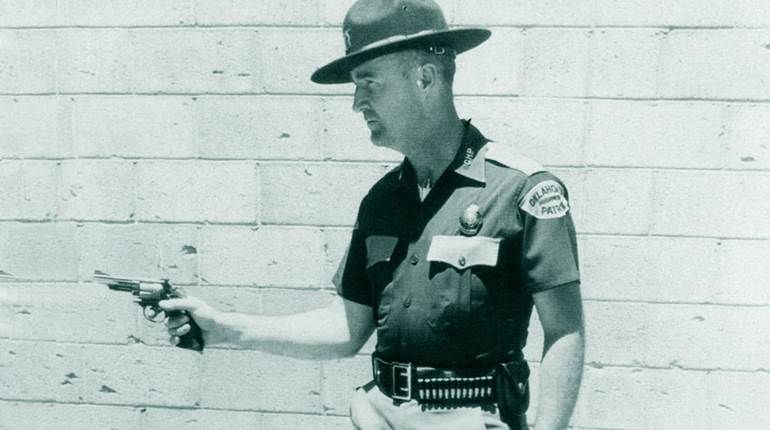

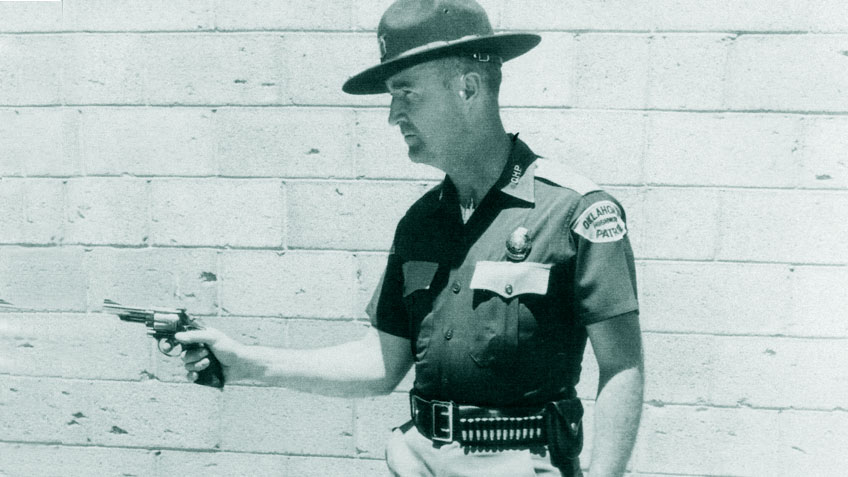

On the other hand, Combs was often introduced during his very public exhibitions as “the pride of the Oklahoma Highway Patrol,” and performed more than 3,000 shooting demonstrations—most of them outdoors with live ammunition. Audiences ranged from soldiers stationed at Fort Sill, Okla., to fellow law officers to youth organizations such as the Boy Scouts. He helped define the outer limits of just how good a person can become with a firearm.

His exhibitions included: quick-draw and speed-shooting with one and two double-action revolvers, speed fanning of Colt and Ruger single-action revolvers, along with demonstrations of his skill with rifles, shotguns and machine guns.

Using what he termed his “homespun cotton-patch philosophy,” Combs tied his demonstrations to lectures on firearm and traffic safety. By drawing a parallel between a traffic violator and a criminal with a gun, Combs tried to improve the awareness for defensive driving.

“A drunk driver is 10 times more dangerous to the public’s well being than a felon brandishing a pistol or rifle,” Combs used to tell his standing-room-only audiences. “While a fellow may kill one or two people before someone nails him, the drunk driver can, and often does, kill a car full of innocent citizens. Keep your mind on your business, whether you are driving a car or handling a gun.”

He fascinated audiences with firearms skill that included throwing six clay pigeons into the air with one hand and then busting all of them mid-air with a Remington 1100 shotgun. Using his .30-’06 Sprg. Remington semi-automatic rifle, he could consistently vaporize grapes thrown into the air by an assistant.

Watching a film of a typical Combs performance of the early 1970s shows a man comfortable with a variety of firearms. He remains among the few people who could empty a 50-round drum from a .45 ACP-chambered Thompson submachine gun into a playing card in one long burst. His ability to control a gun under recoil was so great that he could empty an M14 rifle’s 20-round magazine into the head of a target silhouette at 20 paces in one short and continuous burst with the hard-recoiling .308 Win. cartridge. Ambidextrous, Combs could perform his rifle and shotgun trickshots from either shoulder.

For his handgun demonstrations, Combs would fascinate audiences with his ability to lay an empty cartridge box on top of his right hand poised for a draw. At a signal, he would draw his handgun and bounce the cardboard box in the air and quick finger a shot into the box that sent it flying. He prefaced his public gun-handling sessions by saying: “I am the worst shot and the slowest draw in the entire Oklahoma Highway Patrol. The commissioner ordered me to perform these exhibitions so I can become as good with a handgun as the rest of the troopers.”

For his demonstrations, he used a variety of handguns. Much of the time, he used an unmodified Model 15 Combat Masterpiece in .38 Spl. that was issued to the Oklahoma Highway Patrol in the late 1950s and early 1960s, though he favored the Model 19 Smith & Wesson Combat Magnum with a 4" barrel. Combs believed the Model 19, with its relatively small and light (at 36 ozs., it was the lightest magnum at the time) frame size, coupled with the power of the .357 Mag. cartridge, made a perfect combination for a police officer. He was a primary force in the Oklahoma Highway Patrol’s decision to abandon the .38 Spl. and the subsequent issue of the Smith & Wesson .357 Mag. revolvers to troopers in the early 1970s.

In single-action revolvers, Combs was well aware of the mystique of the Colt, and did use them in his early demonstrations. He soon switched to a pair of Ruger Blackhawks in .357 Mag. because of the Blackhawk’s stout internal mechanism.

“As a firearms instructor for the patrol, I hope and pray that neither myself nor one of my student officers will ever have to use our guns,” explained Combs to a group of lawmen as he was recorded for a training film of the early 1970s. “But, I don’t want to think about being second in a gun fight. There is only one winner, and a funeral for the runner up.”

He preferred his handgun grips unmodified with original factory stocks. Although he disliked checkering on the stocks, he didn’t bother to sand or file them smooth. Rather, Combs smoothed them by simply practicing his draws a few hundred thousand times, which slowly smoothed the roughest of checkering. He practiced his draw and other gun-handling skills with the same discipline a dedicated athlete prepares for competition. For his demonstrations, Combs developed a steel-lined, straight-drop holster to aid speed drawing. He always warned people viewing his demonstrations that fast-draw was “tricky and can be dangerous.”

A farm boy raised in Garvin County, Okla., Combs spent much of his youth on horseback punching cattle and picking cotton. He also learned how to shoot. By the age of 10, he could consistently hit walnut-size aerial targets with his single-shot .22 rifle. The 1930s-era depression helped shape his personality and character. According to those closest to him, Combs used this early adversity to teach himself both the toughness and understanding needed later in life as a professional lawman.

A veteran of combat with the U.S. Army in the southwest Pacific, Combs returned at the end of World War II to begin his law enforcement career with the Shawnee, Okla., Police Dept. He joined the Oklahoma Highway Patrol three years later, and he soon perfected his fast-draw—as a hobby and as a skill he felt might be required for his survival. Combs’ talents were recognized, and he soon became a firearm instructor in the training division of the Oklahoma Department of Public Safety.

“He possessed the fastest reflexes and the best eye-to-hand coordination of anyone I have ever seen,” said Dutch Schneider, a retired Oklahoma Highway Patrol officer when interviewed about Combs in 1990. Schneider was Combs’ partner in the training section during the 1970s. “Dan practiced daily and trained thousands of other law officers from a variety of agencies on how to best use their sidearms. Particularly with a rookie just learning the rudiments of shooting and safe gun handling, Dan had infinite patience and understanding.” Over the years, several Highway Patrol Troopers personally thanked Combs for teaching them the skills that saved their lives in gunfights.

Combs’ fast-draw/quick-shoot demonstrations at the NRA National Pistol Shooting Championships soon brought various police agency representatives and firearm instructors to Oklahoma City to study the officer’s unique skills.

“Some people think it is silly practicing fast-draw,” explained Combs to a newspaper reporter during the 1960s. “They think you’re playing cowboy and outlaw. Heck, I’m just practicing to help me stay alive. The reason, besides demonstration, that I practice fast-draw is to possibly prevent someone from killing me, a fellow patrolman or a citizen.”

A well-built, athletic man just less than six feet tall, Combs was a lifetime NRA supporter and firm believer in the right to keep and bear arms. “I speak only as one peace officer, but we must never, ever disarm the American public,” he warned at the end of one of his demonstrations.

Combs was severely wounded by, but survived the accidental discharge of, a .45-cal. semi-automatic handgun at the range during the late 1960s. He resumed his training and exhibition schedule in the early 1970s.

Well-liked by fellow officers, Combs prematurely died at age 55 at his home of a heart attack during the early morning hours of Feb. 21, 1976. Honor guards from the Oklahoma City and Tulsa police departments, as well as his companions from the Oklahoma Highway Patrol, stood in silent tribute to Capt. Combs, Badge Number 14.

Combs remains missed. Just prior to his death, Combs actively promoted the use of bulletproof vests for his “boys” in the Highway Patrol. He was one of the early pivotal law enforcement professionals who began increasing officer awareness of survival training, which is now commonplace across the country. His realistic law enforcement training emphasized surviving a quickly occurring confrontation at close range.

“Combs developed our early handgun training and qualification course,” said Capt. Chris West, Public Affairs Commander with the Oklahoma Highway Patrol. “Although we do not still use the same course he developed, his legacy lives on in our rich tradition and history. I wish I had known him.”

In his memory, a glass cabinet near the entrance of the Oklahoma Highway Patrol Academy in Oklahoma City holds Combs’ Thompson submachine gun and several revolvers, along with pictures, trophies and shooting mementos that represent one man’s dedication to the shooting art and his passion of teaching it to fellow law enforcement officers.

Keith R. Schmidt is a sergeant and firearm instructor assigned to the training division of the Harris County Department Reserves, Houston, Texas.