The Henry Repeating Arms Co. has built a market around its ability to combine historic connections and traditional aesthetics with highly functional, American-made products. And the Big Boy revolvers built on its first “conventional” handgun platform—it already offered “mare’s leg” pistol versions of its rimfire and centerfire lever-action rifles—demonstrate this knack at blending heritage and modernity even further. Make no mistake, while tipping its hat to historical handguns on the outside, the Big Boy is a thoroughly modern wheelgun on the inside with performance that is anything other than antiquated.

The revolver is offered in two models, with all basic specifications the same, save for the grip profile and slightly different overall weights and height/length dimensions. A rounded-to-a-point “Birdshead” grip is offered on one model and a hand-filling, square-butt “Gunfighter” grip is on the second. Like other Henry products, the Big Boy revolvers’ unique appearance is likely what you’ll notice first. The shared main frame and trigger guard profile seem to combine Colt’s 19th-century Model 1878 with its 20th-century Trooper. In a nod to classic double-action service handguns like the Trooper, Henry reminds us that a magnum revolver doesn’t need to have a vent rib or a full-length underlug.

The Birdshead grip approximates that of the full-size Colt 1878 versus the more diminutive 1877 Lighting, and the lower portion of the Gunfighter grip is nearly identical in size and profile to a Colt 1860 Army. On the back end, the frame is rounded to match the arch of the hammer, which comes straight from the 1878, with an extended “beavertail” spur at the top of the backstrap—a feature found on both Colt and Smith & Wesson revolvers from the 1870s. On the front end, both revolvers’ 4" heavy-profile round barrel is recessed on the bottom to accommodate the head of the unsupported ejector rod.

The materials and finish used on the Big Boy revolvers are also old-school. Steel parts are finished with a high-polish blue, and the brass is also highly polished. Henry knows the place that brass holds in traditional firearm construction, as demonstrated with its lever-action rifles. That material finds its appropriate place in the one-piece trigger guard and grip frame on both models just as it did on many early six-shooters. Stocks are smooth-finished American walnut that have a thumb rest on each side to accommodate both right- and left-handed shooters.

On the mechanical side of things, the Big Boy revolver platform features a solid frame with a six-shot cylinder that rotates counterclockwise and swings out to the left, using a forward-sliding cylinder release positioned on the left side of the frame. With the cylinder out, ejection is accomplished by actuating a rod that pushes the extractor. When the action is closed, the cylinder locks into the frame with a stop at the rear, while a ball detent locks the crane into the frame at the front.

A double-action with a swing-out cylinder might not seem like the first choice for a “traditional” revolver, but the double-action trigger mechanism is as old as revolvers themselves. In 1851, as Samuel Colt was perfecting the form of his cap-and-ball six-shooter, Englishman Robert Adams was patenting a double-action wheelgun (Colt had experimented with and abandoned his own double-action designs). During the Civil War, double-action Adams, Kerr, Starr, Pettengill and Remington revolvers served alongside the more famous single-action designs. Throughout the frontier era, “self-cocking” revolvers by Colt, Merwin Hulbert and Smith & Wesson held their place with their manually cocked contemporaries. And the swing-out cylinder? Colt introduced that design in 1889.

The Big Boy revolvers’ double-action trigger mechanism features a hammer with an exposed spur that can be used for cocking in single-action mode. Safety is provided by a transfer bar that only allows the hammer to strike the frame-mounted firing pin when the trigger has been fully pressed. No need to leave an empty chamber under the hammer here. The hammer is powered by a coil-type mainspring. For durability, the spring is housed in an extension of the steel frame that fits within the brass grip frame.

Though Henry refers to the Big Boy frame as “medium-sized,” the revolvers’ dimensions are closer to that of “medium-large”-frame handguns such as a Smith & Wesson L-frame or a Colt J-frame. The cylinder of the Big Boy has a diameter of 1.56", and the frame’s topstrap has a width of 0.68" and is 0.23" thick. The barrel has a diameter of 0.75" where it meets the frame and tapers slightly to 0.70" at the muzzle. Weighing 35 ozs. with the Gunfighter grip or just about two ounces less for the Birdshead grip model—which measures only 0.02" less in overall height and 0.37" less in overall length—the result is an “outdoorsman” or “service-size” revolver that is designed to be worn on the belt in a sturdy holster.

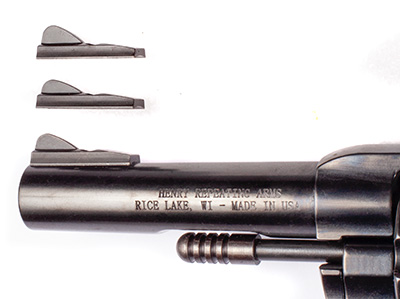

While the Big Boy sights are fixed, they can be adjusted with no filing required. The front sight blade is on a ramp that attaches to the barrel with a screw. Henry supplies each revolver with three clearly marked front sights of “high,” “medium” and “low” heights to allow the owner to converge the point of aim with the point of impact. The 0.06"-wide front sight blade nestles in the rear sight “gutter” on the frame’s topstrap that pinches smaller at the rear, for a classic revolver sight picture.

On the range, the Big Boy revolvers proved their function could match their form. The smooth-faced trigger on both revolvers was excellent. The double-action trigger pull is smooth throughout its arc before breaking cleanly at 10 lbs., 12 ozs., for the Gunfighter model and 9 lbs., 7 ozs., for the Birdshead. In single-action mode, the trigger on both revolvers broke crisply with no perceivable take-up or overtravel, requiring 2 lbs., 12 ozs., of force to drop the hammer. The narrow hammer spur is low enough to not obscure a full sight picture when it is at rest, yet its deep grooves give a sure purchase for placing the mechanism in single-action mode.

Shooting the Big Boy is a balancing act between its excellent trigger and basic sights. Though the revolver’s sights are regulated for a center-hold point of aim, for more precision shooting, I nestled the minimal sight picture on the six-o’clock position of the target’s bullseye. Five-shot groups at 15 yards, fired from a rested bench position, averaged 1.93", with the .357 Mag. groups typically having two or three of their five shots touching.

Both revolvers came with the medium-height front sight installed, but I needed to change to the low-height sight to get the cartridges we tested, from the lightest .38 Spl. to the heaviest .357s, to impact at the point of aim at 15 yards. Both .38 Spl. and .357 Mag. loads had a tendency to shoot about 1" to the right at that range. The front sight interchanges easily and stays tight, even during a long session of magnum recoil. With the easy interchangeability of the front sight, I hope that the aftermarket will soon provide an option for the Big Boy with a small brass bead or (traditionalists, close your eyes) a fiber-optic insert.

The Big Boy’s 4" barrel length is on the minimal end of achieving the .357 Mag. cartridge’s full ballistic potential, with Remington’s Performance Wheelgun loads capped with a classic 158-grain lead semi-wadcutter bullet averaging just shy of 1,200 f.p.s. and 500 ft.-lbs. of energy at the muzzle. At just about 2 lbs., the Big Boy revolver’s heft is enough to soak up the recoil of the stoutest magnum loads and makes .38 Spl. plinking rounds enjoyable for even the most recoil-shy shooter. While the Gunfighter grip gives a full-handed purchase, magnum recoil was also quite manageable with the Birdshead grip. Despite its pocket-revolver profile, it is full-size in the vein of the Model 1878.

Each Big Boy revolver functioned perfectly from both the bench and in the field. The ejector rod’s stroke moves empty cases, even .38 Spl., just to the edge of the cylinder without pushing them clear. For some wheelgun aficionados, this is perfect, as the extractor can’t push past the cases to allow them to slip back into the cylinder and induce a jam. Tipping the rear of the cylinder downward while working the ejector rod easily cleared empties, even after fouling starts to build up in the revolver’s chambers.

Cleaning the Big Boy revolver is made easier by Henry’s cylinder-removal system. Pushing up on a small, serrated button located in the top front of the trigger guard allows for the cylinder and crane assembly to be removed from the frame as a unit. Not only is it infinitely easier to clean a revolver when the cylinder is separated from the frame, but this method of easy cylinder removal could allow Henry to offer versions of the Big Boy that would accommodate alternate chamberings by swapping cylinders. Removing the stocks provides access to the mainspring assembly. And that is as far as Henry recommends going for normal maintenance and cleaning. The rest of the revolver’s internals are located under a sideplate on the right of the frame.

While Henry lists the “best uses” of the Big Boy revolver as “target/collector,” I would add “close-range hunting” and “self-defense.” Even with its minimal sights, the Big Boy certainly has the accuracy to take game within the limitations of the ballistics provided by its 4" barrel. Its swing-out cylinder allows for rapid reloads with a speed-loading device (use those intended for a S&W L-frame or Ruger GP100) and its weight and smooth double-action trigger meant that its cylinder could be emptied with speed into a target at anti-social distances. While it’s bigger than what most people would want to carry concealed, the Big Boy’s size mimics the service revolvers that American law enforcement carried daily for nearly a century. It would be ideal as a home-defense revolver or carried in a good belt rig when outdoors. The bob-tailed grip of the Birdshead model carries nicely in a chest-mounted holster.

Anticipating that the Big Boy will be as popular as other Henry products, manufacturers including DeSantis, Diamond D Custom and Simply Rugged have already stepped in with holsters specifically designed to fit the new revolver. To customize your revolver’s appearance, Henry offers accessory stocks in laminated wood, engineered cocobolo or checkered walnut. Expect other manufacturers of holsters, stocks and sights to follow the company’s lead.

With an MSRP of $928, the Big Boy is comparable in price to similar models offered by fellow American wheelgun manufacturers Colt, Ruger and Smith & Wesson, reflecting the economic realities of high-polished blued steel and walnut that is “Made in America, or Not Made at All.” A discussion of price brings up a few minor quibbles with the Big Boy’s appearance. While metal and wood fit was excellent, in some areas it looked like the metal could have used some additional polishing before the bluing process, with parts such as the trigger and hammer having visible mold marks.

Underneath that old-time veneer, Henry has included some features that give its Big Boy revolver family room to grow. The manual supplied with the .357 models makes it clear that 10-shot .22 Long Rifle and .22 WMR Big Boys are on the way. It would be interesting to see if Henry could use this size frame for other cartridges that it offers rifles in, such as a seven-shot .327 Fed. Mag. or a five-shot .41 Mag., .44-40 Win., .44 Spl. or .45 Colt. And while we’re talking about companions for the company’s long guns, how about interchangeable cylinders for semi-automatic pistol cartridges? (Asking for a Homesteader.)

With the Big Boy, Henry is making a revolver that has traditional aesthetics, but carries the technology under the hood to compete with the latest wheelgun designs on the market. In this way, Henry has once again “reverse-engineered” history to provide heritage in its most practical form.