Image: 1953 Springfield Armory Garand

This article was first published in American Rifleman, August 2006

The best battle implement ever devised.” This oft-repeated praise from Gen. George S. Patton summed up his feelings about the “U.S. Rifle, Cal. .30, M1.” Popularly known as the “Garand” after its inventor, Springfield Armory employee John C. Garand, the M1 garnered a well-deserved reputation as the finest general-issue military rifle of World War II. While several other nations, including Germany and the Soviet Union, fielded some semi-automatic and selective-fire rifles during the war, the United States was the only nation to arm its military primarily with a semi-automatic service rifle. When World War II ended in 1945, the M1 Garand was firmly entrenched as America’s standard service rifle.

After the war’s end, outstanding production contracts were cancelled on most military arms, including the M1, because there were ample numbers on hand to satisfy demand for the foreseeable future. From late 1945 until 1950, the Ordnance Department shifted its focus from the procurement of new guns to rebuilding and refurbishing the vast quantities left over from the war. During that period, a number of ordnance facilities rebuilt large numbers of all types of military small arms, including M1 rifles. For example, Springfield Armory manufactured 331,854 new M1 barrels between fiscal years 1946 and 1947 for use in overhauling existing Garands. The armory manufactured large quantities of most M1 rifle parts, excluding receivers, for replacement purposes from 1946 until the very early 1950s.

The typical post-World War II arsenal overhaul procedure consisted of replacing worn, broken or superseded parts with newly made replacement components or serviceable parts salvaged from other rifles.

The outbreak of hostilities on the Korean peninsula in 1950 renewed demand for small arms, including M1 rifles. Even with the large stockpile of World War II arms (overhauled and otherwise), the scale of the Korean War depleted supplies. To address the demand, Springfield Armory was ordered in 1951 to resume M1 production. While plans were being formulated to begin production, a number of M1s were assembled using leftover receivers in the Armory’s inventory. For example, in 1952, some rifles were put together with unused, late World War II-vintage M1 receivers that had been drilled with five holes on the left side—for the Griffin & Howe scope mount bracket—for use as “M1C” sniper rifles. World War II ended before many of these sniper rifles could be assembled, so a quantity of the modified receivers remained in storage at Springfield. The holes were plugged, and the receivers were used to assemble standard service rifles, circa 1952. Most were stamped “SA 52” on the receiver behind the rear sight (to denote “Springfield Armory” and “1952” as the year of assembly). Other non-M1C Garand receivers on hand were used during this period to assemble M1s and were also marked “SA 52” on the receiver.

New-Production Springfield Armory M1 Rifles

The last Springfield M1 rifles made during World War II were serially numbered in the 3,800,000 range. When plans were formulated for Springfield to resume production in 1951, the initial serial number range assigned to the armory began with No. 4,200,000. Even though Springfield had successfully and efficiently manufactured more than 3 million M1s during World War II—and production had ceased only six years earlier—the process of getting back into new M1 production did not go as smoothly as one might imagine. The first new production M1s came off Springfield’s assembly line in 1952.

Upon passing all requisite inspections and being accepted into service, the stocks of the new-production Springfield Armory M1 rifles were stamped on the left side with a “SA/JLG” final acceptance stamp. The “SA” indicated the manufacturer and “JLG” represented the initials of Col. James L. Guion, commanding officer of Springfield Armory from July 1950 to May 1953. The “SA/JLG” stamp was used into the 4,300,000 serial-number range, when it was replaced by the “Defense Acceptance Stamp” (“spread eagle” under three stars).

As production continued, Springfield was subsequently assigned additional blocks of serial numbers, which eventually extended into the low 6,000,000 range. As will be discussed, the assigned serial number blocks were not consecutive, as several blocks were set aside for M1 production by other contractors.

Serious shortages of certain raw materials, including suitable steel, caused vexing delays in production. For example, Springfield’s records indicate that more than 120,000 barrel blanks were rejected in early 1952 due to the use of an unsatisfactory grade of steel. To help alleviate such shortages, a contract was given to the Marlin Firearms Co. for the production of M1 rifle barrels. Springfield eventually corrected the metallurgy problems with the barrel blanks, and the use of Marlin-made barrels in new production Springfield M1 rifles was extremely short-lived.

While the basic design of the M1 rifle did not change, there were numerous minor differences between the Korean War production M1s and those made during World War II. Among the most apparent of these changes were the use of the latest pattern parts, such as the “T105E1” rear-sight assembly, and the addition of a relief cut to the operating rod. Another change was the format of the “drawing number” stamped on many of the parts, which generally had a “55” or “65” prefix added.

Additional Garand sources were sought to supplement the efforts of Springfield Armory, and inquiries were made with a number of civilian manufacturers regarding potential M1 production. Several armsmakers, including Winchester and Remington, were considered but, for various reasons, no rifle production contracts were forthcoming to either entity. Remington was awarded a contract for “pilot production” of some M1 components, but the contract was cancelled prior to completion.

There were a number of factors considered regarding potential new manufacturers of the M1 rifle. Government documents dating from the period indicate that there was a lot of unease regarding the perceived vulnerability of American armsmakers, because most were located in the New England area. This geographic concentration of manufacturers was viewed as a major concern in the newly dawning nuclear age, and it was deemed advisable to disperse some arms production to other areas of the country.

One of the first steps taken for resumption of new M1 rifle production by commercial firms was a barrel-making contract granted to the Line Material Co.of Birmingham, Ala. The barrel was correctly viewed as a critical component of the rifle, and it was expected that Line Material could provide barrels to other firms that might start in M1 production, thus expediting manufacture. Barrels made by Line Material were stamped “LMR” along with the drawing number, date of barrel production (month and year), “heat-lot” code and “P” proof-firing stamp.

International Harvester Corporation

On June 15, 1951, the International Harvester Corp. of Evansville, Ill., was granted a contract for M1 Garand production. Although a well-known maker of farm equipment and vehicles, International Harvester was perhaps an unlikely choice as a manufacturer of the nation’s standard service rifle, given the firm’s lack of prior armsmaking experience.

IHC immediately began plans for mass production. During the process, its engineering staff received much-needed assistance from the Springfield Armory and the U.S. Army Ordnance Department. One of the first decisions was to utilize the bulk of the LMR barrels for the IHC M1s. Despite these efforts, IHC’s manufacturing program was constantly plagued by a variety of problems.

By late 1952, the first rifles trickled slowly from the Evansville plant. However, it was not until the second quarter of 1953 that the company could reasonably be described as engaging in mass production of the Garand. Even after delivery began, serious problems and production delays continued. To help alleviate the on-going production difficulties, IHC acquired thousands of receivers from Springfield, although it was originally intended that the company would make its own receivers. The receivers manufactured for IHC by Springfield were marked “U.S. Rifle/Cal. .30 M1/International Harvester” but can be distinguished from the receivers actually made by IHC by the format of these markings. Also, the receivers manufactured by International Harvester were not marked with heat-lot codes like the Springfield receivers. There are four, distinct receiver-marking variants found on International Harvester M1 rifles, and IHC was assigned two blocks of serial numbers: 4,400,000 to 4,660,000 and 5,000,501 to 5,278,245.

Many of the other parts were marked with an “IHC” prefix or suffix to the component’s drawing number to identify the prime contractor. Such parts included the bolt, operating rod, trigger housing, safety, windage knob, elevating pinion, gas cylinder lock screw and hammer. The barrel channel of most International Harvester stocks was stamped with a four digit number, believed to be a julian calendar date, sometimes accompanied by a two letter prefix (“OR” or “HR”). Early production stocks had a crossed-cannons Ordnance Department escutcheon stamped on the right side, but this was soon discontinued in favor of the Defense Acceptance Stamp applied to the left side of the stock. Most of the IHC stocks were stamped with a 1/2" Defense Acceptance Stamp.

International Harvester continued to acquire certain parts from other sources, mainly Springfield Armory, in order to meet its production quotas. At various times during the course of production, Springfield continued to provide receivers to IHC as well as other components, including barrels, safeties and hammers. Therefore, a factory-original International Harvester rifle can often contain a number of “SA” marked parts.

Eventually, shrinking demand for new rifles and the recurring production difficulties motivated International Harvester to seek an early end to its M1 production program. The last rifles made by IHC were completed in January 1956, by which time the company had delivered a total of 337,623 M1s. Despite the production glitches and delays, International Harvester M1 rifles were as serviceable as those made by any other manufacturer. The limited production figures, and the number of interesting variants (including the receiver-marking variations), combine to make IHC M1s quite popular on today’s collector market.

Harrington & Richardson Arms Company

The only other prime commercial contractor for M1 rifle production in the post-World War II period was the Harrington & Richardson Arms Co. of Worcester, Mass. On April 3, 1952, H&R was given a contract for the production of 100,000 M1 rifles. A second order for 31,000 additional rifles was placed on June 25, 1952. The firm had produced a number of types of firearms for the civilian market for many years, but H&R’s prior experience in military firearm production for the government was primarily limited to the Reising .45 ACP submachine gun that it made under U.S. Marine Corps contract during World War II.

Although H&R did not receive its M1 production contract until almost a year after the International Harvester contract was granted, H&R was able to capitalize on its armsmaking experience, beginning delivery of M1 rifles at about the same time as IHC. Even so, H&R experienced its share of difficulties in getting M1 production underway. For example, on very early rifles, the company had to acquire some miscellaneous parts, such as operating rods, bolts and hammers, from Springfield. Otherwise, Harrington & Richardson M1 rifles primarily utilized “HRA”-marked parts, including barrels. H&R stocks had a noticeably different contour (especially behind the receiver) as compared to Springfield Armory and International Harvester stocks of the same vintage. Most of the H&R stocks were stamped with a 3/8" Defense Acceptance Stamp, although there were some exceptions, mainly on later rifles.

Harrington & Richardson was initially assigned two blocks of serial numbers: 4,660,001 to 4,800,000 and 5,488,247 to 5,793,847. In mid-1956, H&R manufactured an additional 400 rifles beyond this last assigned range and was given a third serial number block, 6,034,330 to 6,034,729 for those rifles.

Unlike the seemingly hodge-podge of parts found on some IHC M1 rifles, there was typically much more consistency in the H&R examples, including the format of the receiver markings. Also, unlike IHC, H&R made its own barrels for most of the company’s production run. However, when International Harvester opted out of its contact, a number of the LMR barrels on hand were diverted to H&R and used to assemble some late-production rifles.

Some collectors consider H&R M1 rifles to be among the best regarding fit, finish and overall craftsmanship. Production of the H&R M1 rifles ceased in May 1956, by which time 428,600 rifles had been delivered.

It is doubtful if any of the IHC or H&R M1 rifles made it overseas prior to the cessation of active combat operations of the Korean War in 1953. By the time these two contractors were able to get into mass production, the pressing need for new M1s had passed, and the majority of the rifles remained stateside or were used to fulfill various military foreign-aid commitments.

Post-World War II Garand Sniper Rifles

World War II ended with the M1C as the standardized American sniper rifle, although few were actually fielded before V-J Day. The M1D sniper rifle was also standardized during this period, but except for a handful assembled for evaluation, this variant was not put into production. Unlike the M1C, which required holes to be drilled in the receiver, the M1D permitted standard service rifles to be converted to sniper configuration by the simple expedient of installing the special barrel (with integral scope mount) and a shortened rear handguard.

The supply of M1C rifles was sufficient to meet demand until 1950, when Springfield Armory was ordered to convert a number of standard M1s to M1C configuration. But it was determined that a better course of action would be to concentrate on the M1D variant instead, which would permit a larger number of sniper rifles to be produced in a shorter period of time. Springfield Armory produced a relatively large number of M1D barrels during the 1951 to 1953 period. Many of these were fitted to existing receivers, but a quantity of extra barrels was also manufactured at this time for potential future use. These “surplus” M1D barrels were utilized into the late 1960s by several arsenal facilities for conversion of M1 rifles to M1D sniper rifles. Unlike the World War II M1C sniper rifles, there were no new production M1D rifles ever produced, as all were converted from existing M1 service rifles.

Few, if any, M1D sniper rifles were used in the Korean War, although a number of World War II-production M1C sniper rifles were. The M1D remained in the U.S. Army’s inventory well after the Vietnam War, and some are reported to still be in National Guard armories today.

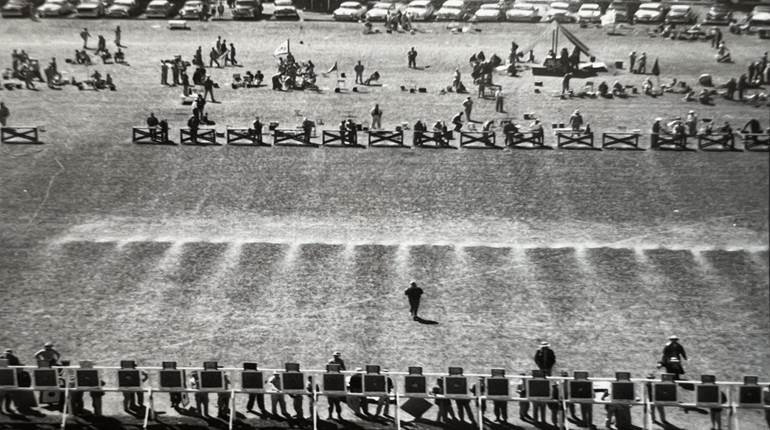

National Match M1 Rifles

In March 1953, the Springfield Armory was ordered by the Ordnance Department to produce 800 M1 rifles for the National Matches at Camp Perry, Ohio. This directive marked the first time since the late 1930s that new orders for National Match rifles were placed. Of course, by this time, the M1 had replaced the M1903A1 as the platform for the National Match rifle. Unlike later variants of National Match M1 rifles, the first M1 National Match rifles, termed “Type 1” by today’s collectors, were essentially little more than finely tuned service rifles. The only apparent National Match feature was the “NM” marking on the barrel. Serial numbers began in the 5,800,000 range, and barrel dates were between 1953 and 1956. During the course of the M1 National Match rifle’s tenure of service, specialized parts (some “NM” marked) including the “hooded” rear-sight apertures and glass-bedded stocks began to appear. A few years later, Springfield utilized existing overhauled receivers rather than new-production receivers to assemble National Match M1s. The last Springfield Armory-made National Match M1 rifles were turned out in 1963. Like the M1D sniper rifle, it is usually not possible to ascertain if a particular M1 rifle is a genuine National Match rifle without accompanying government documentation.

Cessation Of Service-Rifle Production

Springfield Armory

Springfield continued to produce M1 service rifles and National Match Rifles after the International Harvester and Harrington & Richardson contracts were completed. By mid-1956, plans were formulated for Springfield Armory to begin phasing out M1 manufacture. The barrel-production line was shut down in October 1956, and the final batch of receivers was finished in December. Some rifles continued to be assembled from parts on hand for the next few months.

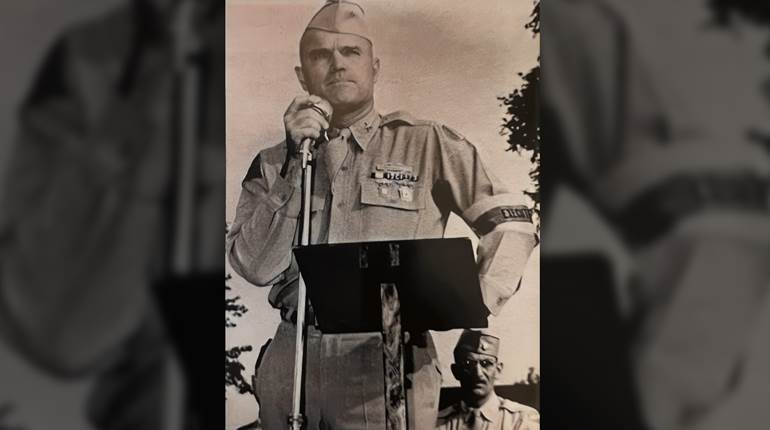

The last “production” M1 rifle, serial number 6,084,405, was completed on May 17, 1957 and was accompanied by much fanfare—including an appearance by John C. Garand at the ceremony. Interestingly, M1 rifles with higher serial numbers have been noted. This apparent anomaly can be explained because, contrary to what many people may believe, most military arms, including M1 rifles, were not assembled in sequential serial-number order. Secondly, some of the National Match M1s continued to be assembled after service rifle production ceased, and may have used higher-numbered receivers. The highest M1 serial number reported in government documents is 6,090,905.

From the commencement of new production in 1952 until the cessation of manufacture, Springfield Armory completed 661,747 M1 rifles, including National Match variants. As is the case with all M1s, most of these rifles have been arsenal-overhauled one or more times over the years, and relatively few remain in their original factory configuration today.

The adoption of the M14 in 1957 marked an end to the M1 as the standardized American military service rifle, but it didn’t mark an end to its tenure of service. Many M1 rifles remained in the military’s inventory for a number of years afterward. Large quantities were sent to a number of our present and erstwhile allies under various military-assistance programs, including South Korea, South Vietnam, Turkey, Iran, Denmark, Greece and several Central and South American countries (to name just a few). For more than a decade, the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP), successor to the venerable Director of Civilian Marksmanship (DCM), has sold several types of U.S. military arms, including M1 rifles, to qualified purchasers. Many of these were post-World War II M1 rifles, ranging in condition from worn but serviceable to “new in the factory wrap.” The CMP M1 rifle sales program is still active today.

The number of interesting variations and the availability of the rifles (thanks in large measure to the CMP), has resulted in the post-World War II M1s becoming increasingly popular with collectors. The desirability of M1s made by Springfield Armory, International Harvester and Harrington & Richardson in the early- to mid-1950s are beginning to rival some of the World War II-era Garands made by Springfield and Winchester.

While the M1 was the quintessential American military rifle of World War II, its place in the post-war military arsenal should never be overlooked.